Our immune system’s response varies over the course of 24-hours. At certain times, we may be more resilient to fighting off viruses; at other times of the day, we may be more susceptible to pathogens.

For anyone who has traveled across multiple time zones, this altered immune response won’t come as much of a surprise. How many times have you adjusted to jet lag, just to end up with a cold or not feeling well? Similarly, you are at an increased risk of getting sick when staying up late – pulling that all-nighter before finals or working the night shift once in a while.

This article covers the background information on how your circadian rhythm and timing are important in your body’s immune response in general — and the response to viruses such as COVID-19 and the flu. Do you just want to know about COVID-19? Jump ahead to that section.

Related article: Research roundup: Preventing and Mitigating Covid-19

Circadian Rhythms & Immune Function

Background on Circadian Rhythm:

The term circadian comes from Latin, circa diem, meaning about a day. Humans – and actually all animals and plants – have a built-in clock system that controls bodily functions across the course of 24-hours.

The first thing that comes to mind for circadian rhythms is usually the sleep/wake cycle. Humans (and diurnal animals) are naturally awake during the day and sleep about 8 hours at night.

Over the last two decades, researchers have uncovered the genes controlling this built-in clock and discovered that many of the body’s functions happen rhythmically. For example, we don’t produce the enzymes needed to break down different foods during the night when we usually sleep. It turns out that 10 to 40% of our cellular functions are under circadian clock control.[ref]

Resetting the clock:

Our circadian rhythm isn’t exactly 24-hours, and the body uses outside signals to reset the clock each day. Sunlight is the synchronizer of the core circadian clock. The sun comes up every morning… every single day throughout the history of the earth.

In humans, the core circadian pacemaker is located in the hypothalamus, right in the mid-part of the brain. It is called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

The signal that sets that core circadian clock is a specific wavelength of light hitting the eyes. In the retina, you have rods and cones for color and night vision. Additionally, the retina contains non-image-forming photoreceptors with melanopsin. These receptors directly signal the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) to reset the circadian clock.

The melanopsin receptors are triggered or excited, by light in the blue wavelengths. Before electric lights, the only exposure that we had to light in the blue wavelengths was due to sunlight (firelight, candlelight has very little light in the blue wavelengths).

It causes a mismatch in modern times with bright electric lights and blue wavelengths at night battling our evolutionarily conserved mechanism of resetting the circadian clock. Many research studies show the impact of blue light exposure at night on both melatonin and our circadian rhythm.(article)

Peripheral Clocks:

Different tissues and organs throughout the body have their own clock mechanism. These ‘peripheral clocks’ control the rhythm of expression of genes – the creation of different cellular enzymes and proteins – in tissues such as the skin, liver, pancreas, heart, and adrenal glands.

The liver is geared up and ready to produce enzymes needed to break down food (or medicine) at the time of day that you normally eat. Your skin produces different enzymes during the day for battling UV exposure and for making vitamin D. And your vitamin D levels rise and fall in a circadian pattern as well, with a peak mid-day. One study indicates that 25-OH D levels (the commonly tested vitamin D component) can change up to 20% over a 24-hour period. (Something to keep in mind the next time you get blood work done.)[ref][ref]

The key with these peripheral clocks is that they are also affected by your core circadian pacemaker (the SCN) in the hypothalamus. The core circadian clock interacts with the peripheral circadian clocks – and this whole system needs to be in sync for optimal wellness.

For example, the adrenal glands release glucocorticoids, e.g., cortisol, in a rhythm that is (ideally) in sync with the body’s core circadian rhythm. The hypothalamus, where the suprachiasmatic nucleus is located, also directly controls the rhythm of the glucocorticoids. The HPA axis – hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenals axis – receives input directly from the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which receives input from the sun’s natural light/dark cycle.[ref][ref]

Why am I using the HPA axis as an example here? Because the HPA axis is also very important in the body’s immune response…

Circadian rhythm of the immune system:

Key fighters in your body’s defense against pathogens include macrophages and lymphocytes. Macrophages are large white blood cells that patrol and engulf foreign pathogens, cellular debris, and cancer cells. They are found throughout the body. Lymphocytes, which are found in the lymph, are another type of white blood cell that includes T-cells and B-cells.

B-cells are made in the bone marrow, and macrophages are also formed from bone marrow stem cells.

