Key takeaways:

~ Cystic fibrosis is caused by having two mutated copies of the CFTR gene.

~ Up to 3% of the population carries one copy of a mutation for cystic fibrosis.

~ Being a carrier of a single cystic fibrosis mutation increases the risk of several diseases, including pneumonia from respiratory viruses, pancreatitis, and male infertility.

~ Learn how to check your genetic raw data to see if you are a carrier for a cystic fibrosis mutation.

What is Cystic Fibrosis?

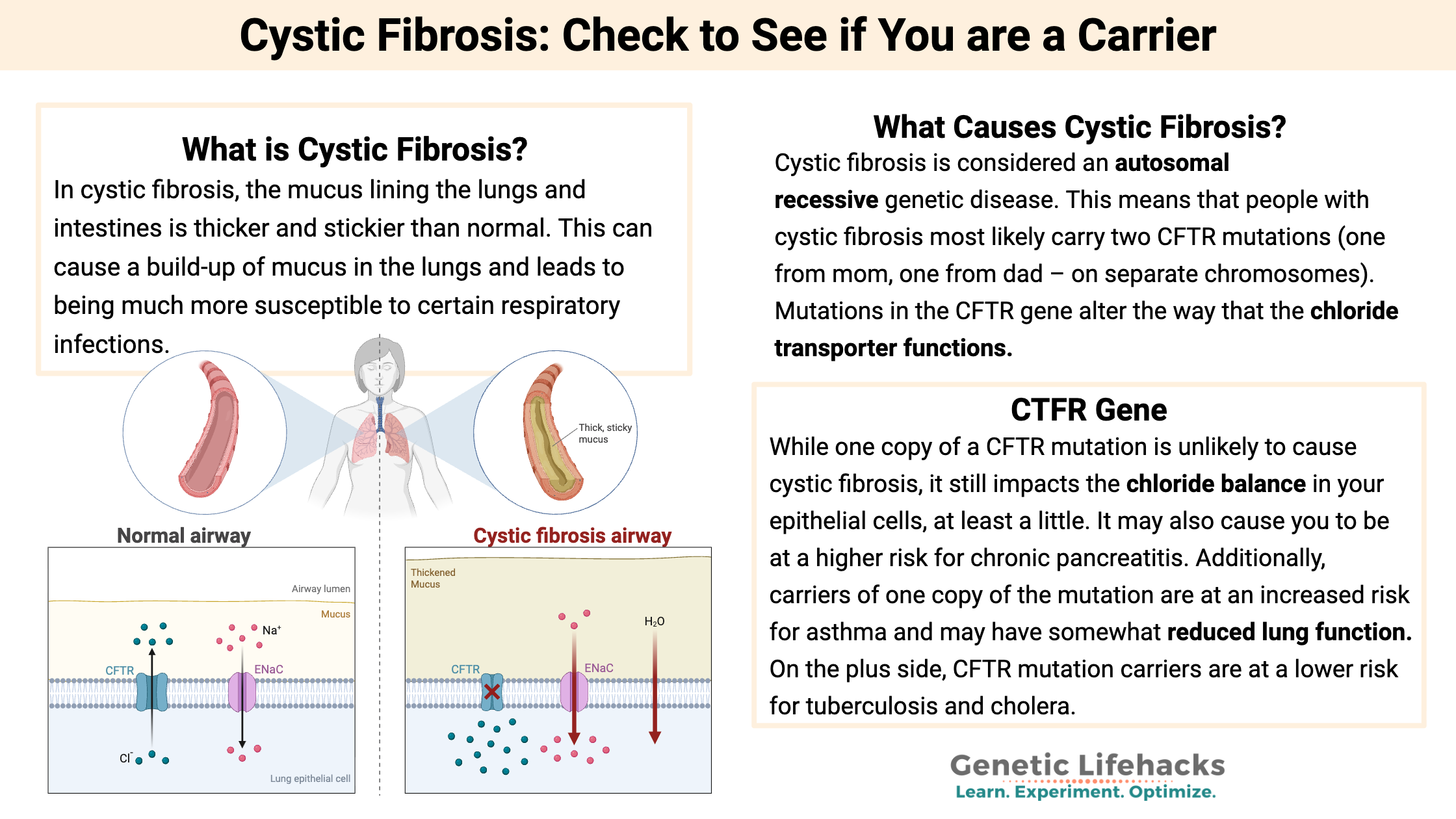

In cystic fibrosis, the mucus lining the lungs and intestines is thicker and stickier than normal. This can cause a build-up of mucus in the lungs and lead to being much more susceptible to certain respiratory infections.

