Have you ever had really bad jet lag and felt like you’ve been hit by a truck, disoriented, and unable to think clearly? Or stayed up late and feel off-kilter the next day?

For some, the heart of depression or mood disorders lies in circadian rhythm disruption. Fortunately, there are solutions that may help.

This article explains how circadian rhythm and genetics impact depression, and it wraps up with research-backed solutions. Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

Note: If you are under a doctor’s care, always talk to your doctor before making any changes.

Genetics and Depression:

Researchers use genetics to understand the biological pathways that drive mood disorders. By looking at genetic variants that are more common in people with depression, researchers can figure out the root cause of depression for individuals.

No, it isn’t all genetic. Genetic variants combine with environmental factors in mood disorders.

In fact, multiple genetic pathways can increase the susceptibility to mood disorders – this isn’t a one-size-fits-all problem. Multiple causes and many solutions.

One factor in mood disorders is a disruption of the circadian rhythm genes.

Read on to find out if this could be at the heart of the problem for you.

Background science: circadian rhythm genes

Before we get into depression and genetics, let’s dive into the science of how the circadian rhythm works.

At the core of biology for animals (and plants) are specific genes that code for a molecular circadian clock.

Think about it…for millions of years, plants and animals have had one sustaining, never changing factor: the sun comes up in the morning and sets at night. A 24-hour rhythm that never changes. (Until electric lights)

Our biological molecular clock, called the circadian clock, sets the rhythm of literally thousands of our genes over the course of about 24 hours.

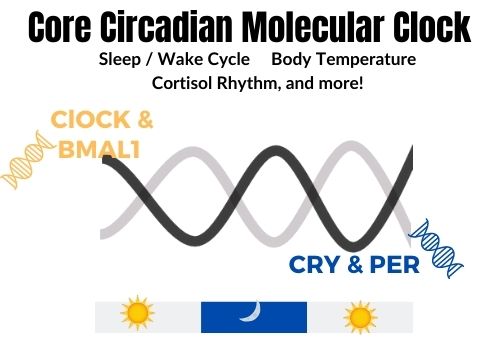

The molecular circadian clock is located in the hypothalamus region of the brain. It has some key genetic players: CLOCK and BMAL1 during the day and CRY and PER at night.

The levels of the CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins rise, triggering cellular events that need to occur during the day. Then at night, the levels of the CRY1/2 and PER1/2/3 proteins rise, signaling for night-time processes to take place.

Example: Your body produces enzymes during the day to break down the foods and toxins you consume or are exposed to. At night, cellular maintenance processes take place, getting you ready for the next day.

Here’s a quick visual for you showing the Circadian Clock Genes:

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm:

One of the first things that people think about in regard to circadian rhythm is the sleep/wake cycle. We naturally sleep and wake on about the same schedule every day – or we would if it weren’t for alarm clocks, work, and social engagements…

Sleep is essential for good mental health, but it is just one aspect of the circadian rhythm. So don’t get caught up thinking this is all about sleep. There is more to it!

Setting the circadian clock.

For humans, the average circadian clock runs about 15 minutes longer than 24 hours. But we aren’t all average, and the circadian period varies between a few minutes less than 24 hours to about a half-hour longer.[ref].

To keep us on track, the body has a built-in clock setting mechanism — exposure to light.

Imagine if your clock ran at about 24.5 hours instead of 24. Within a week, you would be about seven hours out of sync.

They’ve done studies with people kept in caves or bunkers, and with no outside light, this does happen.

