Key takeaways:

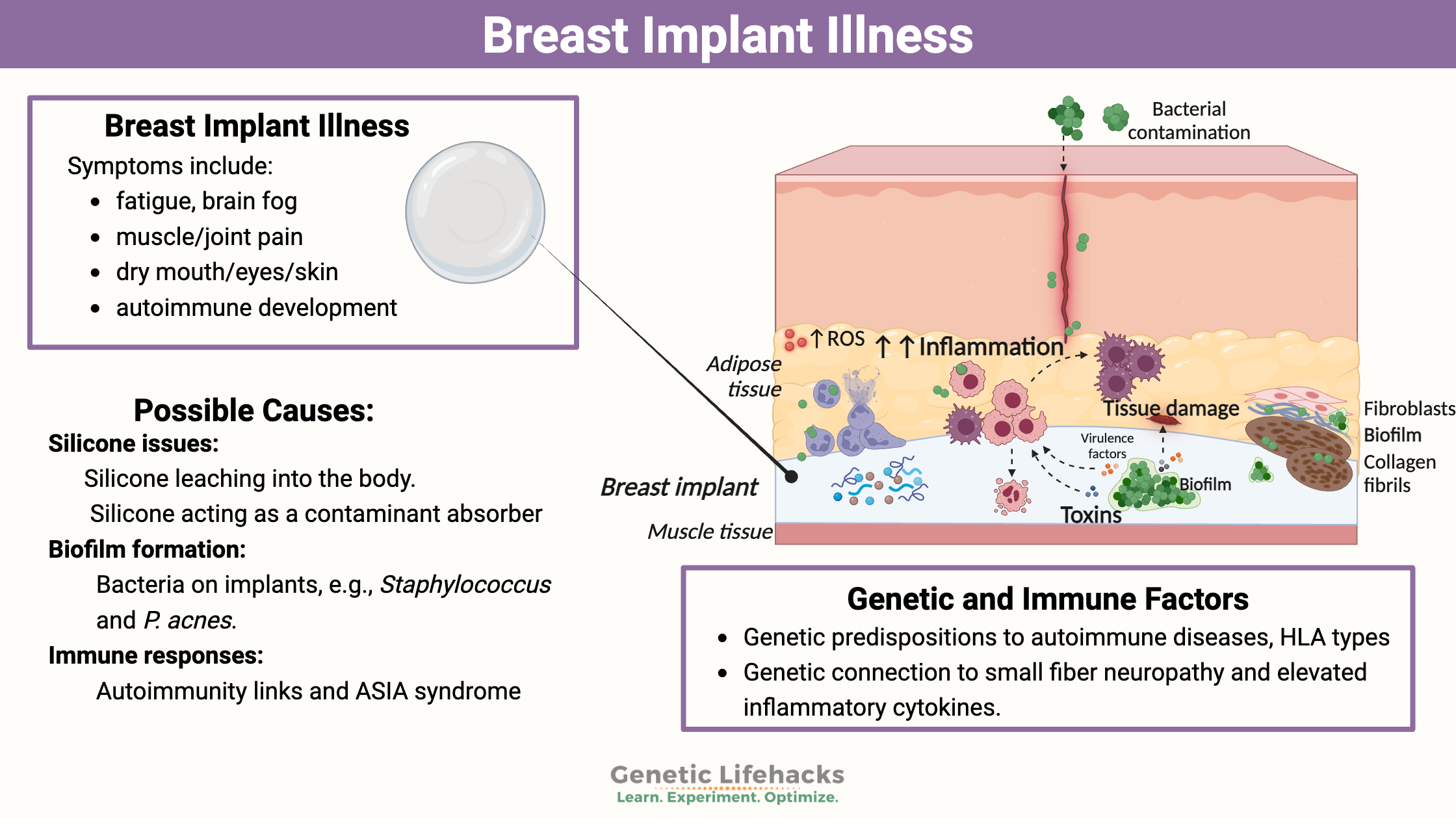

~ Breast implant illness causes symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and brain fog.

~ Researchers think BII is caused by an immune system reaction triggered by the silicone or to microbial growth.

~ Genetic variants are linked to susceptibility to various symptoms of BII such as small fiber neuropathy or immune system changes.

This article explores the research on breast implant illness — from whether or not it is real to research on underlying causes. Included is information on genetic variants that research links to increased susceptibility to BII and possible solutions. Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

What is Breast Implant Illness?

