Did you know that your genetic variants can impact how well you respond to acupuncture? Join me in learning about the fascinating science behind how acupuncture works, the genetic ties, and possible ways to increase acupuncture efficacy.

Acupuncture: How it works, genetic variations, and clinical trial data

Acupuncture originated in China over 2,500 years ago and became popular in the US around four decades ago. Research shows that inserting acupuncture needles into specific points stimulates the nervous system, reducing pain and helping heal certain issues.

Acupuncture can be used to treat:

- digestive disorders

- respiratory disorder

- neurological issues

- pain

- urinary disorders, and more

How does acupuncture work?

Acupuncture involves inserting a needle (or putting pressure or electrical current) on specific points on the body. The needle is then manipulated or rotated around at that point.

There is a lot of research into how and why acupuncture works for many people with many different disorders. On its surface, it seems pretty odd that sticking a needle into specific locations on the body would take away the pain or cure a neurological issue.

Sure, it has worked in Chinese medicine for a very long time, but why? I’m not going to try to explain the traditional Chinese thoughts on Qi or energy flow because I am sure to get it wrong. Instead, I will highlight recent research that has pointed to some fascinating physiology at the traditional acupuncture points.

The Chinese discovered acupuncture points a millennia ago. More recently, modern neuroimaging techniques show us what is happening in those acupoints.

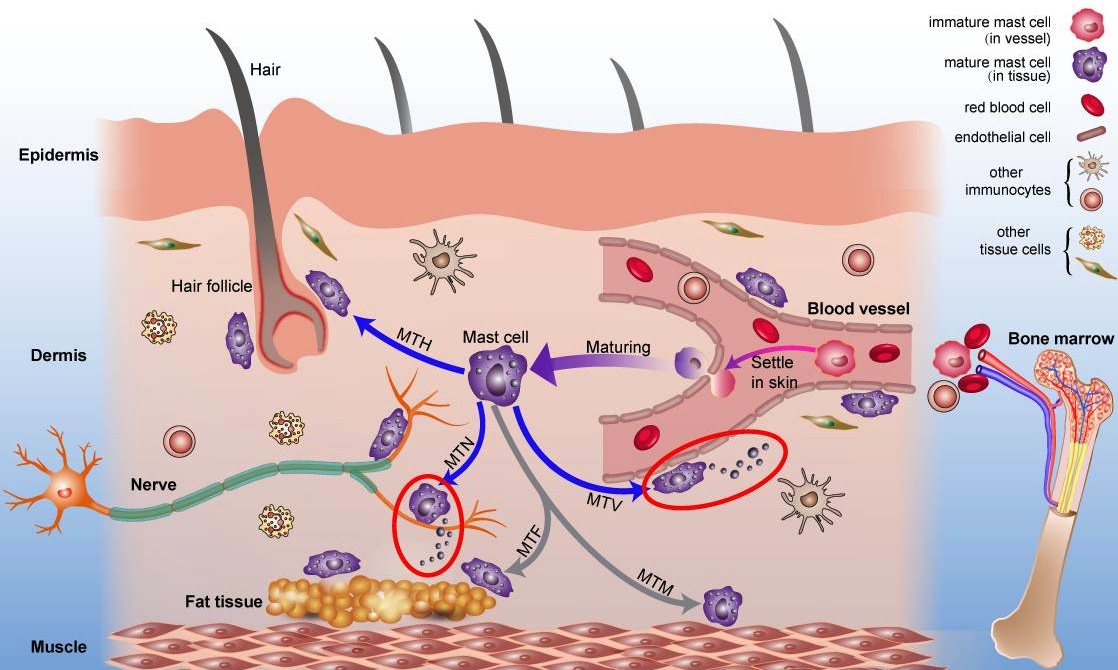

Primarily, acupuncture points are areas with lots of free nerve endings, mast cells, nearby blood vessels, and lymphatic tissue.

Mast cells surround acupuncture points:

Mast cells are a type of immune cell traditionally known for their role in allergic reactions. They cause the histamine release and allergic reactions you get when exposed to an allergen. More recent research shows that mast cells are a big part of the adaptive and innate immune response.

Acupuncture points are enriched in mast cells. Additionally, mast cells migrate and aggregate in response to acupuncture stimuli. Some researchers believe that mechanical stimulation of the mast cells, resulting in localized mast cell degranulation, is the key to how acupuncture works.

