Key takeaways:

~Everyone is exposed to viruses that cause respiratory illness, but not everyone develops symptoms.

~ There are research-backed ways to both prevent colds and respiratory illnesses and reduce symptoms when you do get sick.

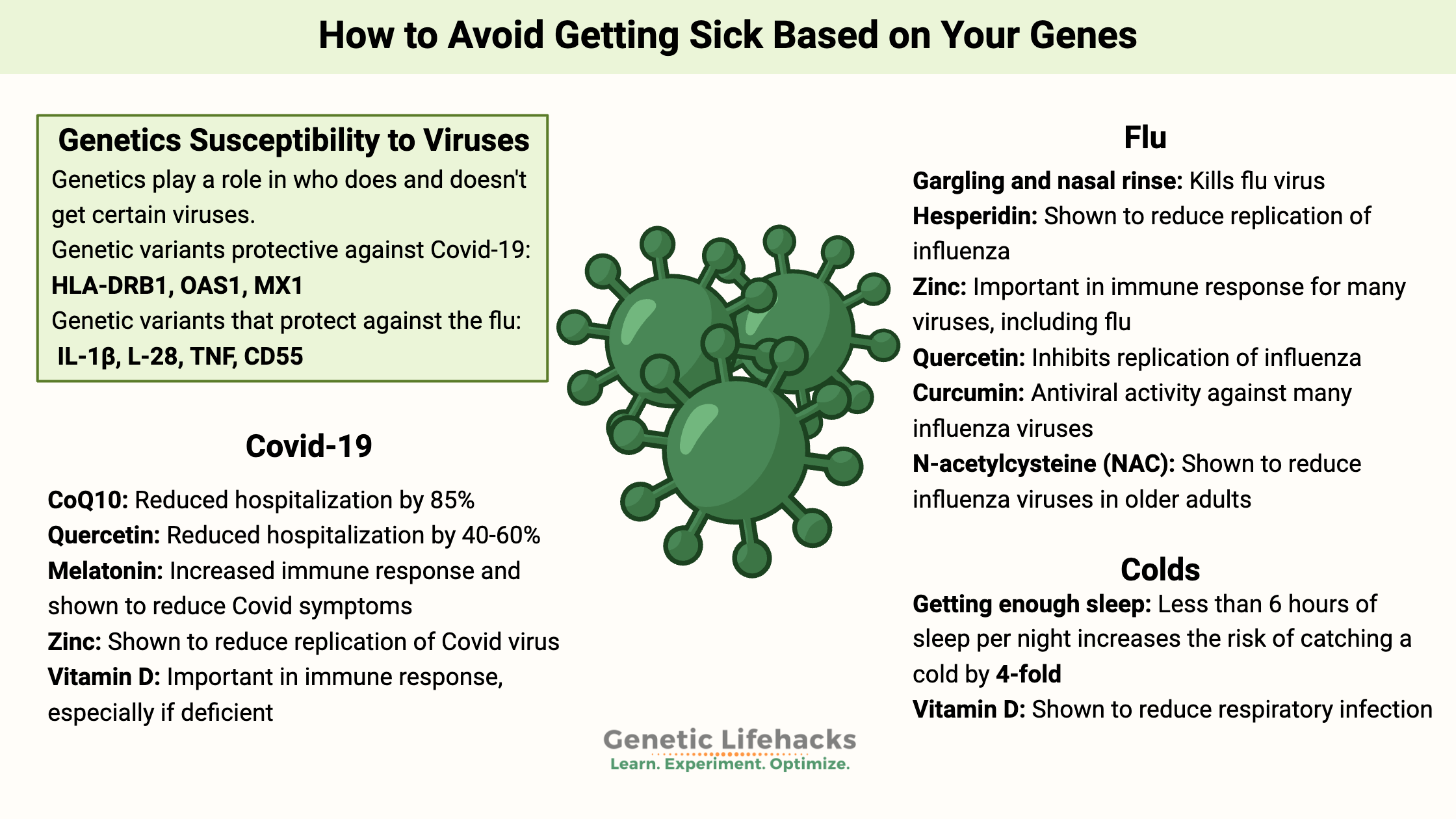

~ Genetic variants strongly affect whether you are likely to get sick from certain viruses. Knowing this can help you prioritize your avoidance measures.

~ Be prepared during cold and flu season with supplies on hand for combating illness.

Staying Well During Virus Season:

No one enjoys getting sick—time off work, feeling terrible, and being confined to the couch with a box of tissues. It stinks! When my kids were little and got sick, a trip to the doctor would inevitably result in the doctor saying, “It’s just a virus”. The meaning was clear: nothing to be done; viruses can’t be treated or prevented; your child will feel better in a few days.

This mindset that there is nothing to be done about viruses continued, at least for me, until recently. My thoughts were that everyone catches a cold or “the crud” every year or two, usually in December or January, and that some people were lucky and didn’t get exposed to it.

But I was wrong. It turns out that there is a lot you can do to help your immune system avoid illnesses, and there are genetic reasons that some people won’t become ill from specific viruses.

Let’s dive into the research on how to minimize your risk of getting sick.

Viruses are everywhere, including your nose.

How many viral infections per year?

A 2015 study looked at how many respiratory viruses were found in Utah families. For an entire year, researchers swabbed noses and asked about symptoms weekly in 26 households (108 people). The results showed that 783 viral episodes were detected over the year, with less than half of the viral episodes causing any symptoms. Viruses were detected in a quarter of the weekly samples, and almost everyone had a rhinovirus detection at some point during the year.[ref]

The most common viruses causing symptoms were coronaviruses, human metapneumovirus, and influenza A. Bocavirus and rhinovirus detections were usually asymptomatic. Households with many young children had more viral infections.

The study concluded that adolescents and adults had an average of 5 viral respiratory illnesses per year, but that most were asymptomatic. Children under the age of 5 were much more likely to have respiratory symptoms.

Immune system:

Once you’ve been exposed to a specific virus, your immune system makes antibodies that will recognize and quickly fight off the virus when you are exposed again the next year. This is why kids are more likely to have symptoms of a viral infection than adults.

Genetics:

Not everyone is equally susceptible to every virus. Some people have genetic factors that bolster their defenses against certain viral infections. Check out the full article on susceptibility to viral illnesses to see where your superpowers lie.

Prevention and Treatment Strategies for Flu, Cold, and Common Cold:

Let me be clear: I’m not saying that any of the following are miracle pills that will prevent all illnesses for everyone. Instead, I want everyone to take away from this article the research-backed ideas for preventing the common respiratory illnesses that circulate every year. You may still get sick, but knowing what works and being prepared can help lessen the symptoms and duration.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

References:

Abuelgasim, Hibatullah, et al. “Effectiveness of Honey for Symptomatic Relief in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, vol. 26, no. 2, Apr. 2021, pp. 57–64. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111336.

Alam, Mohammad Shah, et al. “N-Acetylcysteine Reduces Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Advanced Veterinary and Animal Research, vol. 10, no. 2, June 2023, pp. 157–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5455/javar.2023.j665.

Ameri, Ali, et al. “Efficacy and Safety of Oral Melatonin in Patients with Severe COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Inflammopharmacology, vol. 31, no. 1, Feb. 2023, pp. 265–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-022-01096-7.

Asl, Sima Heydarzadeh, et al. “Immunopharmacological Perspective on Zinc in SARS-CoV-2 Infection.” International Immunopharmacology, vol. 96, July 2021, p. 107630. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107630.

Bicer, Suat, et al. “Virological and Clinical Characterizations of Respiratory Infections in Hospitalized Children.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 39, Mar. 2013, p. 22. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-39-22.

Bishayi, Biswadev, et al. “Beneficial Effects of Exogenous Melatonin in Acute Staphylococcus Aureus and Escherichia Coli Infection-Induced Inflammation and Associated Behavioral Response in Mice After Exposure to Short Photoperiod.” Inflammation, vol. 39, no. 6, Dec. 2016, pp. 2072–93. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-016-0445-9.

Boga, Jose Antonio, et al. “Beneficial Actions of Melatonin in the Management of Viral Infections: A New Use for This ‘Molecular Handyman’?” Reviews in Medical Virology, vol. 22, no. 5, Sept. 2012, pp. 323–38. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.1714.

Byington, Carrie L., et al. “Community Surveillance of Respiratory Viruses Among Families in the Utah Better Identification of Germs-Longitudinal Viral Epidemiology (BIG-LoVE) Study.” Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, vol. 61, no. 8, Oct. 2015, pp. 1217–24. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ486.

Cheema, Huzaifa Ahmad, et al. “Quercetin for the Treatment of COVID‐19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis.” Reviews in Medical Virology, vol. 33, no. 2, Mar. 2023, p. e2427. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2427.

Di Pierro, Francesco, Somia Iqtadar, et al. “Potential Clinical Benefits of Quercetin in the Early Stage of COVID-19: Results of a Second, Pilot, Randomized, Controlled and Open-Label Clinical Trial.” International Journal of General Medicine, vol. 14, 2021, pp. 2807–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S318949.

Di Pierro, Francesco, Amjad Khan, et al. “Quercetin as a Possible Complementary Agent for Early-Stage COVID-19: Concluding Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 13, Jan. 2023. Frontiers, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1096853.

Ebrahimi, Tayebe, et al. “Effectiveness of Mouthwashes on Reducing SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Oral Health, vol. 23, no. 1, July 2023, p. 443. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03126-4.

Fogleman, Corey, et al. “A Pilot of a Randomized Control Trial of Melatonin and Vitamin C for Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19.” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM, vol. 35, no. 4, 2022, pp. 695–707. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2022.04.210529.

Guenezan, Jeremy, et al. “Povidone Iodine Mouthwash, Gargle, and Nasal Spray to Reduce Nasopharyngeal Viral Load in Patients With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, vol. 147, no. 4, Apr. 2021, pp. 400–01. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.5490.

Huang, Sheng-Hai, et al. “Inhibitory Effect of Melatonin on Lung Oxidative Stress Induced by Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Mice.” Journal of Pineal Research, vol. 48, no. 2, Mar. 2010, pp. 109–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00733.x.

Huijghebaert, Suzy, et al. “Saline Nasal Irrigation and Gargling in COVID-19: A Multidisciplinary Review of Effects on Viral Load, Mucosal Dynamics, and Patient Outcomes.” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 11, June 2023, p. 1161881. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1161881.

Jolliffe, David A., et al. “Effect of a Test-and-Treat Approach to Vitamin D Supplementation on Risk of All Cause Acute Respiratory Tract Infection and Covid-19: Phase 3 Randomised Controlled Trial (CORONAVIT).” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), vol. 378, Sept. 2022, p. e071230. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071230.

Kim, Tae Kyung, et al. “Vitamin C Supplementation Reduces the Odds of Developing a Common Cold in Republic of Korea Army Recruits: Randomised Controlled Trial.” BMJ Military Health, vol. 168, no. 2, Apr. 2022, pp. 117–23. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2019-001384.

Krawitz, Christian, et al. “Inhibitory Activity of a Standardized Elderberry Liquid Extract against Clinically-Relevant Human Respiratory Bacterial Pathogens and Influenza A and B Viruses.” BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 11, Feb. 2011, p. 16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-11-16.

Mehrbod, Parvaneh, et al. “Quercetin as a Natural Therapeutic Candidate for the Treatment of Influenza Virus.” Biomolecules, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2020, p. 10. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11010010.

Meister, Toni Luise, et al. “Virucidal Efficacy of Different Oral Rinses Against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa471. Accessed 27 Aug. 2024.

Mocchegiani, Eugenio, et al. “Zinc: Dietary Intake and Impact of Supplementation on Immune Function in Elderly.” Age, vol. 35, no. 3, June 2013, pp. 839–60. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-011-9377-3.

Oduwole, Olabisi, et al. “Honey for Acute Cough in Children.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 4, no. 4, Apr. 2018, p. CD007094. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007094.pub5.

Parisi, Giuseppe Fabio, et al. “Nutraceuticals in the Prevention of Viral Infections, Including COVID-19, among the Pediatric Population: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 5, Feb. 2021, p. 2465. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052465.

Paul, Ian M., et al. “Effect of Honey, Dextromethorphan, and No Treatment on Nocturnal Cough and Sleep Quality for Coughing Children and Their Parents.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 161, no. 12, Dec. 2007, pp. 1140–46. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1140.

Prather, Aric A., et al. “Behaviorally Assessed Sleep and Susceptibility to the Common Cold.” Sleep, vol. 38, no. 9, Sept. 2015, pp. 1353–59. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4968.

Preez, Heidi N. du, et al. “N-Acetylcysteine and Other Sulfur-Donors as a Preventative and Adjunct Therapy for COVID-19.” Advances in Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 2022, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4555490.

Ramalingam, Sandeep, et al. “A Pilot, Open Labelled, Randomised Controlled Trial of Hypertonic Saline Nasal Irrigation and Gargling for the Common Cold.” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, Jan. 2019, p. 1015. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37703-3.

Reiter, Russel J., et al. “Melatonin: Highlighting Its Use as a Potential Treatment for SARS-CoV-2 Infection.” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, vol. 79, no. 3, Feb. 2022, p. 143. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-021-04102-3.

Sadeghsoltani, Fatemeh, et al. “Zinc and Respiratory Viral Infections: Important Trace Element in Anti-Viral Response and Immune Regulation.” Biological Trace Element Research, vol. 200, no. 6, 2022, pp. 2556–71. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-02859-z.

Shimizu, Y., et al. “Intake of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Reduces Duration and Severity of Upper Respiratory Tract Infection: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel Group Comparison Study.” The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, vol. 22, no. 4, 2018, pp. 491–500. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-017-0952-x.

Silvestri, Michela, and Giovanni A Rossi. “Melatonin: Its Possible Role in the Management of Viral Infections-a Brief Review.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 39, Oct. 2013, p. 61. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-39-61.

Silvestri, Michela, and Giovanni A. Rossi. “Melatonin: Its Possible Role in the Management of Viral Infections-a Brief Review.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 39, no. 1, Oct. 2013, p. 61. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-39-61.

Swaminathan, Kavya, et al. “Binding of a Natural Anthocyanin Inhibitor to Influenza Neuraminidase by Mass Spectrometry.” Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, vol. 405, no. 20, Aug. 2013, pp. 6563–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-013-7068-x.

Uraguchi, Kensuke, et al. “Association between Handwashing and Gargling Education for Children and Prevention of Respiratory Tract Infections: A Longitudinal Japanese Children Population-Based Study.” European Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 182, no. 9, Sept. 2023, pp. 4037–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05062-5.

Vorilhon, Philippe, et al. “Efficacy of Vitamin C for the Prevention and Treatment of Upper Respiratory Tract Infection. A Meta-Analysis in Children.” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 75, no. 3, Mar. 2019, pp. 303–11. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2601-7.

Zhou, Yadi, et al. “Network-Based Drug Repurposing for Novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2.” Cell Discovery, vol. 6, no. 1, Mar. 2020, pp. 1–18. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-020-0153-3.