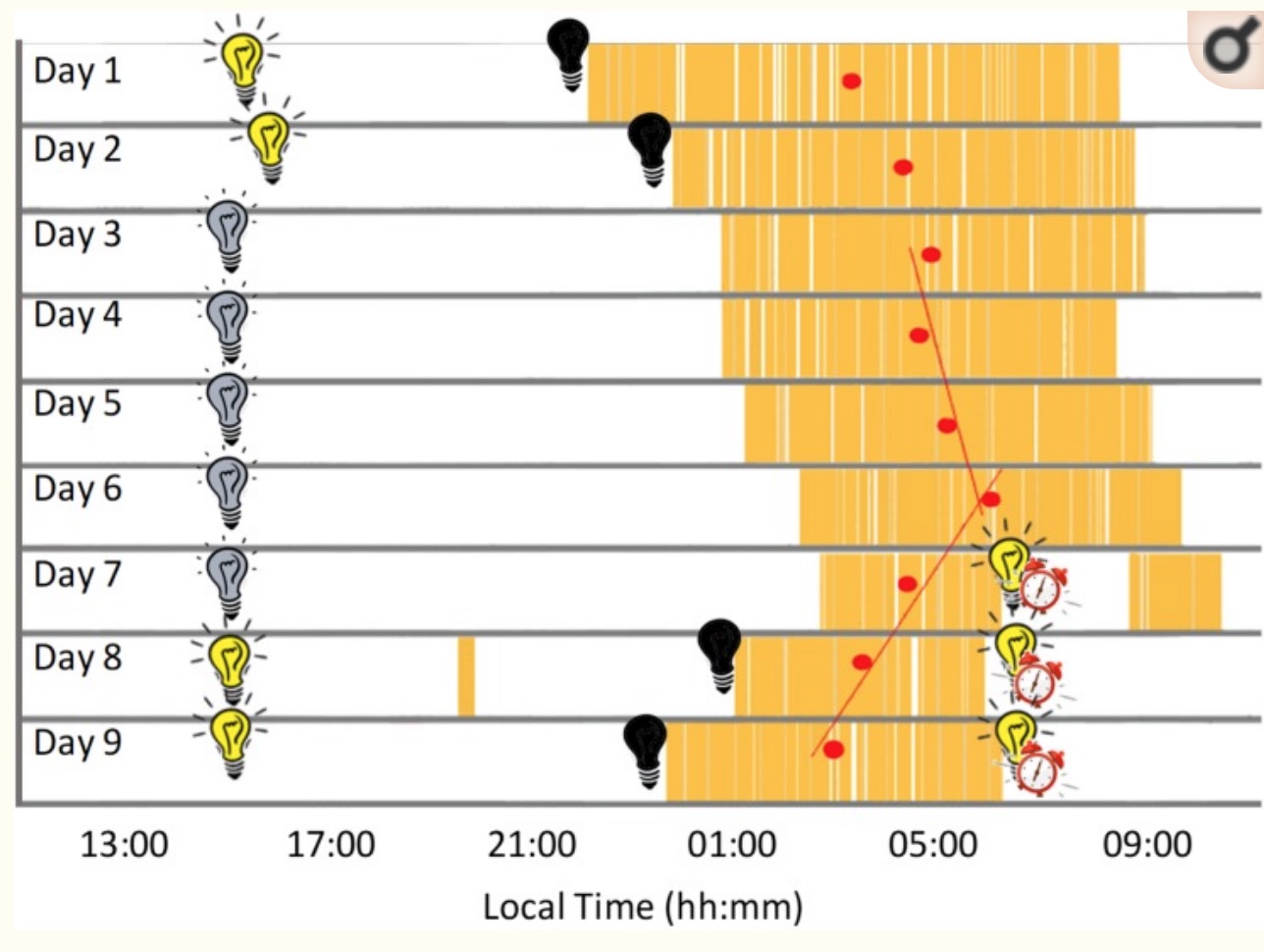

Below is a graph from a recent study where the participant stayed in a bunker for 9 days. The first two days and the last two days, he had lights available to turn on when he wanted. During days 3 through 7, a dim light was constantly turned on. As you can see, sleep timing (in yellow) and sleep duration changed a lot throughout the week. (creative commons image license) [ref]

While light is the main way the body resets the circadian clock, food timing and temperature changes can also make an impact.

What about melatonin?

Often referred to as the ‘sleep hormone’, melatonin levels rise at night when it is dark. It is a key molecule in circadian rhythm signaling.

Animal studies specifically show that melatonin is part of regulating some of the core clock genes. In fact, without melatonin, the PER1 gene doesn’t rise and fall rhythmically.[ref]

Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland in large amounts at night due to the lack of light. Exposure to artificial light at night significantly decreases overnight melatonin levels.

During the day, melatonin levels should be low – decreased by the bright light. In people with depression, research shows that melatonin levels are often higher than they should be during the day. This is possibly due to indoor lighting not suppressing the melatonin levels enough in an individual (hyposensitivity due to the low light).[ref]

Master clock and peripheral clocks:

To dig a little deeper here, your body’s core circadian rhythm is controlled in the part of the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

But other tissues in the body also have a circadian rhythm, termed peripheral clocks. For example, your liver has a circadian rhythm that is somewhat separate from the core circadian clock in the SCN. While independent, it does get synchronized with the core circadian clock. Everything needs to work together for the majority of the time.[ref]

Melatonin is one way the body synchronizes the central and peripheral clocks.

The rhythm of depression and anxiety:

Over the decades, there have been several theories about why circadian rhythm matters so much in depression and anxiety disorders.