Essentially, mechanical stimulation can cause mast cells to degranulate. This degranulation causes a cascade of reactions in the spot that has been activated with the needle, initially causing a bit of swelling, itching, or slight pain. The degranulating mast cells release histamine, serotonin, ATP, and other inflammatory substances. It causes the dilation of nearby small blood vessels and the contraction of smooth muscle cells. Then there is a homeostatic regulation of that spot that causes a return to normal.[ref][ref]

How do we know it is the mast cells and not something else? Animal studies show that inhibiting mast cell degranulation stops the analgesic effect of acupuncture.[ref]

Moreover, after acupuncture needling, biopsy staining shows increased mast cells in the acupuncture point. More mast cells have been recruited to the area and are ready for subsequent activation.[ref]

Here is a diagram showing the locations of mast cells in the layers of skin cells, with the mast cells congregating around hair follicles, nerve endings, and blood vessels. CC image from PMC8909752.

Mast cells and mechanosensitive channels:

Mast cells have specific receptors on them that can detect physical stimulation.

For example, vibratory urticaria is the itching and hives associated with vibrations, which is caused by vibrations triggering mast cell degranulation.[ref] (I get this when riding my bike down a bumpy gravel road for a few miles — itchy blotches inevitably pop up on my arms.)

Stimulating mast cells causes the release of chemicals that regulate nerve activity as well as increase the permeability of small blood vessels. For example, releasing histamine dilates blood vessels, allowing for the flow of inflammatory cytokines that can recruit immune cells that cause a small, localized inflammatory response.[ref]

Mechanical stimulation involves inserting a needle and swishing it around (probably not the proper term :-) releases calcium and activates the receptors on the mast cells.

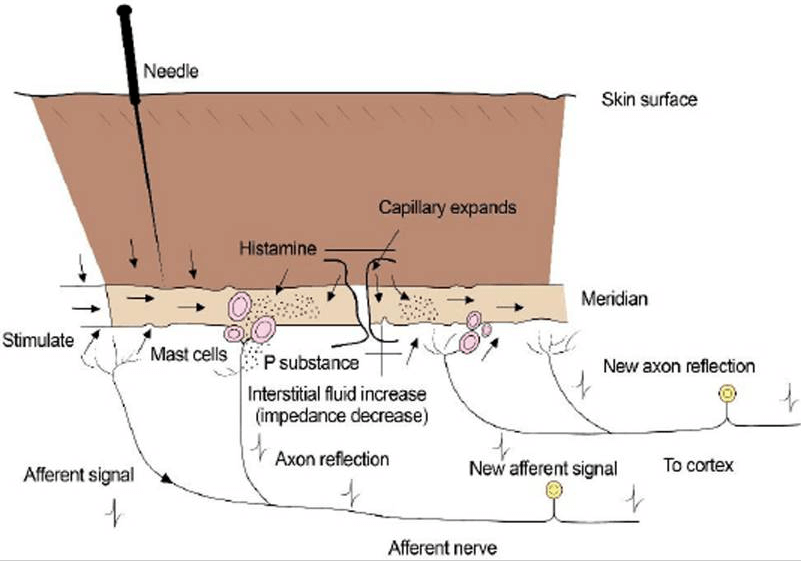

Let’s dig into this further and look at how this ties into the small nerves that terminate in the acupuncture points.

TRPV1 and TRPV2 channel activation

TRPV1 (Transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1) receptors are cation channels prevalent on the small C fiber nerves. The TRPV1 receptors are activated by various substances and trigger a nerve response. Additionally, TRPV1 channels are essential in the regulation of body temperature.

TRPV1 receptors are activated by temperatures greater than 43 °C (109 °F), acids, capsaicin (hot peppers), wasabi, anandamide, bradykinin, histamine, and lipoxygenase metabolites.[ref] Menthol, found in peppermint, is an inhibitor of TRPV1, as is cold temperature.

TRPV2 is similar to TRPV1 receptors, with a few differences. It is not responsive to capsaicin but is activated at temperatures higher than 52 °C and by pressure or mechanical stimulation. It is also activated by several hormones, swelling, stretching, and cannabinoids.[ref]

TRPV1 and TRPV2 are also found on the surface of mast cells. Physical stimulus from the needle can activate the receptors and cause mast cell degranulation. When stimulated, mast cells release various chemicals, including histamine, which activates the TRPV1 channels on small nerve fibers. Histamine also nearby causes capillaries to dilate.[ref]

TRPV1 channels are increased in nerve fibers after being stimulated with electroacupuncture. Researchers find that nitric oxide synthase and TRPV1 expression are both increased and may play a vital role in the transduction of the signal from electroacupuncture to the central nervous system.[ref]

Here is an open-source diagram of what is thought to be going on with the mechanical stimulation from the acupuncture needle. CC image from PMC8288732/

What happens after an acupuncture point is triggered?

Needling causes mast cells to release vasoactive substances, including histamine. The vasodilation increases blood flow to the acupuncture point, bringing in oxygen and immune system cells. Additionally, mast cells release serotonin and other substances that activate and stimulate nerve function.[ref]

Initially, the acupuncture needle may cause a little redness, swelling, or itching immediately after treatment.

As mentioned above, acupuncture stimulates a specific type of sensory nerve. There are a couple of ways to define nerves in the body:

- Afferent nerves are sensory fibers that send signals to the brain, such as pain or sensation.

- Efferent nerves relay signals from the brain or central nervous system to the periphery – such as signaling for a muscle to move.

There are four types of afferent nerve fibers, and the Aδ and C small nerve fibers are the ones that transmit pain. Acupuncture stimulates Aδ and C fibers.[ref] (read more about these small nerve fibers in my article on small fiber neuropathy)

The needle immediately stimulates the nerve endings in the acupoints. Increased mechanical stimulation then reduces the activation threshold of the nerve, allowing it to fire more easily. Researchers theorize this change in activation threshold results in increased nerve plasticity and nerve function at the nociceptor at the end of the nerve.

Additionally, the mast cell activation and the small nerve endings recruit immune cells, such as macrophages, to the area. This small spot of neuroinflammation then promotes a homeostatic healing response.[ref] Researchers find that the slight increase in inflammation triggers anti-inflammatory IL-10 to increase in the area along the nerve.[ref]

In my mind, this is similar to how stressing out your muscles with some weight lifting ends up being beneficial. Researchers point out that we (and animals) naturally rub, massage, scratch at, or lick spots that hurt, and these areas often correspond to acupoints.

When all goes well, tissue damage and the inflammatory response heal quickly through an active process termed the resolution of inflammation. Over the past decade, researchers have found that the resolution of inflammation is an important, active process that stops inflammation and facilitates healing by recruiting stem cells and other mediators. (Read more about how the resolution of inflammation is supposed to work.)

Research studies on acupuncture effectiveness:

If you’re like me, you may wonder if clinical trials show that acupuncture actually works. Hundreds of trials show that it is effective for many, but not all, conditions. Here are just a few examples:

- A meta-analysis found that acupuncture may help decrease post-partum depression.[ref]

- Clinical trials of acupuncture for acne find that it doesn’t cure acne for everyone, but it statistically increases the odds of a cure.[ref]

- A meta-analysis of 18 studies found that acupuncture improves nerve conduction and symptoms in diabetic peripheral neuropathy.[ref]

- Acupuncture is generally beneficial for pain reduction after abdominal, spinal, or gynecological surgery.[ref]

- For people with dementia, acupuncture or acupressure effectively decreases agitation, anxiety, depression, and neuropsychological disturbances.[ref]

- In veterinary medicine, acupuncture is effective for pain management in pets.[ref]

- Animal studies show that acupuncture effectively increases the pain threshold in arthritis.[ref]

- For lower back pain, a randomized controlled clinical trial compared acupuncture to a sham treatment (guide tube with no needle). The acupuncture group showed statistically better improvement compared to the sham group.[ref] A cross-over trial showed similar short-term efficacy of acupuncture for lower back pain.[ref]

Not all acupuncture studies show positive results. A meta-analysis found no statistical benefit for acupuncture in IVF birth rates.[ref] Additionally, many studies only show a small (yet statistically significant) benefit. So the cost-benefit ratio may not always make acupuncture the best choice.

Acupuncture Genotype Report

Not a member? Join here. Membership lets you see your data right in each article and also gives you access to the member’s only information in the Lifehacks sections.

Not everyone has a satisfactory response to acupuncture. Animal studies show that the response to acupuncture is somewhat dependent on genetics.[ref] The genetic variants below involve the TRPV1 receptor, immune function, and response to pain. They have been linked to acupuncture response in various studies.

Keep in mind that most of these studies have somewhat small numbers of participants, and most of the studies aren’t replicated. In other words, these variants may explain individual differences in response to acupuncture, but this is likely not the whole picture.

TRPV1 gene: encodes the receptor for heat, pain, capsaicin

Check your genetic data for rs8065080 (23andMe v5; AncestryDNA):

- T/T: typical receptor function; acupuncture more likely to work[ref]

- C/T: typical receptor function

- C/C: higher pain tolerance to cold, heat[ref] less TRPV1 receptor activation[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs8065080 is —.