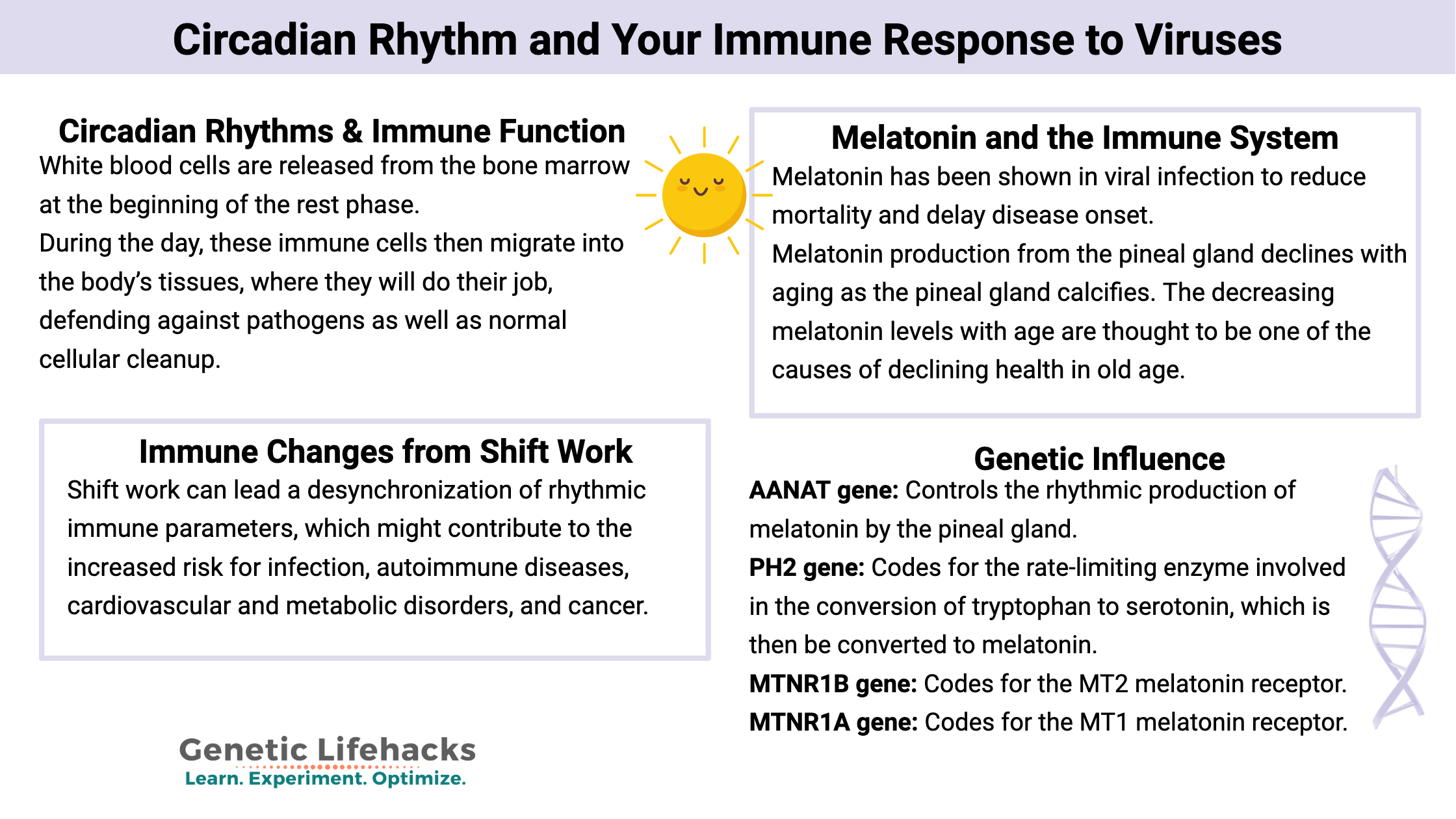

Researchers have found an innate circadian rhythm to the production of macrophages, B-cells, and T-cells. White blood cells are released from the bone marrow at the beginning of the rest phase (night time for humans). This release leads to a peak serum circulation for these immune cells in the rest period.[ref] During the day, these immune cells then migrate into the body’s tissues, where they will do their job, defending against pathogens as well as normal cellular cleanup.[ref]

Cortisol levels, as well as inflammatory cytokines, peak during the beginning of the active phase (first thing in the morning).[ref]

You can see where I’m going here — the overnight period of rest (aka sleep) is vital for your body’s immune function the next day.

Not only is there a rhythm to the production of new white blood cells, but within the cells, there is also a circadian rhythm. T-cells, a type of white blood cell produced in the thymus, have a circadian rhythm within the cell. These oscillations are controlled in part by BMAL1, a core circadian clock gene.[ref] Macrophages also exhibit their own internal clock, which affects the production of cytokines in the cells.[ref]

So basically, there is a rhythm to when there are more circulating white blood cells in the body — plus, there is a rhythm within the cells as to when they have maximum cytokine production.

Let’s take herpes as an example…

That is one headline that I never thought I would write :-)

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Long Covid: Genetics Research, Root Causes, and Possible Solutions

References:

Anderson, George, et al. “Ebola Virus: Melatonin as a Readily Available Treatment Option.” Journal of Medical Virology, vol. 87, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. 537–43. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24130.

Benegiamo, Giorgia, et al. “Mutual Antagonism between Circadian Protein Period 2 and Hepatitis C Virus Replication in Hepatocytes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 4, Apr. 2013, p. e60527. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060527.

Carrillo-Vico, Antonio, et al. “Melatonin: Buffering the Immune System.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 14, no. 4, Apr. 2013, pp. 8638–83. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14048638.

