Key takeaways:

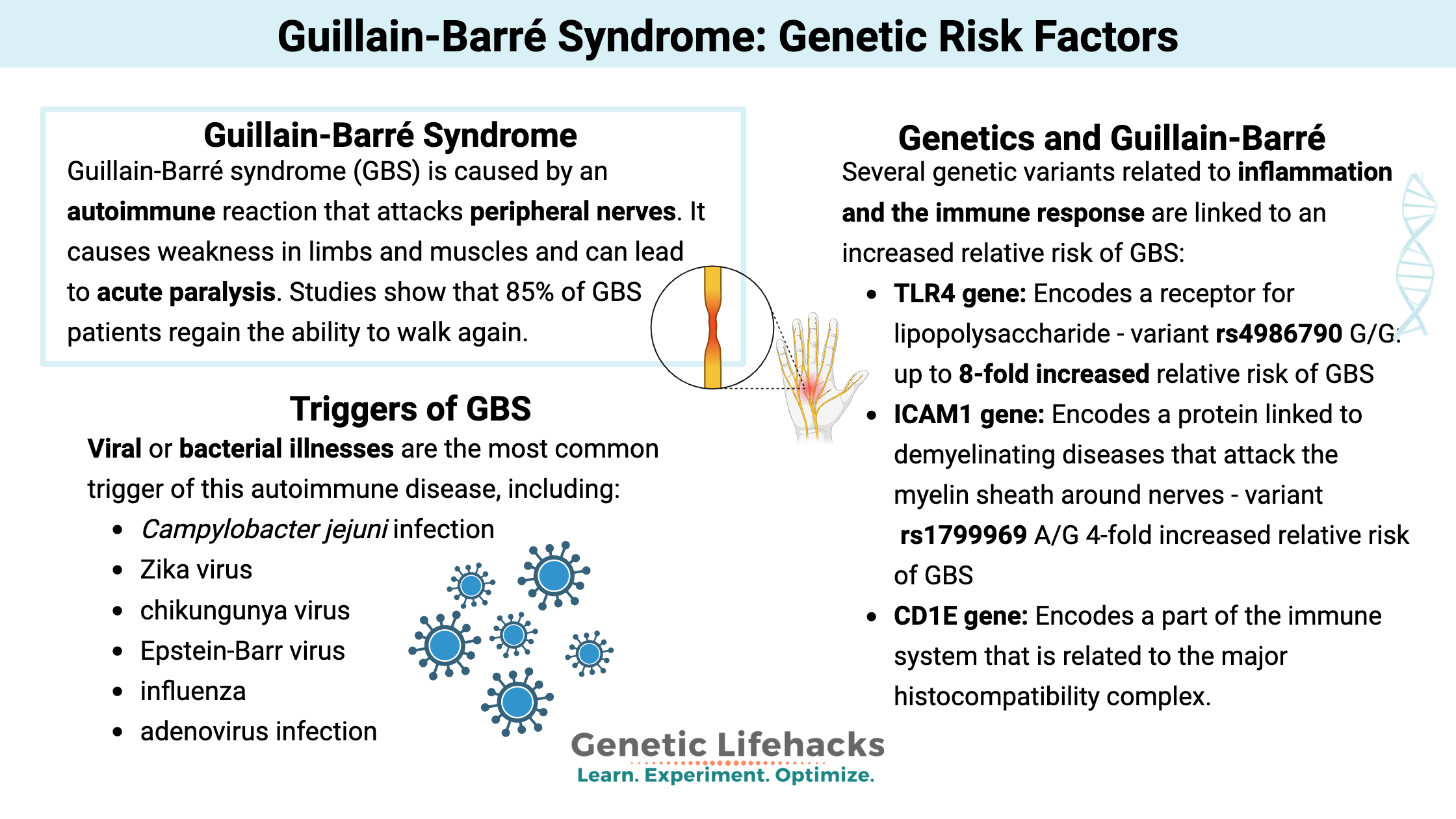

~ Guillain-Barré syndrome causes weakness or paralysis in the limbs.

~ It is caused by an autoimmune reaction attacking the peripheral nerves.

~ Genetic variants increase the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome in conjunction with immune system triggers.

This article dives into the research on Guillain-Barré syndrome, explaining the course of the disease, and covering the genetic variants that increase the relative risk of this serious autoimmune disease.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.What is Guillain-Barré syndrome?

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an autoimmune disease that causes weakness in limbs and muscles.

Referred to as ‘acute flaccid paralysis’, people with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) have neuromuscular weakness, usually starting in the feet and legs, that can spread, causing paralysis throughout the body.

Guillain-Barré syndrome is caused by an autoimmune reaction that attacks peripheral nerves, leading to demyelination or axonal damage. For some patients, it is autoreactive T cells targeting myelin antigens that cause the demylination.[ref][ref]

This is an autoimmune disease that usually resolves eventually and doesn’t return. The peak paralysis is usually reached within 4 to 6 weeks.[ref]

Many GBS patients require extended hospitalization. Mechanical ventilation may be required if the paralysis impacts breathing. This occurs in about 30% of Guillain-Barré syndrome patients. Often, a feeding tube is needed due to problems with swallowing.