NFKB2 gene: encodes a transcription factor that responds to inflammatory cytokines in regulating the immune response to infections.

Check your genetic data for rs1056890 (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: more likely to respond to acupuncture (common genotype)[ref]

- A/G: not as likely to respond to acupuncture

- A/A: not as likely to respond to acupuncture

Members: Your genotype for rs1056890 is —.

TCL1A gene: involved in the development of mature T cells

Check your genetic data for rs2369049 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: more likely to respond to acupuncture[ref]

- A/G: more likely to respond to acupuncture

- A/A: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs2369049 is —.

COMT gene: encodes an enzyme that breaks down catechol neurotransmitters and interacts with your perception of pain (Read more about COMT)

Check your genetic data for rs4680 Val158Met (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: higher COMT activity (often called fast COMT or Val/Val)

- A/G: intermediate COMT activity (most common genotype); somewhat more likely to respond to acupuncture; acupuncture induced decreased default mode network connectivity in the brain.[ref]

- A/A: 40% lower COMT activity (often called slow COMT or Met/Met); more likely to respond to acupuncture[ref][ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs4680 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs6269 (23andMe v4, v5):

- A/A: typical

- A/G: more likely to respond to acupuncture for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors[ref]

- G/G: no statistical effect on acupuncture

Members: Your genotype for rs6269 is —.

DRD2 gene: dopamine receptor

Check your genetic data for rs1800497 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: reduced dopamine binding, likely less response to acupuncture for smoking cessation

- A/G: more likely to respond to acupuncture for smoking cessation

- G/G: more likely to respond to acupuncture for smoking cessation[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs1800497 is —.

Lifehacks:

First, let me encourage you to do your due diligence before going to an acupuncture clinic. From speaking with people well-versed in the topic, the quality of training really matters in acupuncture. Find out the acupuncturist’s training, check reviews, and talk with clients if possible. Of course, you want a clinic with an excellent reputation for safety and cleanliness.

The rest of this article is for Genetic Lifehacks members only. Consider joining today to see the rest of this article.

Related Articles and Genes:

Brain Fog: Causes, genetics, and solutions

Explore brain fog in detail, looking at the physiological causes, genetic susceptibility, and personalized solutions.

Ashwagandha: Research-backed benefits and side effects

Are there benefits to taking ashwagandha? Learn more about this supplement and where the newest clinical research shows promise and results.

Will statins give you muscle pain? What your genes can tell you

Statins are one of the most prescribed medications in the world. One side effect of statins is myopathy, or muscle pain and weakness. Your genetic variants are significant in whether you are likely to have side effects from statins.

Back Pain and Your Genes

For some people, back pain is a daily occurrence that drastically affects their quality of life. For others, it may be an intermittent nagging problem, often without rhyme or reason. Your genes play a role in whether disc degeneration gives you back pain.

References:

Abraham, Therese S., et al. “TRPV1 Expression in Acupuncture Points: Response to Electroacupuncture Stimulation.” Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, vol. 41, no. 3, Apr. 2011, pp. 129–36. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.01.001.

Binder, Andreas, et al. “Transient Receptor Potential Channel Polymorphisms Are Associated with the Somatosensory Function in Neuropathic Pain Patients.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 3, Mar. 2011, p. e17387. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017387.

Boyden, Steven E., et al. “Vibratory Urticaria Associated with a Missense Variant in ADGRE2.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 374, no. 7, Feb. 2016, pp. 656–63. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1500611.

“Can Acupressure Help With Weight Loss?” Verywell Health, https://www.verywellhealth.com/acupressure-weight-loss-5115110. Accessed 11 July 2022.

Cao, Hui-Juan, et al. “Acupoint Stimulation for Acne: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Medical Acupuncture, vol. 25, no. 3, June 2013, pp. 173–94. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2012.0906.

Deering-Rice, Cassandra E., et al. “Characterization of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) Variant Activation by Coal Fly Ash Particles and Associations with Altered Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin-1 (TRPA1) Expression and Asthma.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 291, no. 48, Nov. 2016, pp. 24866–79. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.746156.

Dewey, Curtis Wells, and Huisheng Xie. “The Scientific Basis of Acupuncture for Veterinary Pain Management: A Review Based on Relevant Literature from the Last Two Decades.” Open Veterinary Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, 2021, pp. 203–09. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5455/OVJ.2021.v11.i2.3.

Dhakal, Subash, and Youngseok Lee. “Transient Receptor Potential Channels and Metabolism.” Molecules and Cells, vol. 42, no. 8, Aug. 2019, pp. 569–78. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.14348/molcells.2019.0007.