Carvalho, Miguel F., and Davinder Gill. “Rotavirus Vaccine Efficacy: Current Status and Areas for Improvement.” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 15, no. 6, Sept. 2018, pp. 1237–50. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1520583.

Colunga Biancatelli, Ruben Manuel Luciano, et al. “Melatonin for the Treatment of Sepsis: The Scientific Rationale.” Journal of Thoracic Disease, vol. 12, no. Suppl 1, Feb. 2020, pp. S54–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.12.85.

Cuesta, Marc, et al. “Simulated Night Shift Disrupts Circadian Rhythms of Immune Functions in Humans.” Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), vol. 196, no. 6, Mar. 2016, pp. 2466–75. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1502422.

Dickmeis, Thomas. “Glucocorticoids and the Circadian Clock.” The Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 200, no. 1, Jan. 2009, pp. 3–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1677/JOE-08-0415.

Ehlers, Anna, et al. “BMAL1 LINKS THE CIRCADIAN CLOCK TO VIRAL AIRWAY PATHOLOGY AND ASTHMA PHENOTYPES.” Mucosal Immunology, vol. 11, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 97–111. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2017.24.

Favero, Gaia, et al. “Melatonin as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent Modulating Inflammasome Activation.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2017, 2017, p. 1835195. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1835195.

Guise, Amanda J., et al. “Histone Deacetylases in Herpesvirus Replication and Virus-Stimulated Host Defense.” Viruses, vol. 5, no. 7, June 2013, pp. 1607–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/v5071607.

Keller, Maren, et al. “A Circadian Clock in Macrophages Controls Inflammatory Immune Responses.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 106, no. 50, Dec. 2009, pp. 21407–12. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906361106.

Khan, Naushad Ahmad, et al. “Waterpipe Smoke and E-Cigarette Vapor Differentially Affect Circadian Molecular Clock Gene Expression in Mouse Lungs.” PloS One, vol. 14, no. 2, 2019, p. e0211645. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211645.

Long, Joanna E., et al. “Morning Vaccination Enhances Antibody Response over Afternoon Vaccination: A Cluster-Randomised Trial.” Vaccine, vol. 34, no. 24, May 2016, pp. 2679–85. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032.

Marfè, Gabriella, et al. “Involvement of FOXO Transcription Factors, TRAIL-FasL/Fas, and Sirtuin Proteins Family in Canine Coronavirus Type II-Induced Apoptosis.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 11, Nov. 2011, p. e27313. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027313.

Masood, Tariq, et al. “Circadian Rhythm of Serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D, Calcium and Phosphorus Levels in the Treatment and Management of Type-2 Diabetic Patients.” Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics, vol. 9, no. 1, Feb. 2015, pp. 70–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5582/ddt.2015.01002.

Münch, Mirjam, et al. “Blue-Enriched Morning Light as a Countermeasure to Light at the Wrong Time: Effects on Cognition, Sleepiness, Sleep, and Circadian Phase.” Neuropsychobiology, vol. 74, no. 4, 2016, pp. 207–18. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1159/000477093.

Nobis, Chloé C., et al. “The Circadian Clock of CD8 T Cells Modulates Their Early Response to Vaccination and the Rhythmicity of Related Signaling Pathways.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 116, no. 40, Oct. 2019, pp. 20077–86. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1905080116.

Scheiermann, Christoph, et al. “Circadian Control of the Immune System.” Nature Reviews. Immunology, vol. 13, no. 3, Mar. 2013, pp. 190–98. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3386.

Shechter, Ari, et al. “Blocking Nocturnal Blue Light for Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 96, Jan. 2018, pp. 196–202. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.015.

Spengler, C. M., and S. A. Shea. “Endogenous Circadian Rhythm of Pulmonary Function in Healthy Humans.” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 162, no. 3 Pt 1, Sept. 2000, pp. 1038–46. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911107.

Sundar, Isaac K., Tanveer Ahmad, et al. “Influenza A Virus-Dependent Remodeling of Pulmonary Clock Function in a Mouse Model Of.” Scientific Reports, vol. 4, Apr. 2015, p. 9927. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09927.

Sundar, Isaac K., Michael T. Sellix, et al. “Redox Regulation of Circadian Molecular Clock in Chronic Airway Diseases.” Free Radical Biology & Medicine, vol. 119, May 2018, pp. 121–28. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.10.383.

Tan, Dun-Xian, et al. “Ebola Virus Disease: Potential Use of Melatonin as a Treatment.” Journal of Pineal Research, vol. 57, no. 4, Nov. 2014, pp. 381–84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12186.

Yuan, Yinglin, et al. “A Tissue-Specific Rhythmic Recruitment Pattern of Leukocyte Subsets.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 11, 2020, p. 102. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00102.

Zhou, Yadi, et al. “Network-Based Drug Repurposing for Novel Coronavirus 2019-NCoV/SARS-CoV-2.” Cell Discovery, vol. 6, no. 1, Mar. 2020, pp. 1–18. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-020-0153-3.