What Causes Cystic Fibrosis?

The CFTR gene codes for a protein on the surface of epithelial cells, which make up your skin and line the intestines and lungs. This CFTR protein creates a channel on the cell membrane that regulates chloride ions moving in and out of cells. The CFTR transmembrane channel moves chloride (Cl-) and bicarbonate (HCO3-) out of the cell, which affects sodium ions coming into the cell.[ref]

Essentially, chloride movement via the CFTR transporter balances the amount of chloride and water in the cell and outside of the cell. The chloride ion is balanced with water, and the amount of chloride (and thus water) moved out of the cell thins out the mucous layer. This is important in the lungs because the mucus that lines the lungs needs to be thin enough. The movement of bicarbonate via the CFTR channel also impacts the pH of the mucous layer.[ref]

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disease:

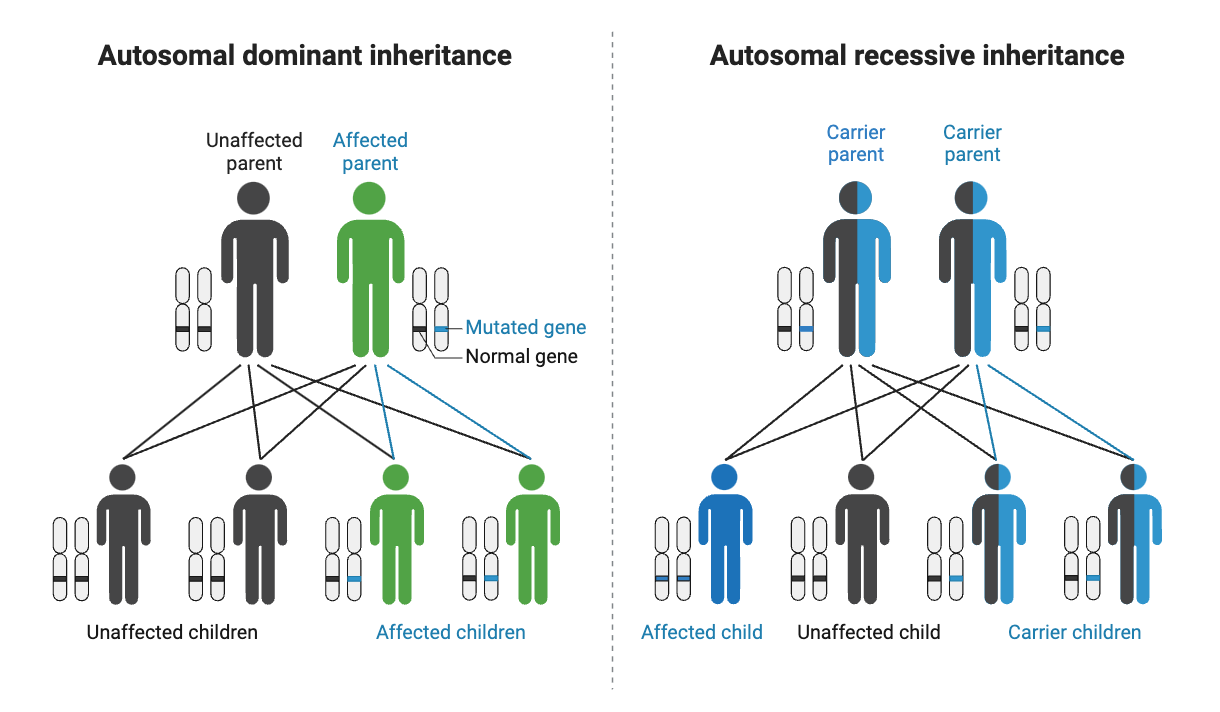

Cystic fibrosis is considered an autosomal recessive genetic disease. This means that people with cystic fibrosis most likely carry two CFTR mutations (one from mom, one from dad – on separate chromosomes).

Mutations in the CFTR gene alter the way that the chloride transporter functions. Different mutations can have different effects, and there are over 1,000 mutations identified in the CFTR gene. Thus, someone who carries two different CFTR mutations may have different symptoms and prognoses for the disease. The symptoms can vary from mild (or even undiagnosed) to severe.[ref]

The altered CFTR gene also increases the salt content in sweat. One diagnostic tool is to measure the salt content in sweat.[ref]

In addition to thicker lung mucus causing respiratory problems, the thicker mucous lining of the intestines can block the pancreas from releasing pancreatic enzymes. Individuals with cystic fibrosis have a high risk for pancreatic problems as well as digestive problems from a lack of pancreatic enzyme secretion.[ref]

For males with cystic fibrosis, thickened mucus often causes infertility.[ref]

Recent breakthroughs in cystic fibrosis treatments are helping to greatly extend the lifespan of patients. The ability to pinpoint the exact mutation is key. For example, people with the G511D mutation can get a specific new medication (Ivacaftor) that corrects the mutation. More drugs are now in clinical trials, as well.[ref][ref]

Carrying one copy of a CFTR mutation:

While one copy of a CFTR mutation is unlikely to cause cystic fibrosis, it still impacts the chloride balance in your epithelial cells, at least a little. It may also cause you to be at a higher risk for chronic pancreatitis. Additionally, carriers of one copy of the mutation are at an increased risk for asthma and may have somewhat reduced lung function, resulting in increased susceptibility to pneumonia and other lung disorders.[ref] Bile duct obstruction is also more common in carriers.[ref]

A recent study using data from almost 20,000 people who carried one copy of a CFTR mutation found that carriers were at a statistically increased risk for 57 different conditions, compared to a control group of about 100,000 people.[ref] Keep in mind this is just an increase in relative risk – just a little more likely than the average person to get the disease.

For example, carriers are at an increased risk of:

- Cachexia

- Failure to thrive

- Short stature

- Infants – meconium obstruction or peritonitis

- Male infertility (5-fold increased relative risk)

- Chronic pancreatitis and other pancreatic disorders

- Aspergillosis (fungal lung infections)

- Mycobacterial infections

- Respiratory infections

Increased risk of pneumonia (severe COVID-19 risk factor?):

A recent Vanderbilt University study found that people who carry one copy of a cystic fibrosis mutation are at a significantly increased risk for pneumonia, such as in influenza patients. The researchers also theorize that this increased pneumonia risk also applies to pneumonia in people who have COVID-19.[ref]

Note that studies on lung microbiota in COVID-19 patients with severe disease often show co-infections, such as Aspergillus and Klebsiella pneumoniae, in the lungs. It may be that the increased susceptibility to other pathogens has an impact on Covid mortality rates.[ref] Kids with cystic fibrosis usually have mild illness with COVID-19.[ref]

Benefits of carrying a cystic fibrosis mutation:

On the plus side, CFTR mutation carriers are at a lower risk for tuberculosis and cholera. Researchers theorize that the mutation is relatively common in certain population groups due to carriers of the mutation being more likely to survive cholera epidemics.[ref][ref]

When cholera swept through a village, a person with one copy of the CFTR mutation (and an altered intestinal mucosa) was more likely to survive, thus passing on the mutation to their offspring.

Cholera and tuberculosis have killed millions worldwide over the centuries, so even though there are many drawbacks to the CFTR mutation, the positive selection from not dying of TB or cholera is thought to keep this mutation in the population.

One more positive for CFTR carriers is that they may be at a lower risk for high blood pressure. A study of women who carried one copy of the CFTR mutation found that they were less likely to have high blood pressure after age 50 compared to an age-matched control group.[ref]

Cystic Fibrosis Genotype Report:

Two caveats first:

- The genetic raw data from 23andMe and AncestryDNA does not cover all of the 1,000+ CFTR mutations. For example, AncestryDNA raw data does not cover the Delta F508 mutation, which is one of the most common cystic fibrosis mutations. However, 23andMe does include it as i3000001.

- AncestryDNA and 23andMe do not guarantee clinical-grade accuracy of the data. There is always a chance of a false positive or negative, so you should always double-check with a clinical test before making a medical decision.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Genetic variants linked to COVID-19 severity

The question on everyone’s mind these days seems to be… Will I get COVID? If I do, will it be bad? The SARS-CoV-2 virus hits people so differently! While the majority of people are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, some people have severe cases that can result in death. Additionally, some have lingering symptoms that continue longer than normal for a seasonal respiratory virus.

TNF-alpha: Inflammation and Your Genes

Do you feel like you are always dealing with inflammation? Joint pain, food sensitivity, skin issues, gum disease, etc… It could be that your body is genetically gearing towards a higher inflammatory response due to high TNF-alpha levels.

Debbie Moon is a biologist, engineer, author, and the founder of Genetic Lifehacks where she has helped thousands of members understand how to apply genetics to their diet, lifestyle, and health decisions. With more than 10 years of experience translating complex genetic research into practical health strategies, Debbie holds a BS in engineering from Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson University. She combines an engineering mindset with a biological systems approach to explain how genetic differences impact your optimal health.