Breast implants have been around since the 1960s, and for decades, women have reported symptoms that start sometime after getting breast implants.

In the 1990s, the FDA mandated a moratorium on breast implants to investigate their safety more thoroughly. The halt on implants was based on case reports of women diagnosed with T-cell lymphoma and other illnesses after their silicone implants. A flurry of studies in the early 2000s showed that there wasn’t a statistical increase in cancer risk, and the FDA reapproved the use of breast implants in 2006.[ref]

While a link to increased T-cell lymphoma wasn’t found by the FDA studies, women still continue to report a cluster of symptoms after breast implants.

Symptoms reported with breast implant illness include:[ref][ref]

- fatigue, constant tiredness

- muscle pain, morning stiffness

- joint pain

- dry mouth, dry eyes, dry skin

- brain fog

- fever

- peripheral neurological symptoms

- development of autoimmune diseases

For some, these symptoms may begin soon after implantation, but for others, the symptoms can appear years later.

As you can see, these symptoms overlap with other chronic conditions, including several autoimmune diseases. Identifying the root cause of your fatigue, aches, and cognitive issues can be challenging.

Doctors may try to first rule out other diseases with similar symptoms, such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, fibromyalgia, or chronic Lyme disease.

Explantation (removal) proves that BII is a real illness

Breast implant illness isn’t recognized by all doctors as a diagnosis. The symptoms are vague and not always directly tied to the area of the implant, leading to many in the medical community questioning the validity of the disease. Silicone has long been considered an inert substance to put into the body.

If breast implants are causing illness, it makes sense that removing the implant would make the symptoms better…

Recent research shows this is true. Taking out breast implants (explantation) improves symptoms for many women with breast implant illness.

- In one study, 94% of women with BII symptoms had improvement. Notably, the symptom improvement seems to last. At six months, the women had a 68% reduction in the number of symptoms. Fatigue, brain fog, joint pain, and muscle pain showed the most improvement.[ref]

- Another study found that 67% of women with BII had symptom improvement after explantation.[ref]

Explantation may not be an option for everyone, though. It is a medical surgery procedure that is not without risk and financial cost. Additionally, the remaining breast tissue may need additional cosmetic procedures. Thus, explantation may not be a realistic option for everyone.

Possible Causes of Breast Implant Illness

While symptoms from breast implants have been reported for decades, research on breast implant illness has increased over the past few years.

Forums and social media groups have raised awareness of the connection of the symptoms to the implants. Momentum has grown to find an underlying cause, and quite a bit of research has been done recently.

The following themes are found in research on BII:

- it is psychosomatic

- silicone leaching or rupture

- bacterial biofilm

- autoimmune disease

- a subset of ASIA syndrome

1) Psychosomatic (Is it all in your head?):

The idea that breast implant illness is psychosomatic has been proposed and studied by several researchers. For example, some researchers call breast implant illness a “model of psychological illness”. It was based on a mailed survey that showed women with breast implants having higher anxiety scores than female undergraduate students.[ref]

In another research article in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (BMJ), the author likened the symptoms that women have attributed to breast implants to “similar symptoms in fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and other contexts have been considered to be stress or behaviourally mediated, and a number of promising behavioral interventions have been developed.” It goes on to say that “In the case of implants, a mass somatisation model may also help to discern the potential effects of litigation and other social influences.” In other words, it’s all in your head.[ref]

A 2022 review article explained that breast implant illness is most likely psychosomatic and a social media phenomenon.[ref] Considering that the research on the symptoms from breast implants dates back decades before social media or the internet, I question their logic on this one.

Just as a quick aside: I’ve often read the argument that people with anxiety are more likely to report weird symptoms — from long Covid, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue to BII. It immediately makes some people think that an illness or symptom is likely ‘all in the head’. (To be honest, I have likely thought that way in the past.) However, research now clearly shows that elevated inflammatory cytokines can cause anxiety and/or depression. Thus, in people with chronic illness who have elevated inflammation, you should expect a higher number to also notice anxiety or other brain-related symptoms. In other words, instead of anxiety causing them to make up symptoms, the physiological effects of inflammation in the body are causing cognitive changes.