Genovese, Timothy J., et al. “Genetic Predictors of Response to Acupuncture or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Cancer Survivors: An Exploratory Analysis.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, vol. 62, no. 3, Sept. 2021, pp. e192–99. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.03.002.

Genovese, Timothy J., and Jun J. Mao. “Genetic Predictors of Response to Acupuncture for Aromatase Inhibitor–Associated Arthralgia Among Breast Cancer Survivors.” Pain Medicine: The Official Journal of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 191–94. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny067.

Harris, Melissa L., et al. “Acupuncture and Acupressure for Dementia Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms: A Scoping Review.” Western Journal of Nursing Research, vol. 42, no. 10, Oct. 2020, pp. 867–80. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945919890552.

Inoue, Motohiro, et al. “Relief of Low Back Pain Immediately after Acupuncture Treatment–a Randomised, Placebo Controlled Trial.” Acupuncture in Medicine: Journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society, vol. 24, no. 3, Sept. 2006, pp. 103–08. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/aim.24.3.103.

Itoh, Kazunori, et al. “Effects of Trigger Point Acupuncture on Chronic Low Back Pain in Elderly Patients–a Sham-Controlled Randomised Trial.” Acupuncture in Medicine: Journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society, vol. 24, no. 1, Mar. 2006, pp. 5–12. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/aim.24.1.5.

Li, Wei, et al. “Effectiveness of Acupuncture Used for the Management of Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2019, Mar. 2019, p. 6597503. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6597503.

Li, Yingchen, et al. “Mast Cells and Acupuncture Analgesia.” Cells, vol. 11, no. 5, Mar. 2022, p. 860. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11050860.

Lim, Tiaw-Kee, et al. “Acupuncture and Neural Mechanism in the Management of Low Back Pain—An Update.” Medicines, vol. 5, no. 3, June 2018, p. 63. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines5030063.

Mingfu, Luo, et al. “Study on the Dynamic Compound Structure Composed of Mast Cells, Blood Vessels, and Nerves in Rat Acupoint.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : ECAM, vol. 2013, 2013, p. 160651. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/160651.

Park, Hi-Joon, et al. “The Association between the DRD2 TaqI A Polymorphism and Smoking Cessation in Response to Acupuncture in Koreans.” Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.), vol. 11, no. 3, June 2005, pp. 401–05. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2005.11.401.

Romero, Sally A. D., et al. “Genetic Predictors to Acupuncture Response for Hot Flashes: An Exploratory Study of Breast Cancer Survivors.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.), vol. 27, no. 8, Aug. 2020, pp. 913–17. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001545.

Shah, Shivani, et al. “Acupuncture and Postoperative Pain Reduction.” Current Pain and Headache Reports, vol. 26, no. 6, June 2022, pp. 453–58. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-022-01048-4.

Suh, Young-Ger, and Uhtaek Oh. “Activation and Activators of TRPV1 and Their Pharmaceutical Implication.” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 11, no. 21, 2005, pp. 2687–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612054546789.

Waits, Alexander, et al. “Acupressure Effect on Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 37, Feb. 2018, pp. 24–34. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.12.004.

Wan, You, et al. “The Effect of Genotype on Sensitivity to Electroacupuncture Analgesia.” Pain, vol. 91, no. 1, Mar. 2001, pp. 5–13. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00416-4.

Wang, Guangjun, et al. “Acupoint Activation: Response in Microcirculation and the Role of Mast Cells.” Medicines, vol. 1, no. 1, Nov. 2014, pp. 56–63. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines1010056.

Wang, Li-Na, et al. “Activation of Subcutaneous Mast Cells in Acupuncture Points Triggers Analgesia.” Cells, vol. 11, no. 5, Feb. 2022, p. 809. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11050809.

Wang, Lina, et al. “TRPV Channels in Mast Cells as a Target for Low-Level-Laser Therapy.” Cells, vol. 3, no. 3, June 2014, pp. 662–73. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells3030662.

Yang, Xuejuan, et al. “Effect of Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Val158Met Polymorphism on Resting-State Brain Default Mode Network after Acupuncture Stimulation.” Brain Imaging and Behavior, vol. 12, no. 3, June 2018, pp. 798–805. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-017-9735-6.

Yiu, Edwin ML, et al. “Wound Healing Effect of Acupuncture for Treating Phonotraumatic Vocal Pathologies: Cytokine Study.” The Laryngoscope, vol. 126, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. E18–22. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25483.

Yu, Bin, et al. “Acupuncture Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews.” Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, vol. 46, no. 3, June 2021, pp. 585–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13351.