Recent research shows that “psychiatric disorders might reflect a loss of synchronization between the external environment’s rhythms and the individual’s internal rhythms, leading to major problems of adaptation for the individual and the appearance of psychiatric disorders.“[ref]

When you are out of sync with your environment, it is disconcerting, to say the least.

Normally, your body temperature, cortisol levels, melatonin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone all rise and fall in a specific daily rhythm. Research shows that people with depression often have shifted daily rhythms – out of sync with the core circadian clock – for body temperature, cortisol, TSH, and melatonin.[ref][ref]

Circadian rhythm genes in mental illness:

Neuropsychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are tightly linked to the disruption of the core circadian rhythm genes. For example, in people with schizophrenia, cell studies show that there is a loss of circadian rhythm for the CRY1 and PER1 genes. Research also shows that there is a disruption in the CLOCK gene expression.[ref]

Researchers can manipulate the core circadian genes in animals – deleting genes or altering rhythms to see what happens. This gives us a lot of insight into what each circadian gene impacts.

For example, altering CRY protein levels in animals gives two different ends of the spectrum:

- When researchers knock out the CRY1/2 gene, the animals become anxious and are no longer active at the right time. Depression symptoms seemed unaffected, and sucrose consumption didn’t change. But their function when given cocaine was reduced and different from normal animals given cocaine.[ref]

- Alternatively, in animals that exhibited stress-induced depression-like helplessness, the researchers found higher than normal CRY expression. The researchers found that CRY was regulating midbrain dopamine levels.[ref]

In people without depression, CRY2 levels rise and fall rhythmically over the course of 24 hours. Sleep deprivation causes a big increase in CRY2 levels in healthy people. Strikingly, in people with depression, this pattern doesn’t happen. There is less of a CRY2 rhythm and no response to sleep deprivation.[ref]

In major depressive disorder, research also shows that there is a disruption of the phase and amplitude of the core circadian clock genes. In a landmark study in 2013, researchers compared circadian gene expression in the brains of people with depression to a control group. The results showed that depressed people had weaker cyclical clock gene patterns with shifted timing and “disrupted phase relationships between individual circadian genes.”[ref] While researchers had known for decades that there was a relationship between sleep, depression, and circadian rhythm, this study clearly showed that people with depression had a de-synchronization in the core circadian clock genes.

In young people with depression, a delay in the circadian phase (later onset of melatonin and later drop in core body temperature) correlates with increased severity of depression.[ref] It is important to note here that not all of the young people with depression had a delayed circadian phase–only about 40% did.

Circadian rhythm and seasonal depression:

Seasonal depression affects a lot of people living in northern climates in the winter months. It is defined as a period of fatigue, depression, and hopelessness – occurring with the changing of the seasons (usually late fall/winter).

Research shows that people with seasonal affective disorder (SAD) have a delay of about 1.5 hours in their melatonin production (compared to healthy controls). Along with the delay in melatonin, their body temperature rhythm was also delayed. Resetting this with bright light therapy in the morning shifted the melatonin rhythm back to normal and reversed depressive symptoms.[ref]

Depression medications that act on the circadian system:

Interestingly, many common antidepressant medications impact circadian rhythm.

- Citalopram is a commonly prescribed SSRI. It actually makes people more sensitive to light during the daytime. Thus, if you are stuck in lower-level indoor lighting, it makes you more sensitive to the light and suppresses melatonin during the day by almost 50% more. The researchers note that this may be why citalopram works well for some people and doesn’t work (or has the opposite effect) for others.[ref]

- A large-scale study by 23andMe on bupropion found that the efficacy of the drug depended on a genetic variant involved in circadian rhythm pathways.[ref]

- For treatment-resistant depression, there are two methods that doctors can use that may immediately change mood: sleep deprivation (resetting of the clock) and ketamine. Low doses of IV ketamine are very effective for some people with depression. It is not FDA-approved for this usage in the US at this time, but some clinics offer it. Ketamine has recently been shown to act on depression via altering BDNF and increasing slow-wave sleep.[ref]

- Fluoxetine has been shown in animal studies to normalize ‘light-induced’ circadian disruption. It does this through increased PER2 and PER3 levels.[ref]

- Agomelatine is a synthetic version of melatonin that is prescribed as an atypical antidepressant.[ref]

Definitions to keep us on track:

Depression is kind of a catch-all term, with specific types defined by doctors. Here are several that will be referred to throughout this article.

- Dysthymia is a type of depression with a long-term loss of interest in life – low energy, low appetite, hopelessness, and poor concentration.

- Bipolar disorder, also called manic-depressive disorder, is characterized by episodes of depression (low energy, loss of motivation) and episodes of mania (high energy, reduced sleep, possibly out of touch with reality).

- Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a period of depressed mood, decreased motivation, and cognitive impairment.[ref]

Circadian Rhythm Genotype Report:

The following circadian gene variants are linked with depression. Keep in mind these are just the variants that have been identified so far by researchers, and this only represents the variants found in 23andMe/AncestryDNA. (In other words – there are other variants, both known and unknown, that impact circadian rhythm and depression risk.)

Not a member? Join here. Membership lets you see your data right in each article and also gives you access to the member’s only information in the Lifehacks sections.

CRY1 gene: codes for a core circadian clock gene (partners with PER gene)

Check your genetic data for rs10861688 (AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/T: increased risk of depression (specifically dysthymia), increased depressive episodes in bipolar disorder

- T/T: increased risk of depression (specifically dysthymia)[ref]; increased depressive episodes in bipolar disorder[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs10861688 is —.

CRY2 gene: This core circadian clock protein also partners with the PER proteins. People with seasonal depression, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder have lower levels of CRY2.[ref]

Check your genetic data for rs10838524 (AncestryDNA):

- A/A: typical

- A/G: increased risk of depression (specifically dysthymia)

- G/G: increased risk of depression (specifically dysthymia)[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs10838524 is —.

PER2 gene: codes for a core circadian clock gene (partners with CRY proteins)

Check your genetic data for rs934945 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/T: increased risk of severity in psychotic disorders

- T/T: increased risk of severity in psychotic disorders[ref]

*note that this is given in the plus orientation to match your genetic data.

Members: Your genotype for rs934945 is —.

PER3 gene: codes for a core circadian clock protein (partners with CRY proteins)

Check your genetic data for rs139315125 (23andMe v5):

- A/A: typical

- A/G: increased risk of depression, delayed sleep disorder[ref], lengthened circadian period when not reset by light[ref]

- G/G: increased risk of depression, delayed sleep disorder, lengthened circadian period when not reset by light[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs139315125 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs228697 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/G: increased risk of depression, increased anxiety

- G/G: increased risk of depression[ref], increased anxiety[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs228697 is —.

NPAS2 gene: codes for a paralogous (similar) protein to CLOCK that can bind with BMAL1

Check your genetic data for rs11123857 (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: typical

- A/G: increased risk of depressive disorders, bipolar disorder

- G/G: increased risk of depressive disorders, bipolar disorder[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs11123857 is —.

NR1D1 gene: codes for REV-ERBα, which is part of a feedback control loop for the production of BMAL1[ref]

Check your genetic data for rs2314339 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/T: increased risk of depression, bipolar disorder, lithium less likely to work for bipolar

- T/T: increased risk of depression, bipolar disorder[ref][ref], lithium less likely to work for bipolar patients[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs2314339 is —.

OPN4 gene: codes for the melanopsin receptor in the retina of the eye that senses light and sets the circadian rhythm

Check your genetic data for rs2675703 (23andMe v5; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/T: increased risk of seasonal depression, sensitivity to low light levels

- T/T: significantly increased risk of seasonal depression; sensitivity to lower light levels[ref][ref] linked to increased risk of chronic insomnia[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs2675703 is —.

Lifehacks for changing circadian rhythm:

Let me reiterate: this information is for educational purposes. If you are under a doctor’s care for a mood disorder, please check with your doctor before making any changes.

1) Shifting the Circadian Clock with light

The rest of this article is for Genetic Lifehacks members only. Consider joining today to see the rest of this article.

Related Articles and Topics:

Is inflammation causing your depression and anxiety?

Research over the past two decades clearly shows a causal link between increased inflammatory markers and depression. Genetic variants in the inflammatory-related genes can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.

Melatonin: Key to Health and Longevity

It seems like everything that I’ve written about lately has a common thread: melatonin. When I started weaving together all those melatonin threads, a big picture was revealed. You could say it is a… tapestry of health.

Using your genetic data to solve sleep problems

A good night’s sleep is invaluable – priceless, even – but so many people know the frustration of not being able to sleep well regularly. Not getting enough quality sleep can lead to many chronic diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, dementia, and heart disease. Yes, sleep really is that important!

DEC2 Gene: Short Sleep Mutation

A rare mutation in the DEC2 gene causes some people to need about an hour and a half less sleep each night. People with the mutation average 6 to 6.5 hours of sleep.