Moving on to the bulk of the scientific research on BII…

2) Silicone Leaching or Rupture:

Quite a bit of research shows that silicone can bleed out into the body from implants. For example, silicone particles are found in the lymph nodes, spleen, and liver after a rupture. However, silicone is supposed to be a biologically inert material and theoretically shouldn’t cause a problem in the body.[ref]

In women without implant ruptures, almost all (99%) had silicone particles present in various tissues. According to the study’s authors, this indicates that silicone gel inserts give off a little bit of silicone that can then migrate throughout the body. The study included both older type implants as well as newer cohesive gel implants. Silicone was found in the lymph nodes and the tissue around the implant.[ref]

While biologically inert, silicones can trigger an immune response. Higher levels of silicone in tissues correlate to increased macrophages in the tissue. Macrophages are a type of white blood cell that migrate to sites of inflammation to engulf foreign substances.[ref]

Terminology time out: Silicone is a polymer made of silicon (an element) combined with other substances to make it flexible and rubber-like. There are lots of different types of silicones. Silica, on the other hand, is silicon dioxide, which occurs in quartz and sand. Silica can be used to manufacture silicone. Silicosis is the term applied to a disease usually caused by inhaling silica as small dust particles.

In addition to breast implants, silicone is used in medical devices and coating prefilled syringes. The coating then causes silicone particles to be injected when prefilled syringes are used. Additionally, silicone is used in dermal fillers. Granulomas, which are small areas of pus or inflammation, are a well-documented response to injected silicone and can occur up to 10 to 15 years after injection.[ref][ref]

If silicone is totally inert, why would the body react to it? One theory is that silicone causes a mechanical cell response due to the stiff interface encountered by bodily fluids. Even viscous gel silicones have a surface rigidity different from normal cells and can activate macrophages.[ref]

Other research indicates that the ‘gel bleed’ from silicone breast implants may not be as “inert” as originally thought. Microdroplets of the methylsiloxanes, one of the smallest silicone particles found in breast implants, cause cell death in lab testing.[ref]

The size and amount of particulate debris released from breast implants depend on the type of implant surface and the manufacturer. Of note, all implants give off particulate materials.[ref]

Additionally, research on silicone dermal fillers showed that they cause IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, to be elevated. The study did show that CD4+ T cells were not activated, indicating inflammatory cytokines but not antibodies.[ref]

Silicone absorbs contaminants…

In a study looking at persistent chemical toxicants (things like pesticides and other pollutants), researchers found that breast implants act as passive samplers, absorbing contaminants from the body.

It turns out silicone breast implants are much like the silicone rubbers used in environmental sampling devices to trap pollutants.

The researchers found fourteen compounds in the eight extracted breast implants – fragrances, dyes, pesticides, and flame retardants. They even found a metabolite of DDT, which is a pesticide that has been banned in the US since 1972 but still persists in the environment.[ref]

3) Bacterial Biofilm

One problem with any implant – whether breast, tooth, knee, screws, mesh, or other implants – is a possibility of a bacterial biofilm forming on the implanted material.[ref][ref][ref]

When bacteria are in an environment that is not ideal, they can mass together and form a niche environment where they can colonize and proliferate. They form a ‘film’ by producing proteins and exopolysaccharides.[ref]

In the lab, researchers evaluated how biofilm forms on silicone. They found that multiple bacterial species can form biofilms on silicone, and this is exacerbated by collagen being available.[ref] While silicone isn’t a medium for bacterial growth, when the implants are inside the body, a matrix of proteins forms around them that can facilitate biofilm formation.[ref]

Breast implants that have been removed show positive results for bacteria. Staphylococcus was the most commonly associated bacteria.[ref][ref]

In a study involving 50 patients with BII, removed implants showed that 36% had a chronic infection. Propionibacterium acnes was the most prominent organism found.[ref]

Quick aside: Propionibacterium acnes is the bacteria that commonly cause acne on the skin. But it is also found in the spine of people having back surgery for disk degeneration pain. (Read more about it here.)

While it can be weird to think about, we humans are hosts to many microbes — from the gut microbiome to the mouth to the skin. As research gets better at detecting and isolating bacteria, even areas of the body that were thought to be sterile, such as the uterus, bladder, and breast tissue, all have bacteria present.