Studies show that 85% of GBS patients regain the ability to walk again. The mortality rate is about 5%, and 20% of patients have continued significant disability from Guillain-Barré.[ref]

The autoimmune reaction in GBS involves antiganglioside antibodies, which attack gangliosides that are necessary for neuronal plasticity. These molecules are similar to sialic acids found in viruses and thus may be attacked after the immune system is activated by a virus.[ref] The autoimmune attack on the peripheral nerves can lead to nerve death or the inability of the nerve to transmit a signal.

How common is Guillain-Barré syndrome?

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an uncommon disease. Around the world, prevalence ranges from <1 to 2 in 100,000 people per year.[ref]

Known triggers of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) include:[ref]

- Campylobacter jejuni infection[ref]

- Zika virus

- chikungunya virus

- Epstein-Barr virus

- influenza[ref]

- adenovirus infection[ref][ref]

- the flu vaccine (especially the early vaccines in the 90s)[ref]

- Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine[ref]

- other adenovirus vector vaccines[ref][ref]

Viral or bacterial illnesses are the most common trigger of this autoimmune disease. About 70% of patients have a viral or bacterial illness within 1 to 6 weeks before the onset of GBS.[ref]

One study in India found that two-thirds of the Guillain-Barré syndrome patients had an identifiable recent infection, such as the chikungunya virus (16%) or Campylobacter jejuni (5%).[ref]

Obviously, not everyone who gets sick from a virus or bacteria will get Guillain-Barré.

- About 1 in 1,000 people infected with Campylobacter jejuni, a bacteria in poultry that causes food poisoning, will end up with GBS.[ref]

- About 1 in 500 people infected with the Zika virus get GBS.[ref]

Clinical outcomes of Guillain-Barré syndrome:

A study of 156 GBS patients showed that common symptoms include weakness, paralysis, sensory symptoms, facial paralysis, problems swallowing, and eye problems. About a quarter of the patients were on mechanical ventilation because the muscles for breathing weren’t working correctly. In this study group, about half of the patients regained the ability to walk after nine months.[ref]

Another study found that all Guillain-Barré patients included in the study had limb weakness in both arms and legs and decreased reflexes in the arms and legs that persisted even in follow-up.[ref]

A study of 45 Guillain-Barré syndrome patients in a Swiss hospital from 2010-2018 showed that IL-8, an inflammatory cytokine, was elevated in patients. This may be a way to differentiate GBS from other demyelinating neuropathies.[ref]

Guillain-Barré syndrome and vaccines:

I know this is a touchy topic, and I want to encourage you to search the VAERS database for the information yourself. The VAERS database contains reports from doctors and people in the United States who have reacted to any vaccine. Specific search terms related to paralysis, demyelination, autoimmune reactions, or Guillain-Barre hospitalizations will give you the best results.

Keep in mind that correlation doesn’t automatically mean causation.

- An adenovirus vaccine given to military personnel starting in 2011 reported Guillain-Barré as an adverse event.[ref]

- Historically, flu vaccines have been linked to GBS. More recent flu vaccines, though, might increase the cases of GBS by 1 case in 1,000,000 vaccines administered.[ref][ref]

- No increase in Guillain-Barré syndrome has been seen after vaccination against “hepatitis B, influenza, hepatitis A, varicella, rabies, polio(live), diphtheria, pertussis(acellular), tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella, Japanese Encephalitis, and meningitis”.[ref]

- A few studies have reported slight increases in the GBS rate in young women after the HPV vaccine.[ref]

- The FDA also includes a warning of an increased risk of GBS after the shingles vaccine (Shingrix). The warning is based on a statistical signal of the increase in GBS cases according to Medicare claims.[ref]

- J&J COVID-19 vaccine: The FDA now includes a warning with the Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine regarding the increased risk of GBS. It is a rare side effect, but the frequency is enough to prompt an FDA warning.[ref][article] The Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine is an adenovirus vector that delivers the spike protein as a vaccine.

- A 2024 meta-analysis found that there 1.25 cases of GBS per million Covid vaccine doses.[ref]

Genetics and Guillain-Barre:

Researchers have found that several genetic variants related to inflammation and the immune response are linked to an increased relative risk of Guillain-Barre Syndrome – in conjunction with the immune system trigger.

Important note about relative risk:

When a disease is rare, a big increase in relative risk may not mean much. For example, if the normal annual rate of GBS is 1 in 100,000 people, quadrupling that risk would mean a risk of 4 in 100,000.

Even if a vaccine is causing a 10-fold increase in GBS cases and you have a genetic risk variant, your odds of getting Guillain-Barre syndrome are still really slim. Please take this information as being educational and interesting rather than an indication of whether you should take any particular action.

Guillain-Barre Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

There isn’t a medication, lifestyle change, or supplement for GBS.

Instead, early treatment in the hospital with plasma exchange or IV immunoglobulin seems to shorten the duration of hospitalization.[ref]

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

References: