Key Takeaways:

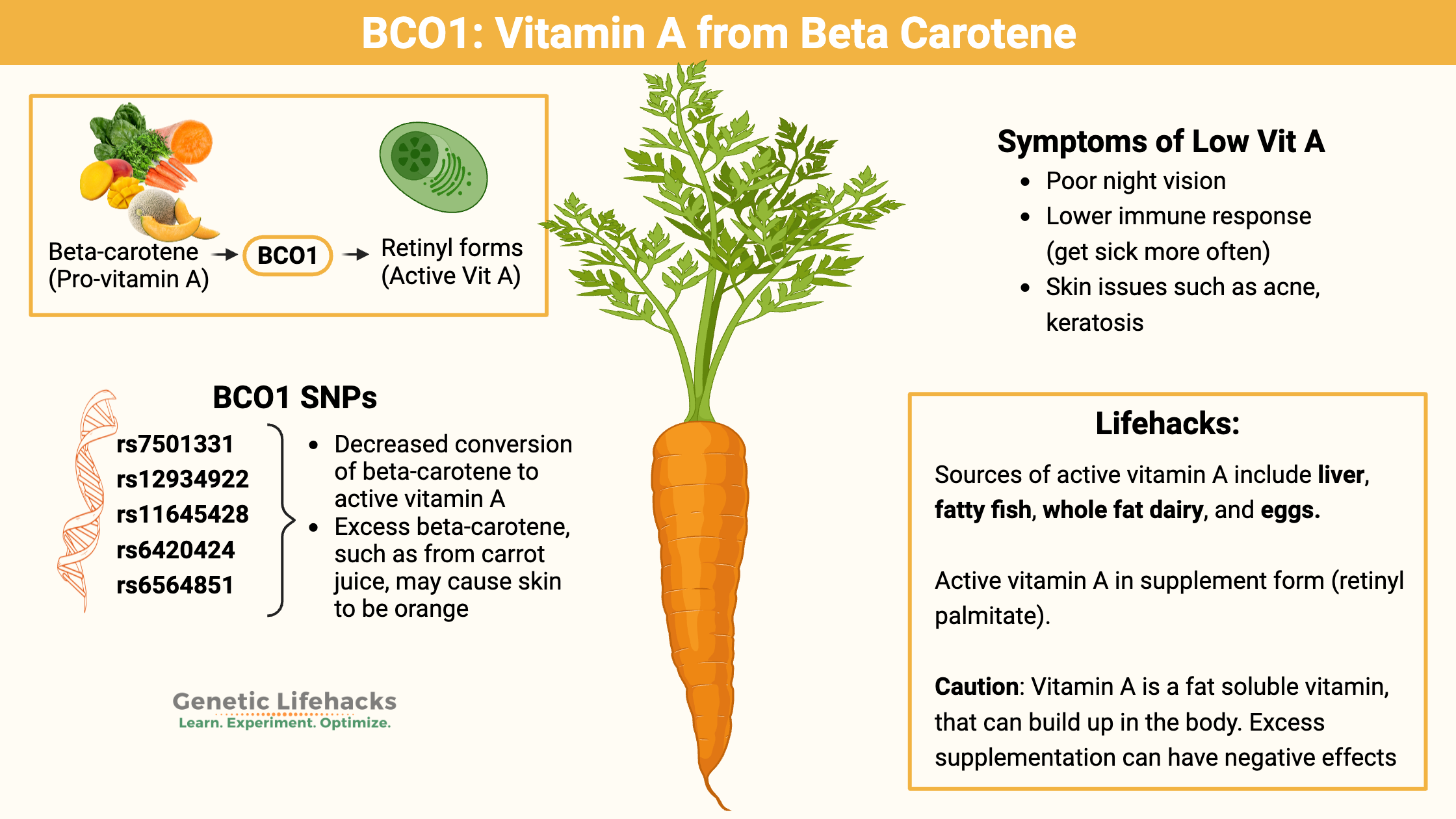

~Beta-carotene is converted to active vitamin A by the BCO1 gene.

~Variants in the BCO1 gene decrease the conversion of beta-carotene to the active form of vitamin A used by the body. This means that people with BCO1 variants may not be getting as much vitamin A from plant sources.

~Low vitamin A can lead to poor night vision, skin problems, and lower immune response.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

Vitamin A and Beta Carotene:

Vitamin A is a general term that covers several different forms of the vitamin.

- Animal food sources mainly provide retinyl palmitate, which breaks down in the intestines into retinol. It is stored, in this form, by the body and then converted to an active form for use.

- Carotenes are the plant forms of a precursor to vitamin A. The most common form, beta-carotene, shows up in abundance in carrots and other orange-colored foods. An enzyme in the intestine breaks down beta-carotene, converting it into retinol.[ref]

Interestingly, most carnivores (entirely meat-eating animals) are poor converters of beta-carotene. For example, cats cannot create any vitamin A from beta-carotene.

How does the body use vitamin A?

About 80-90% of the retinoids in the body are stored in the liver and used to maintain a steady level in the blood.[ref]

The cells in your body use retinoids in a variety of ways.

Retinol is important for:

- Stem cells

- Photoreceptors in the eye

- Epithelial cells

- Embryonic cells

- Various immune cells

- Red blood cells

- Circadian rhythm

Deficiency: A deficiency in vitamin A can cause poor night vision, worsen infectious diseases, and, when severe, cause blindness. In the immune system, retinol is involved with both innate and adaptive immune responses.[ref]

Skin problems: Low levels of vitamin A may cause skin problems such as some types of acne and keratosis pilaris (bumps on the back of the arms).[ref]

How is beta-carotene absorbed?

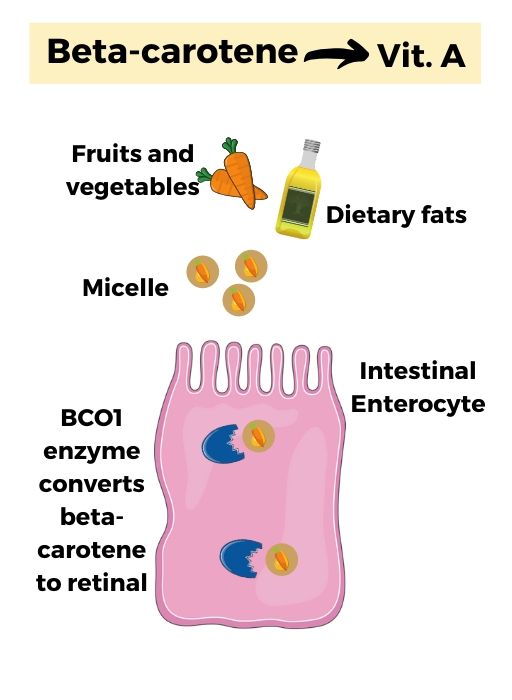

Carotenoids, including beta-carotene, are produced by a number of different plants and some microorganisms (bacteria and algae). While over 600 different carotenoids are produced in nature, only about 20 have been identified in humans via their dietary intake. The primary sources of carotenoids in the diet are colorful fruits and vegetables, such as carrots and spinach.[ref]

Beta-carotene (and all the carotenoids) are fat-soluble micronutrients. They are digested in the upper part of the digestive tract and dissolve in any available fat from the meal. It forms a micelle (droplets of fat surrounding a molecule), easily absorbed in the intestines.

Processing – or how the food is prepared – also impacts the absorption of beta-carotene. A study investigating the bioavailability of beta-carotene and other carotenoids found that raw carrots had about a 2% bioavailability for beta-carotene, while carrot juice was much higher at 14%.[ref]

Within the intestines, the beta-carotene has to be taken into the intestinal cells, called enterocytes. Recent research shows that there are a couple of transporters that facilitate this process.[ref]

How is beta-carotene converted to vitamin A?

Once beta-carotene has been digested, mixed with fats, and absorbed, it has to be converted into retinol. This conversion uses the enzyme β-carotene 15,15′-monooxygenase (BCO1 gene), which converts beta-carotene into retinal. The retinal converts into retinol.[ref] BCO1 is also known as BCMO1.

Genetic variants in the BCO1 gene cause varying amounts of the enzyme to be produced and cause a large difference in the amount of vitamin A produced from dietary beta-carotene.

There is also a feedback loop in the body where higher levels of retinoic acid will decrease the production of the BCO1 enzyme, thus decreasing the amount of beta-carotene converted to retinal.[ref]

The BCO1 enzyme is active in the intestines, liver, and mucosal epithelium (e.g., lining of the lungs). As a result, the conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A occurs in all of those locations.[ref]

Are you turning orange from carrot juice?

Interestingly, up to 40% of carotenoids are not metabolized and used by the body.[ref] This can have consequences when you consume a lot of foods high in beta-carotene.

For example, excessive consumption of carrot juice causes your skin to take on an orange-ish hue called carotenemia.[ref]

A carotenoid reflection spectroscopy device (called the Veggie Meter :-) tests the changes in skin hue from carotenoid consumption.[ref]

The orangish coloration in some salmon species is another example of beta-carotene not being converted. Salmon do not convert carotenoids into vitamin A very well and thus accumulate these colorful nutrients in their flesh, depending on the carotenoid content of their diet.[ref]

Is consuming large amounts of beta-carotene healthy?

Some people consider turning orange from too much beta-carotene benign, but studies indicate excess beta-carotene may not be a good thing.

Eating carrots: Overall mortality rates are lower in people with higher levels of beta-carotene. It indicates links between higher fruit and vegetable consumption and lower all-cause mortality.[ref] A recent meta-analysis found that carrot consumption specifically reduced cancer risk.[ref]

Increased Cancer Mortality: On the other hand, large studies using beta-carotene supplementation to prevent cancer showed increased deaths linked to beta-carotene supplementation for a couple of specific types of cancer.

One large study (18,000+ people) included smokers, former smokers, and people exposed to asbestos. Half of the study participants received a combo of beta-carotene and vitamin A, and the other half received a placebo. The results showed a 46% increase in the relative risk of lung cancer in the group receiving the beta-carotene and vitamin A supplement. Researchers had to end the trial early to prevent more deaths![ref][ref]

Another large study examined the effects of supplementing with beta-carotene, vitamin E, a combo of both, or a placebo. Again, an association exists between beta-carotene supplementation and an increased risk of lung cancer, especially in smokers.[ref]

Several smaller studies back up the large studies with the same results:

- Beta-carotene (20 – 30 mg/day) increases the risk of lung cancer in smokers.[ref]

- Beta-carotene supplementation also increases the risk of bladder cancer a little bit.[ref]

Why would high doses of beta-carotene cause an increase in cancer risk?

Research shows that carotenoids can act as pro-oxidants at higher levels. The breakdown products from beta-carotene include aldehydes and epoxides, which impair mitochondrial function.[ref]

Similarly, animal studies show that low-dose beta-carotene supplementation is health-promoting after a heart attack but that higher doses are not beneficial and possibly deleterious.[ref]

Animal studies also show that high doses of beta-carotene also cause lung cancer in animals exposed to cigarette smoke. The high beta-carotene actually caused an increase in enzymes that destroyed retinoic acid (the active form of vitamin A).[ref] Paradoxically, high levels of beta-carotene act as a pro-oxidant and also decrease retinoic acid.

Why does carrot intake correlate to lower cancer risk? It’s not the beta carotene…

Eating carrots is strongly tied to lower rates of cancer, and eating 5 servings of carrots/week (3-4 medium carrots per week) reduces cancer rates by 20%. The key is that carrots contain compounds other than beta-carotene. [ref]

Falcarinol is also found abundantly in carrots. Studies show that falcarinol and similar compounds reduce cancer cell viability.[ref][ref] The peel of the carrot contains the most falcarinol.

Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk tied to Beta-Carotene Supplementation:

Similar to the cancer studies, large studies of supplemental beta-carotene for reducing cardiovascular disease also show that it is associated with a slight increase in cardiovascular disease mortality and stroke.[ref][ref]

An analysis of cardiovascular mortality risk based on serum β-carotene concentrations also found that people in the top quartile of levels were at more than double the risk of cardiovascular mortality.[ref]

What else does BCO1 (BCMO1) do?

While this article has focused on beta-carotene, the BCMO1 enzyme converts other carotenoids, such as lycopene.

Lycopene is a bright red carotenoid found in tomatoes, watermelon, and papayas.

The variants below that affect beta-carotene conversion may also affect how the body reacts to lycopene. One study on men with prostate cancer showed a trend toward BCMO1 variants impacting the benefits of dietary lycopene consumption.[ref]

Beta-Carotene Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks for Poor Beta-Carotene Conversion

If you have genetic variants that decrease the BCO1 enzyme production, you may wonder if it is worthwhile to eat vegetables. The answer seems to be yes. A study examining the effects of the BCO1 genetic variants on lung cancer risk and fruit and vegetable consumption found that, regardless of enzyme function, higher fruit and vegetable consumption reduced the risk of lung cancer considerably.[ref] There’s more than just beta-carotene in vegetables.