The question in my mind is whether the bacterial biofilm on breast implants causes symptoms of BII or is incidental. Researchers have investigated biofilm formation more extensively for other implants, such as knees and hips. Bacteria that form biofilms and survive also release extracellular DNA. It can be measured, and researchers have found increased eDNA in people with implants. Most commonly, the eDNA is from Staphylococcus species.[ref]

4) Fungal infection:

Another possible culprit in BII is a fungal infection. A recent case study reported a Penicillium fungal species along with Propionibacterium acnes on the implant. The removed implants had “a visible white coating on the outside with turbid green fluid with small debris inside”. Of note here is that the patient also had pain in the breast area. A few other case studies also show fungal infections, but it seems to be uncommon.[ref][ref] A lab-based study showed that Aspergillus niger could multiply in saline-filled silicone implants, but Candida doesn’t live all that long.[ref] Another case study reported on Aspergillus species found both inside and outside an implant that had been inserted 18 months prior. This case study reported that the silicone implant is selectively permeable.[ref]

Again, from the case reports, it seems like fungal infections are uncommon, but I include them here in case the symptoms fit someone.

5) BII is an autoimmune disease

The symptoms of breast implant illness are systemic and varied, much like an autoimmune disease. Plus, the symptoms overlap a lot with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and lupus — all of which have systemic and varied symptoms.

A large study published in 2018 found that patients with silicone breast implants were at an increased relative risk of autoimmune diseases. Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, Raynaud’s, and sarcoidosis were the most common.[ref]

A study in Danish women with rheumatic disorders and breast implants found that the presence of antipolymer antibodies didn’t correlate with rheumatic symptoms.[ref]

A recent study published in Jun 2022 found that women with BII who reported cognitive issues were more likely to have autoantibodies against autonomic nervous system receptors (adrenergic, muscarinic, endothelin receptors). Another study by the same researchers looked at BII patients with palpitations, pain, depression, hearing loss, dry eyes, and dry mouth. The results showed they were more likely to have dysregulation of autoantibodies against a different type of autonomic nervous system receptors.[ref]

The question then is whether the breast implants trigger autoimmune diseases or if underlying autoimmune diseases are causing the symptoms that people associate with BII. Both could be true, and it is likely a question that may take a lot of testing to answer for an individual.

ASIA Syndrome: Overarching Category?

ASIA syndrome (autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants) is a term that comes up in research about breast implants. Essentially, ASIA is a more encompassing term that would also include other types of implanted materials as well, such as adjuvants in vaccines or chronic industrial exposure to silicone. Also included in ASIA syndrome are injected fillers, some of which may also contain silicone.[ref]

A case study explains a woman diagnosed with ASIA syndrome three years after implant. The patient chose not to have explantation and could control the symptoms with daily hydroxychloroquine to suppress her immune response.[ref]

A 2017 retrospective study examined whether breast implant patients diagnosed with ASIA syndrome had the same symptoms as those diagnosed with Silicone Implant Incompatibility Syndrome. The results showed that the symptoms reported by women after breast implants have remained the same for 30+ years, no matter which disease label is used.[ref]

Small fiber neuropathy in BII

Breast implant illness, also called silicone implant incompatibility syndrome, is also linked in several studies to small fiber neuropathy. The connection is thought to be autoantibodies against the G-protein coupled receptors in small nerves.[ref] One study of 500 patients with silicone breast implant symptoms found that 87% appeared to have a neuropathy.[ref]

Small fiber neuropathy is caused by damage to the tiny nerve fibers that carry information about pain, temperature, and touch. In addition to causing tingling and odd sensations in the periphery, small fiber neuropathy can also affect autonomic nervous system functions like heart rhythm, bladder function, and the gastrointestinal tract.

In addition to links to breast implant illness, small fiber neuropathy also occurs in RA, sarcoidosis, and other autoimmune diseases.

Breast Implant Illness Genotype Report

While several recent studies are looking at possible reasons for BII (biofilms, autoimmunity, silicone reactions), research studies have not been done to link genetic variants directly to breast implant illness. Articles by clinicians indicate that some doctors think that MTHFR, MTRR, and HLA genes are likely linked to an increased risk of breast implant illness. These suppositions are based on their observations of a limited number of patients rather than statistical research studies.

Autoimmune genes: The HLA family of serotypes is linked to many different autoimmune diseases. In 1995, a research study found that the HLA-DR53 family, which consists of several HLA types, increased susceptibility to breast implant illness. This family of HLA types cannot be determined from your genetic raw data file.

