Key takeaways:

~ PCOS – polycystic ovary syndrome – is a systemic disorder that can cause menstrual irregularities, altered hormone levels, weight gain, and ovarian cysts.

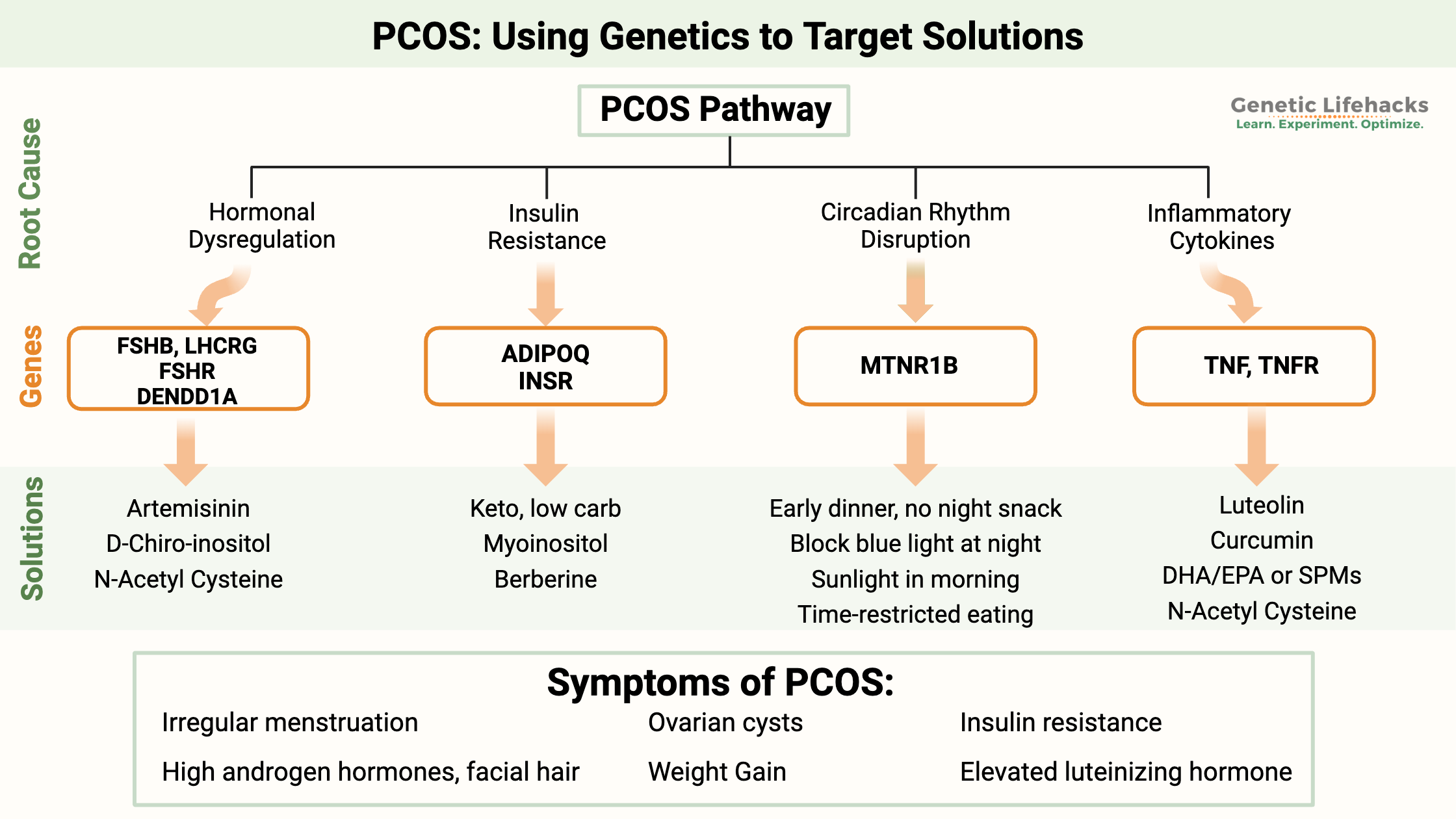

~ Multiple biological pathways can cause PCOS, including metabolic causes, hormonal dysregulation, or circadian rhythm-driven changes.

~ Understanding your genetic susceptibility may help you to target the right root cause.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

Getting to the root cause of PCOS:

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder that causes an increase in androgen hormone production in women. It affects 5 -18% of premenopausal women.[ref]

Genetics plays a large role in whether you are likely to have PCOS. No single gene causes PCOS, but there are genetic variants in several hormonal pathways that increase the risk for it. The genetic variants come together to increase susceptibility to PCOS – along with your lifestyle, diet, and environment.

Researchers estimate that PCOS is about 70% heritable.[ref] Understanding which genetic variants you carry may help you figure out the most effective way for you to manage your PCOS.

Symptoms of PCOS:

PCOS symptoms include:[ref]

- Irregular menstrual cycles

- High androgen hormones, sometimes leading to facial hair

- Possible presence of cysts in the ovaries

- Weight gain

- Insulin resistance

- Elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) levels.

The excess of androgen hormones may cause facial or back hair as well as male pattern baldness. Skin problems include hormonal acne.

PCOS is a ‘syndrome’, meaning that not all symptoms have to be present to have PCOS. Also, not everyone with PCOS has ovarian cysts — and not everyone with ovarian cysts has PCOS.[ref]

Root Causes of PCOS:

Let’s take a deep dive into what causes PCOS… and then look at your specific genetic susceptibility.

The physiological changes that we will look at include:

- Hormone dysregulation

- Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

- Circadian rhythm dysregulation

- Elevated inflammatory cytokines

While I’m breaking the research into different pathways, keep in mind that there is overlap between the pathways. More than one is likely to apply.

PCOS Pathway 1: Hormonal Dysregulation

Before diving into what goes wrong with PCOS, let’s first look at the hormonal processes that generally go on during a menstrual cycle.

The start of menstruation (your period) is considered the beginning of the menstrual cycle. Estrogen and progesterone levels are both low at this point. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) rises a bit, causing the development of a new follicle (containing an egg) in the ovary. The follicle produces estrogen, causing estrogen to rise over the next week.

Around days 12 – 14, ovulation occurs, releasing the egg. During ovulation, the pituitary gland releases luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH at higher levels. This spike in LH and FSH hormone levels coincides with a fall in estrogen levels and an increase in progesterone. The follicle that has released the egg cell will form a corpus luteum, a hormone-secreting structure that produces high levels of progesterone.

What does your body need to make all these reproductive hormones? The molecular basis for these steroid hormones is cholesterol, which is converted into pregnenolone, which is the precursor for other hormones.

There are two ways that pregnenolone can be converted into other hormones. The enzyme CYP17A1 can eventually convert pregnenolone into DHEA. Alternatively, the enzyme 3B-HSD can convert pregnenolone into progesterone. DHEA can then be converted into testosterone or other androgens — or it can convert to estrone and other estrogens.

Reproductive phenotype: For some women, hormonal changes are driving PCOS.[ref] Researchers refer to this as the reproductive phenotype.

For others, hormonal changes may not be the driving factor in PCOS, and instead, the following pathways may be more important.

PCOS Pathway 2: Insulin resistance and androgen hormone production

Women with PCOS often have problems with insulin resistance and higher blood glucose levels. These metabolic changes can be a driving factor in the hormonal changes seen in PCOS. [ref]

Insulin increases the production of androgens in women. For this reason, women’s increased testosterone levels show associations with insulin resistance. The system works both ways – giving women testosterone can increase insulin resistance. These hormones are all interrelated. In the ovaries, insulin stimulates the production of testosterone.[ref][ref]

Androgen hormones in women usually convert to estrogen. Higher estrogen levels feed back to the pituitary gland, causing an increase in LH (luteinizing hormone) during ovulation.[ref]

Thus, when levels of androgen hormones are too high and not appropriately converted to estrogen, it interferes with ovulation or the release of the egg. It causes what looks like cysts in the ovaries when the immature egg follicles aren’t released.

Mendelian randomization studies can help to understand whether a genetic pathway is causal for a condition. In PCOS, there is a strong genetic link between BCAA (branched-chain amino acid) levels, insulin resistance, and the cause of PCOS.[ref]

Related article: Insulin resistance, BCAAs, and Genetics

About 20 – 30% of women with PCOS have high DHEA levels. DHEA is a precursor for androgens and estrogens.[ref]

PCOS Pathway 3: Circadian rhythm disruption as a cause of PCOS:

Recent studies show a significant link between disruptions in circadian rhythm and the development of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).[ref]

Animal studies specifically show causation: disrupting circadian rhythm causes the same hormone changes as are seen in PCOS. [ref][ref]

For decades it was known that altering circadian rhythm could alter insulin sensitivity and androgen production. The latest research, however, goes a step further. By manipulating light exposure, scientists demonstrated that changes in circadian clock genes could directly influence the hormonal imbalances seen in PCOS. The researchers used changes in light to show that alterations to the circadian clock genes caused the downstream effects on the hormones involved in PCOS.

A Brief Overview of Circadian Rhythm:

Circadian rhythm – your body’s internal clock – orchestrates a 24-hour cycle of biological processes. It’s widely recognized for regulating the sleep-wake cycle, but its influence extends far beyond sleep, impacting various metabolic and cellular functions. This rhythm, dictated largely by light exposure, ensures that certain bodily processes occur optimally during the day or night.

Circadian Rhythm Disruption: A Modern Health Challenge:

The disturbance of this natural rhythm has been linked to several chronic conditions, such as obesity, heart disease, and dementia. If you’ve ever experienced jet lag when traveling, you know how circadian rhythm disruption can leave our bodies feeling out of sync. However, it isn’t just when traveling that circadian rhythm can get out of sync. Everyday examples include staying up late under bright lights, leading to what is termed ‘social jet lag.’

The body’s circadian clock is driving the rise and fall of some key proteins and your hormones — and these oscillations are synchronized by light. Exposure to light at night (screens, bright overhead lights, etc) causes a disruption in circadian rhythm, altering when your hormone levels rise and fall. This means that lifestyle adjustments, particularly in managing light exposure at night, could be very important for some people with PCOS.

PCOS Pathway 4: Inflammation

In PCOS, research shows that inflammatory markers are higher than normal. Research shows increased levels of TNF-alpha, C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 18 (IL-18), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) in the PCOS women compared with age- and BMI-matched volunteers.[ref]

Genetic research points to elevated inflammation, specifically increased TNF levels, as playing a causal role in PCOS. This could be due to a hyperinflammatory state in the uterus and ovaries. Excess ROS and oxidative stress then play a role in menstrual irregularities.[ref]

Alternatively, the elevated inflammatory cytokines could be, at least in part, due to obesity. However, not all obese women have elevated inflammation, and not all women with PCOS are obese. So obesity isn’t the only cause of elevated inflammation.

Other considerations with PCOS: Environmental contamination, diet, and thyroid function

While there are four biological pathways that can be involved in the root cause of PCOS, let’s also look at the environmental factors that may initiate the changes.

Microplastics:

Microplastics are the microscopic bits of different types of plastic that are ubiquitous now in our food, water, and air. We all are exposed to microplastics on a daily basis. The plastic particles can secrete endocrine-disrupting hormones, but more importantly, the particles themselves are found in the ovaries.

Studies in animals show that microplastics can induce PCOS-like lesions and cause a lack of ovulation. In mice, exposure to polystyrene microplastics reduces oocyte maturation, and another study showed altered testosterone levels in females. In humans, a pre-print study (2024) shows that 14 out of 18 samples of follicular fluid contained microplastic particles with an average size of less than 5µm and a concentration of 2191 p/ml. The samples were from healthy women undergoing fertility treatment.[ref][ref]

Is PCOS reversible with diet?

Insulin resistance is at the heart of PCOS for many women, and your diet plays a huge role in insulin resistance. There are a lot of clinicians who claim the right diet is a solution for PCOS symptoms. Most focus on healthy, whole foods, and some claim a ketogenic diet works.[article][article] However, other medical-based websites claim that all you can do is manage the symptoms of PCOS and that there is no cure.[article]

There’s quite a bit of clinical research on what works for PCOS, which I’ve included in the Lifehacks section below. The solutions there integrate genetic variants with research on diet, supplements, and exercise so that you can target the right pathway.

Weight loss without dietary changes may not always help. Research points to weight gain being caused by PCOS instead of obesity as a cause of PCOS. Thus, reversing PCOS may lead to weight loss rather than weight loss alone reversing PCOS.[ref]

With the strong link to insulin resistance, aligning your diet to decrease IR may give you the best results in the long run.

Related article: Insulin Resistance and Genetics: Finding the Root Cause

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and PCOS:

Researchers have found autoimmune thyroid diseases, such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, at much greater levels in women with PCOS. Thus, if you or your doctor suspects that you have a thyroid problem, it is recommended to also test for autoimmune thyroid antibodies.[ref]

Related article: Thyroid hormones and your genes

Pregnancy and PCOS:

Getting pregnant can be a problem with PCOS. Essentially, women with PCOS are more likely to have problems with ovulation, which is a common cause of infertility. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is a common solution for PCOS infertility.[ref] There are also medications that your doctor can prescribe that alter your hormones at the right time in your cycle.

Overall statistics are hard to come by regarding the percentage of women with PCOS and infertility. Larger population studies point to women with PCOS being more likely to have fewer children but having similar overall fertility rates when looking only at women with 1 – 2 children.[ref] Thus, getting pregnant with PCOS is entirely possible, but it may take a little more time.

Genetics and PCOS:

Genetic variants play a significant role in PCOS. Studies suggest that about 70% of PCOS cases have a hereditary component, indicating a strong genetic influence in its development.

PCOS is considered an ‘evolutionary paradox’ since it is common (10% of the population), highly heritable, and can also cause infertility.

Scientists want to know why the genetic variants involved in PCOS have continued to be passed on to a large part of the population – especially since evolutionary theory says that it should be weeded out. Some theories on this include that women with PCOS are more ‘metabolically thrifty‘ and likely to live through a famine. Others theorize that women who only have a few children are better mothers, and the children are more likely to survive.

Evolutionary theorizing aside, understanding which genetic variants you carry may help you to find the right solution for your PCOS symptoms.

PCOS Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks

If you are under a doctor’s care, be sure to talk with your doctor before making any changes to supplements or diet.

The solutions below are grouped into pathways – circadian rhythm, inflammation, hormonal dysregulation, and insulin resistance. But you may find that addressing all the pathways is important for reversing PCOS and that they are intertwined. For example, getting your circadian rhythm on track may help with hormone regulation and insulin resistance. Tamping down inflammation may help with hormone regulation and also may increase sleep quality and help circadian rhythm.

PCOS Pathway: Circadian rhythm

Circadian rhythm disruption may be at the heart of PCOS for many women. Circadian rhythm disruption may affect both insulin sensitivity and androgen hormone production. [ref]

The question is: What can you do in our modern world to get your circadian rhythm back on track – without getting rid of electronics and electric lights in the evening?

- Supplementing with melatonin for six months decreased androgen levels and increased FSH levels in women with PCOS.[ref]

- One huge thing you can do to increase melatonin naturally and get your circadian rhythm on track is to block out blue light at night.

- Getting outside as early as possible in the morning will help set your circadian rhythm. And sunlight exposure during the day has been shown to help boost melatonin production the next night.

- Women with PCOS are twice as likely to have sleep disturbances, and LH levels are related to changes in the sleep/wake cycle. Some researchers theorize that circadian rhythm disturbances are part of the pathogenesis of PCOS.[ref][ref]

- Eating earlier and not snacking after dinner should help insulin resistance if you carry the MTNR1B variant.

PCOS Pathway: Inflammation and the resolution of inflammation

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

BPA and BPS: How Your Genes Influence Bisphenol Detoxification

References:

Balen, Adam H., and Anthony J. Rutherford. “Managing Anovulatory Infertility and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” BMJ, vol. 335, no. 7621, Sept. 2007, pp. 663–66. www.bmj.com, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.462303.80.

Capalbo, A., et al. “The 312N Variant of the Luteinizing Hormone/Choriogonadotropin Receptor Gene (LHCGR) Confers up to 2·7-Fold Increased Risk of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in a Sardinian Population.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 77, no. 1, July 2012, pp. 113–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04372.x.

Corbett, Stephen, and Laure Morin-Papunen. “The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Recent Human Evolution.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 373, no. 1–2, July 2013, pp. 39–50. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.01.001.

Corbould, A. “Effects of Androgens on Insulin Action in Women: Is Androgen Excess a Component of Female Metabolic Syndrome?” Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, vol. 24, no. 7, Oct. 2008, pp. 520–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.872.

Day, Felix R., et al. “Causal Mechanisms and Balancing Selection Inferred from Genetic Associations with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Nature Communications, vol. 6, Sept. 2015, p. 8464. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9464.

De Sousa, Sunita M. C., and Robert J. Norman. “Metabolic Syndrome, Diet and Exercise.” Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 37, Nov. 2016, pp. 140–51. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.01.006.

Fernandez, Renae C., et al. “Sleep Disturbances in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Prevalence, Pathophysiology, Impact and Management Strategies.” Nature and Science of Sleep, vol. 10, 2018, pp. 45–64. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S127475.

Furat Rencber, Selenay, et al. “Effect of Resveratrol and Metformin on Ovarian Reserve and Ultrastructure in PCOS: An Experimental Study.” Journal of Ovarian Research, vol. 11, no. 1, June 2018, p. 55. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0427-7.

Gao, Jing, et al. “The Association of DENND1A Gene Polymorphisms and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 294, no. 5, Nov. 2016, pp. 1073–80. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4159-x.

Ghowsi, Mahnaz, et al. “The Effect of Resveratrol on Oxidative Stress in the Liver and Serum of a Rat Model of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Experimental Study.” International Journal of Reproductive Biomedicine, vol. 16, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 149–58.

Goodarzi, Mark O., et al. “DHEA, DHEAS and PCOS.” The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, vol. 145, Jan. 2015, pp. 213–25. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.06.003.

Goodarzi, Mark O, et al. “Replication of Association of DENND1A and THADA Variants with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in European Cohorts.” Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 49, no. 2, Feb. 2012, pp. 90–95. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100427.

Gu, Bon-Hee, et al. “Genetic Variations of Follicle Stimulating Hormone Receptor Are Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” International Journal of Molecular Medicine, vol. 26, no. 1, July 2010, pp. 107–12. www.spandidos-publications.com, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm_00000441.

Hossein Rashidi, Batool, et al. “The Association Between Bisphenol A and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Case-Control Study.” Acta Medica Iranica, vol. 55, no. 12, Dec. 2017, pp. 759–64.

“How to Reverse PCOS Naturally [Affects, Supplements & Keto Diet].” Ruled Me, 11 Sept. 2017, https://www.ruled.me/reverse-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos-naturally/.

Ismail, Alaa M., et al. “Adding L-Carnitine to Clomiphene Resistant PCOS Women Improves the Quality of Ovulation and the Pregnancy Rate. A Randomized Clinical Trial.” European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, vol. 180, Sept. 2014, pp. 148–52. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.06.008.

Jamilian, Hamidreza, et al. “Oral Carnitine Supplementation Influences Mental Health Parameters and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Gynecological Endocrinology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 33, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 442–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2017.1290071.

Jamilian, Mehri, et al. “Metabolic Response to Selenium Supplementation in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 82, no. 6, June 2015, pp. 885–91. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.12699.

Khan, Muhammad Jaseem, et al. “Genetic Basis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Current Perspectives.” The Application of Clinical Genetics, vol. 12, Dec. 2019, pp. 249–60. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S200341.

Kim, Jin Ju, et al. “FSH Receptor Gene p. Thr307Ala and p. Asn680Ser Polymorphisms Are Associated with the Risk of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 34, no. 8, Aug. 2017, pp. 1087–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-0953-z.

Konieczna, Aleksandra, et al. “Serum Bisphenol A Concentrations Correlate with Serum Testosterone Levels in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.), vol. 82, Dec. 2018, pp. 32–37. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2018.09.006.

Laganà, Antonio Simone, et al. “Metabolism and Ovarian Function in PCOS Women: A Therapeutic Approach with Inositols.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2016, 2016, p. 6306410. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6306410.

Lerchbaum, E., et al. “Susceptibility Loci for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome on Chromosome 2p16.3, 2p21, and 9q33.3 in a Cohort of Caucasian Women.” Hormone and Metabolic Research = Hormon- Und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones Et Metabolisme, vol. 43, no. 11, Oct. 2011, pp. 743–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1286279.

Li, Chao, et al. “Association of Rs10830963 and Rs10830962 SNPs in the Melatonin Receptor (MTNR1B) Gene among Han Chinese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Molecular Human Reproduction, vol. 17, no. 3, Mar. 2011, pp. 193–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gaq087.

Li, Meng-Fei, et al. “The Effect of Berberine on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients with Insulin Resistance (PCOS-IR): A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : ECAM, vol. 2018, Nov. 2018, p. 2532935. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2532935.

Li, Shang, et al. “Altered Circadian Clock as a Novel Therapeutic Target for Constant Darkness-Induced Insulin Resistance and Hyperandrogenism of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Translational Research, vol. 219, May 2020, pp. 13–29. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2020.02.003.

Liu, Zhengling, et al. “Effects of ADIPOQ Polymorphisms on PCOS Risk: A Meta-Analysis.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E, vol. 16, Dec. 2018, p. 120. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-018-0439-6.

Mahesh, Virendra B. “Hirsutism, Virilism, Polycystic Ovarian Disease, and the Steroid-Gonadotropin-Feedback System: A Career Retrospective.” American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 302, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. E4–18. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00488.2011.

Pau, Cindy T., et al. “Phenotype and Tissue Expression as a Function of Genetic Risk in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2017, p. e0168870. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168870.

Perelman, Dalia, et al. “Substituting Poly- and Mono-Unsaturated Fat for Dietary Carbohydrate Reduces Hyperinsulinemia in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Gynecological Endocrinology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 33, no. 4, Apr. 2017, pp. 324–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2016.1259407.

“Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Support Groups Are Helpful.” PCOS Awareness Association, https://www.pcosaa.org/overview. Accessed 21 July 2022.

Qiu, S., et al. “Exercise Training Improved Insulin Sensitivity and Ovarian Morphology in Rats with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Hormone and Metabolic Research = Hormon- Und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones Et Metabolisme, vol. 41, no. 12, Dec. 2009, pp. 880–85. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1234119.

Ranjzad, Fariba, et al. “A Common Variant in the Adiponectin Gene and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Risk.” Molecular Biology Reports, vol. 39, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 2313–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-011-0981-1.

Romitti, Mirian, et al. “Association between PCOS and Autoimmune Thyroid Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Endocrine Connections, vol. 7, no. 11, Oct. 2018, pp. 1158–67. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-18-0309.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. “Revised 2003 Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria and Long-Term Health Risks Related to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), vol. 19, no. 1, Jan. 2004, pp. 41–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh098.

Samimi, Mansooreh, et al. “Oral Carnitine Supplementation Reduces Body Weight and Insulin Resistance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 84, no. 6, June 2016, pp. 851–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.13003.

Shahebrahimi, Karoon, et al. “Comparison Clinical and Metabolic Effects of Metformin and Pioglitazone in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 20, no. 6, Dec. 2016, pp. 805–09. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.192925.

Sohrevardi, Seyed Mojtaba, et al. “Evaluating the Effect of Insulin Sensitizers Metformin and Pioglitazone Alone and in Combination on Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An RCT.” International Journal of Reproductive Biomedicine, vol. 14, no. 12, Dec. 2016, pp. 743–54.

Spinedi, Eduardo, and Daniel P. Cardinali. “The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and the Metabolic Syndrome: A Possible Chronobiotic-Cytoprotective Adjuvant Therapy.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2018, July 2018, p. e1349868. www.hindawi.com, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1349868.

staff, familydoctor org editorial. “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – Symptoms.” Familydoctor.Org, https://familydoctor.org/condition/polycystic-ovary-syndrome/. Accessed 21 July 2022.

Tagliaferri, Valeria, et al. “Melatonin Treatment May Be Able to Restore Menstrual Cyclicity in Women With PCOS: A Pilot Study.” Reproductive Sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), vol. 25, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 269–75. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719117711262.

Vahedi, Mahjoob, et al. “Metabolic and Endocrine Effects of Bisphenol A Exposure in Market Seller Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, vol. 23, no. 23, Dec. 2016, pp. 23546–50. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7573-5.

Valkenburg, O., et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms of GnRH and Gonadotrophic Hormone Receptors Affect the Phenotype of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), vol. 24, no. 8, Aug. 2009, pp. 2014–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep113.

Wei, Wei, et al. “A Clinical Study on the Short-Term Effect of Berberine in Comparison to Metformin on the Metabolic Characteristics of Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 166, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 99–105. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-11-0616.

Wickenheisser, Jessica K., et al. “Retinoids and Retinol Differentially Regulate Steroid Biosynthesis in Ovarian Theca Cells Isolated from Normal Cycling Women and Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 90, no. 8, Aug. 2005, pp. 4858–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-0330.

Wu, Chuyan, et al. “Exercise Activates the PI3K-AKT Signal Pathway by Decreasing the Expression of 5α-Reductase Type 1 in PCOS Rats.” Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 1, May 2018, p. 7982. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26210-0.

Wu, Yuanyuan, et al. “Metformin and Pioglitazone Combination Therapy Ameliorate Polycystic Ovary Syndrome through AMPK/PI3K/JNK Pathway.” Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, vol. 15, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 2120–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.5650.

Zou, Ju, et al. “Association of Luteinizing Hormone/Choriogonadotropin Receptor Gene Polymorphisms with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Risk: A Meta-Analysis.” Gynecological Endocrinology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 35, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 81–85. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2018.1498834.

Updated May 15, 2020