Test your vitamin A levels:

If you have symptoms of vitamin A deficiency (poor night vision, lowered immunity, skin problems, keratosis pilaris, etc.), check your vitamin A levels with a blood test. You could get this through your doctor or order it online. (UltaLab Tests – Vitamin A Retinol – $63)

Foods rich in the active form of vitamin A:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Vitamin D and Your Genes

Your vitamin D levels are impacted by sun exposure – and your genes. Learn more about how vitamin D is made in the body and how your genetic variants impact your levels

Choline – Should you eat more?

An essential nutrient, your need for choline from foods is greatly influenced by your genes. Find out whether you should be adding more choline into your diet.

Folate & MTHFR

The MTHFR gene codes for a key enzyme in the folate cycle. MTHFR variants can decrease the conversion to methyl folate.

Vitamin C: Do you need more?

Like most nutrients, our genes play a role in how vitamin C is absorbed, transported, and used by the body. This can influence your risk for certain diseases, and it can make a difference in the minimum amount of vitamin C you need to consume each day.

References:

Al Nasser, Yasser, et al. “Carotenemia.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2021. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534878/.

Albanes, D., et al. “Alpha-Tocopherol and Beta-Carotene Supplements and Lung Cancer Incidence in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study: Effects of Base-Line Characteristics and Study Compliance.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 88, no. 21, Nov. 1996, pp. 1560–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/88.21.1560.

Borel, Patrick, et al. “Genetic Variants in BCMO1 and CD36 Are Associated with Plasma Lutein Concentrations and Macular Pigment Optical Density in Humans.” Annals of Medicine, vol. 43, no. 1, Feb. 2011, pp. 47–59. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2010.531757.

Castenmiller, J. J., and C. E. West. “Bioavailability and Bioconversion of Carotenoids.” Annual Review of Nutrition, vol. 18, 1998, pp. 19–38. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.18.1.19.

Csepanyi, Evelin, et al. “The Effects of Long-Term, Low- and High-Dose Beta-Carotene Treatment in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats: The Role of HO-1.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 19, no. 4, Apr. 2018, p. E1132. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041132.

Czeczuga-Semeniuk, Ewa, et al. “The Preliminary Association Study of ADIPOQ, RBP4, and BCMO1 Variants with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and with Biochemical Characteristics in a Cohort of Polish Women.” Advances in Medical Sciences, vol. 63, no. 2, Sept. 2018, pp. 242–48. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advms.2018.01.002.

Dorazio, Sarina J., and Christian Brückner. “Why Is There Cyanide in My Table Salt? Structural Chemistry of the Anticaking Effect of Yellow Prussiate of Soda (Na 4 [Fe(CN) 6 ]·10H 2 O).” Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 92, no. 6, June 2015, pp. 1121–24. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1021/ed500776b.

Fortmann, Stephen P., et al. “Vitamin and Mineral Supplements in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 159, no. 12, Dec. 2013, pp. 824–34. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-159-12-201312170-00729.

Helgeland, Hanna, et al. “Genomic and Functional Gene Studies Suggest a Key Role of Beta-Carotene Oxygenase 1 like (Bco1l) Gene in Salmon Flesh Color.” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2019, p. 20061. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56438-3.

Huang, Jiaqi, et al. “Serum Beta-Carotene and Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Cohort Study.” Circulation Research, vol. 123, no. 12, Dec. 2018, pp. 1339–49. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313409.

Lee, Seung-Ah, et al. “Cardiac Dysfunction in β-Carotene-15,15′-Dioxygenase-Deficient Mice Is Associated with Altered Retinoid and Lipid Metabolism.” American Journal of Physiology – Heart and Circulatory Physiology, vol. 307, no. 11, Dec. 2014, pp. H1675–84. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00548.2014.

Leung, W. C., et al. “Two Common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Gene Encoding Beta-Carotene 15,15’-Monoxygenase Alter Beta-Carotene Metabolism in Female Volunteers.” FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, vol. 23, no. 4, Apr. 2009, pp. 1041–53. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.08-121962.

—. “Two Common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Gene Encoding Beta-Carotene 15,15’-Monoxygenase Alter Beta-Carotene Metabolism in Female Volunteers.” FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, vol. 23, no. 4, Apr. 2009, pp. 1041–53. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.08-121962.

—. “Two Common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Gene Encoding Beta-Carotene 15,15’-Monoxygenase Alter Beta-Carotene Metabolism in Female Volunteers.” FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, vol. 23, no. 4, Apr. 2009, pp. 1041–53. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.08-121962.

Lietz, Georg, et al. “Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Upstream from the β-Carotene 15,15’-Monoxygenase Gene Influence Provitamin A Conversion Efficiency in Female Volunteers.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 142, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 161S-5S. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.140756.

Navarro-Valverde, Cristina, et al. “High Serum Retinol as a Relevant Contributor to Low Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Osteoporotic Women.” Calcified Tissue International, vol. 102, no. 6, June 2018, pp. 651–56. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0379-8.

Novotny, Janet A., et al. “Beta-Carotene Conversion to Vitamin A Decreases as the Dietary Dose Increases in Humans.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 140, no. 5, May 2010, pp. 915–18. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.116947.

Omenn, G. S., et al. “Effects of a Combination of Beta Carotene and Vitamin A on Lung Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 334, no. 18, May 1996, pp. 1150–55. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199605023341802.

Park, So Jung, et al. “Effects of Vitamin and Antioxidant Supplements in Prevention of Bladder Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Journal of Korean Medical Science, vol. 32, no. 4, Apr. 2017, pp. 628–35. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.4.628.

Reboul, Emmanuelle, et al. “Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids and Vitamin E from Their Main Dietary Sources.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, vol. 54, no. 23, Nov. 2006, pp. 8749–55. ACS Publications, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf061818s.

—. “Mechanisms of Carotenoid Intestinal Absorption: Where Do We Stand?” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2019, p. 838. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040838.

—. “Mechanisms of Carotenoid Intestinal Absorption: Where Do We Stand?” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2019, p. 838. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040838.

—. “Mechanisms of Carotenoid Intestinal Absorption: Where Do We Stand?” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2019, p. 838. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040838.

Ribaya-Mercado, Judy D., et al. “Carotene-Rich Plant Foods Ingested with Minimal Dietary Fat Enhance the Total-Body Vitamin A Pool Size in Filipino Schoolchildren as Assessed by Stable-Isotope-Dilution Methodology.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 85, no. 4, Apr. 2007, pp. 1041–49. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/85.4.1041.

Rush, Elaine, et al. “Determinants and Suitability of Carotenoid Reflection Score as a Measure of Carotenoid Status.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2020, p. E113. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010113.

Russell, Robert M. “The Enigma of Beta-Carotene in Carcinogenesis: What Can Be Learned from Animal Studies.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 134, no. 1, Jan. 2004, pp. 262S-268S. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/134.1.262S.

S, Ragunatha, et al. “Therapeutic Response of Vitamin A, Vitamin B Complex, Essential Fatty Acids (EFA) and Vitamin E in the Treatment of Phrynoderma: A Randomized Controlled Study.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 116–18. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/7086.3918.

Seino, Yusuke, et al. “Isx Participates in the Maintenance of Vitamin A Metabolism by Regulation of Beta-Carotene 15,15’-Monooxygenase (Bcmo1) Expression.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 283, no. 8, Feb. 2008, pp. 4905–11. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M707928200.

Siems, Werner, et al. “Beta-Carotene Breakdown Products May Impair Mitochondrial Functions–Potential Side Effects of High-Dose Beta-Carotene Supplementation.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 16, no. 7, July 2005, pp. 385–97. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.009.

Stephensen, C. B. “Vitamin A, Infection, and Immune Function.” Annual Review of Nutrition, vol. 21, 2001, pp. 167–92. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.167.

Tanvetyanon, Tawee, and Gerold Bepler. “Beta-Carotene in Multivitamins and the Possible Risk of Lung Cancer among Smokers versus Former Smokers: A Meta-Analysis and Evaluation of National Brands.” Cancer, vol. 113, no. 1, July 2008, pp. 150–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23527.

“Top 10 Foods Highest in Beta Carotene.” Myfooddata, https://www.myfooddata.com/articles/natural-food-sources-of-beta-carotene.php. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021.

Toti, Elisabetta, et al. “Non-Provitamin A and Provitamin A Carotenoids as Immunomodulators: Recommended Dietary Allowance, Therapeutic Index, or Personalized Nutrition?” Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2018, May 2018, p. 4637861. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4637861.

“Vitamin A.” Linus Pauling Institute, 22 Apr. 2014, https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/vitamins/vitamin-A.