Does this mean that genetics has no impact on breast implant illness? Not at all. It simply means that the research hasn’t been done. Studies on silicone implant-induced immune responses have been done in rats. The researchers found that four autoimmune-related genes were likely involved in the response. These genes include Tlr6, Tlr2, Gata3, and Aif1. Hopefully, the researchers will take the next step in human genetics studies, but the animal studies paint the picture of a localized immune reaction after silicone implantation.

Instead of direct research, I’m going to include some genes strongly linked to related autoimmune diseases — and also address some of the speculative information I’ve seen in articles.

Autoimmune Links:

The following genes have been linked in peer-reviewed research studies to autoimmune diseases that overlap with breast implant illness.

Lifehacks for Breast Implant Illness:

Right now, there are a lot more questions than answers surrounding BII.

Talk with your doctor or plastic surgeon about your options and testing for specific autoimmune diseases.

Supporting a healthy immune response:

Diet and lifestyle factors play a role in many autoimmune diseases. Generally, a whole foods diet that avoids common immune system triggers is often recommended for autoimmune diseases. Simply switching to whole foods cooked from scratch helps avoid many of the possible triggers found in highly processed foods. Look into Autoimmune Protocol if you need diet help.

If your breast implant symptoms started after the COVID-19 vaccination, you are not alone. A journal letter explained that similar to dermal facial filler reactions, the practitioners saw many potential reactions associated with breast implants one to three days post-vaccination. The authors note that the reactions are a rare side effect and are not seen in all women with breast implants.[ref] Another journal article details a number of published case studies on breast implant side effects from vaccination.[ref]

Research on 5 Supplements for breast implant illness:

Related Articles and Topics:

Detoxification Genes Overview

Learn how phase I and phase II detoxification works and how your genes impact these enzymes.

Small fiber neuropathy:

Damage to the small nerve fibers can cause a variety of symptoms, from peripheral tingling to autonomic nervous system dysfunction.

Nickel Allergy: Genetics, causes, natural solutions

Nickel allergy can cause sensitivity to foods that contain nickel. Learn about how genes increase susceptibility and solutions.

Gut Genes

This article digs into how the genetic variants you inherited from mom and dad influence the bacteria that can reside within you and how dietary changes can make a difference.

References:

Ahern, M., et al. “Breast Implants and Illness: A Model of Psychological Illness.” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 61, no. 7, July 2002, p. 659. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.61.7.659.

Atiyeh, Bishara, and Saif Emsieh. “Breast Implant Illness (BII): Real Syndrome or a Social Media Phenomenon? A Narrative Review of the Literature.” Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, vol. 46, no. 1, Feb. 2022, pp. 43–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-021-02428-8.

Busscher, H. J., et al. “Biofilm Formation on Dental Restorative and Implant Materials.” Journal of Dental Research, vol. 89, no. 7, July 2010, pp. 657–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510368644.

Chávez-Castillo, Mervin, et al. “Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: The Future of Chronic Pain Therapy?” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 19, Sept. 2021, p. 10370. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910370.

Cheng, Zhu, et al. “The Surface Stress of Biomedical Silicones Is a Stimulant of Cellular Response.” Science Advances, vol. 6, no. 15, Apr. 2020, p. eaay0076. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay0076.

Cohen Tervaert, J. W., et al. “Breast Implant Illness: Scientific Evidence of Its Existence.” Expert Review of Clinical Immunology, vol. 18, no. 1, Jan. 2022, pp. 15–29. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2022.2010546.

Colaris, Maartje J. L., Mintsje de Boer, et al. “Two Hundreds Cases of ASIA Syndrome Following Silicone Implants: A Comparative Study of 30 Years and a Review of Current Literature.” Immunologic Research, vol. 65, no. 1, 2017, pp. 120–28. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-016-8821-y.

Colaris, Maartje J. L., Rene R. van der Hulst, et al. “Vitamin D Deficiency as a Risk Factor for the Development of Autoantibodies in Patients with ASIA and Silicone Breast Implants: A Cohort Study and Review of the Literature.” Clinical Rheumatology, vol. 36, no. 5, May 2017, pp. 981–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3589-6.

de la Visitación, Néstor, et al. “Probiotics Prevent Hypertension in a Murine Model of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Induced by Toll-Like Receptor 7 Activation.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 8, July 2021, p. 2669. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082669.

Dijkman, Henry B. P. M., et al. “Assessment of Silicone Particle Migration Among Women Undergoing Removal or Revision of Silicone Breast Implants in the Netherlands.” JAMA Network Open, vol. 4, no. 9, Sept. 2021, p. e2125381. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25381.

Dush, D. “Breast Implants and Illness: A Model of Psychological Factors.” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 60, no. 7, July 2001, pp. 653–57. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.60.7.653.

Fan, Xin, et al. “A Rare Fungal Species, Quambalaria Cyanescens, Isolated from a Patient after Augmentation Mammoplasty–Environmental Contaminant or Pathogen?” PloS One, vol. 9, no. 10, 2014, p. e106949. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106949.

Gellert, Max, et al. “Biofilm-Active Antibiotic Treatment Improves the Outcome of Knee Periprosthetic Joint Infection: Results from a 6-Year Prospective Cohort Study.” International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, vol. 55, no. 4, Apr. 2020, p. 105904. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105904.

Glicksman, Caroline, et al. “Impact of Capsulectomy Type on Post-Explantation Systemic Symptom Improvement: Findings From the ASERF Systemic Symptoms in Women-Biospecimen Analysis Study: Part 1.” Aesthetic Surgery Journal, vol. 42, no. 7, Dec. 2021, pp. 809–19. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab417.

Hallab, Nadim James, et al. “Particulate Debris Released From Breast Implant Surfaces Is Highly Dependent on Implant Type.” Aesthetic Surgery Journal, vol. 41, no. 7, June 2021, pp. NP782–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab051.

Jacombs, A. S. W., et al. “Biofilms and Effective Porosity of Hernia Mesh: Are They Silent Assassins?” Hernia: The Journal of Hernias and Abdominal Wall Surgery, vol. 24, no. 1, Feb. 2020, pp. 197–204. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-02063-y.

Jensen, Bente, et al. “Antipolymer Antibodies in Danish Women with Silicone Breast Implants.” Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants, vol. 14, no. 2, 2004, pp. 73–80. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v14.i2.10.

Kaplan, Jordan, and Rod Rohrich. “Breast Implant Illness: A Topic in Review.” Gland Surgery, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2021, pp. 430–43. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-231.

Kuhn, Natalie, and Christopher Homsy. “Rare Presentation of Breast Implant Infection and Breast Implant Illness Caused by Penicillium Species.” Eplasty, vol. 22, June 2022, p. ic9. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9275409/.

Lee, Jeong Min, and Yu Jin Kim. “Foreign Body Granulomas after the Use of Dermal Fillers: Pathophysiology, Clinical Appearance, Histologic Features, and Treatment.” Archives of Plastic Surgery, vol. 42, no. 2, Mar. 2015, pp. 232–39. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2015.42.2.232.

Lee, Mark, et al. “Breast Implant Illness: A Biofilm Hypothesis.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, vol. 8, no. 4, Apr. 2020, p. e2755. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002755.

Leuti, Alessandro, et al. “Role of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Neuropathic Pain.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 12, Aug. 2021, p. 717993. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.717993.

Ma, Longhuan, and Laurence Morel. “Loss of Gut Barrier Integrity In Lupus.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 13, June 2022, p. 919792. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.919792.

Mangalam, Ashutosh K., et al. “The Emerging World of Microbiome in Autoimmune Disorders:

Opportunities and Challenges.” Indian Journal of Rheumatology, vol. 16, no. 1, Mar. 2021, pp. 57–72. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.4103/injr.injr_210_20.

MD, ARTHUR DALE ERICSSON. “Syndromes Associated with Silicone Breast Implants: A Clinical Study and Review.” Journal of Nutritional & Environmental Medicine, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 1998, pp. 35–51. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/13590849862285.

Miro-Mur, Francesc, et al. “Medical-Grade Silicone Induces Release of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells without Activating T Cells.” Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part B, Applied Biomaterials, vol. 90, no. 2, Aug. 2009, pp. 510–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.31312.

Montealegre, Giovanni, et al. “ASIA Syndrome Symptoms Induced by Gluteal Biopolymer Injections: Case-Series and Narrative Review.” Toxicology Reports, vol. 8, Jan. 2021, pp. 303–14. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.01.011.

Nunes E Silva, Daniel, et al. “Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) after Silicone Breast Augmentation Surgery.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open, vol. 5, no. 9, Sept. 2017, p. e1487. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000001487.

O’Connell, Steven G., et al. “In Vivo Contaminant Partitioning to Silicone Implants: Implications for Use in Biomonitoring and Body Burden.” Environment International, vol. 85, Dec. 2015, pp. 182–88. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.016.

Oliveira, W. F., et al. “Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcus Epidermidis Infections on Implants.” The Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 98, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 111–17. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2017.11.008.

Onnekink, Carla, et al. “Low Molecular Weight Silicones Induce Cell Death in Cultured Cells.” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, June 2020, p. 9558. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66666-7.

Petersen, Anders Ø., et al. “Cytokine-Specific Autoantibodies Shape the Gut Microbiome in Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 1.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 148, no. 3, Sept. 2021, pp. 876–88. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.03.025.

Rezende-Pereira, Gabriel, et al. “Biofilm Formation on Breast Implant Surfaces by Major Gram-Positive Bacterial Pathogens.” Aesthetic Surgery Journal, vol. 41, no. 10, Sept. 2021, pp. 1144–51. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa416.

Saray, Aydin, et al. “Fungal Growth inside Saline-Filled Implants and the Role of Injection Ports in Fungal Translocation: In Vitro Study.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, vol. 114, no. 5, Oct. 2004, pp. 1170–78. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000135855.29657.91.

Shoenfeld, Yehuda, et al. “Complex Syndromes of Chronic Pain, Fatigue and Cognitive Impairment Linked to Autoimmune Dysautonomia and Small Fiber Neuropathy.” Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.), vol. 214, May 2020, p. 108384. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108384.

Spit, Karlinde Amber, et al. “Patient-Reported Systemic Symptoms in Women with Silicone Breast Implants: A Descriptive Cohort Study.” BMJ Open, vol. 12, no. 6, June 2022, p. e057159. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057159.

Suh, Lily J., et al. “Breast Implant-Associated Immunological Disorders.” Journal of Immunology Research, vol. 2022, May 2022, p. 8536149. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8536149.

Tocut, Milena, et al. “Cognitive Impairment, Sleep Disturbance, and Depression in Women with Silicone Breast Implants: Association with Autoantibodies against Autonomic Nervous System Receptors.” Biomolecules, vol. 12, no. 6, June 2022, p. 776. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12060776.

Vaghef-Mehrabany, Elnaz, et al. “Probiotic Supplementation Improves Inflammatory Status in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis.” Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), vol. 30, no. 4, Apr. 2014, pp. 430–35. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2013.09.007.

Walker, Jennifer N., et al. “Deposition of Host Matrix Proteins on Breast Implant Surfaces Facilitates Staphylococcus Epidermidis Biofilm Formation: In Vitro Analysis.” Aesthetic Surgery Journal, vol. 40, no. 3, Feb. 2020, pp. 281–95. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjz099.

Wang, Hannah, et al. “Breast Tissue, Oral and Urinary Microbiomes in Breast Cancer.” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 50, Aug. 2017, pp. 88122–38. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.21490.

Watad, Abdulla, et al. “Silicone Breast Implants and the Risk of Autoimmune/Rheumatic Disorders: A Real-World Analysis.” International Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 47, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 1846–54. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy217.

Weitgasser, Laurenz, et al. “Potential Immune Response to Breast Implants after Immunization with COVID-19 Vaccines.” The Breast : Official Journal of the European Society of Mastology, vol. 59, June 2021, pp. 76–78. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2021.06.002.

Wright, P. K., et al. “The Semi-Permeability of Silicone: A Saline-Filled Breast Implant with Intraluminal and Pericapsular Aspergillus Flavus.” Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery: JPRAS, vol. 59, no. 10, 2006, pp. 1118–21. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2006.01.020.

Zatorska, Beata, et al. “Does Extracellular DNA Production Vary in Staphylococcal Biofilms Isolated From Infected Implants versus Controls?” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, vol. 475, no. 8, Aug. 2017, pp. 2105–13. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5266-0.

Zhang, Jilei, et al. “Breast and Gut Microbiome in Health and Cancer.” Genes & Diseases, vol. 8, no. 5, Sept. 2021, pp. 581–89. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2020.08.002.