Key takeaways:

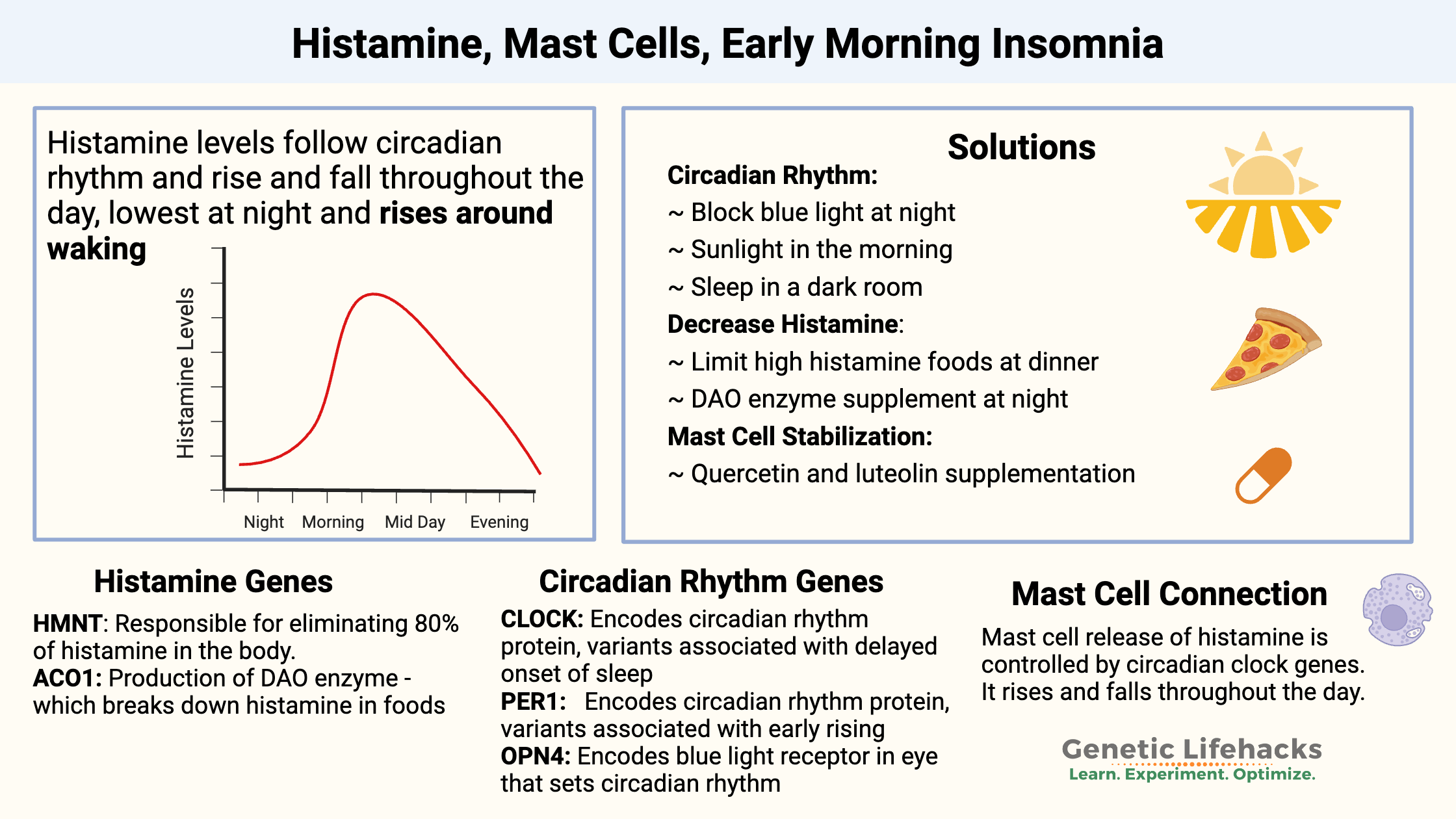

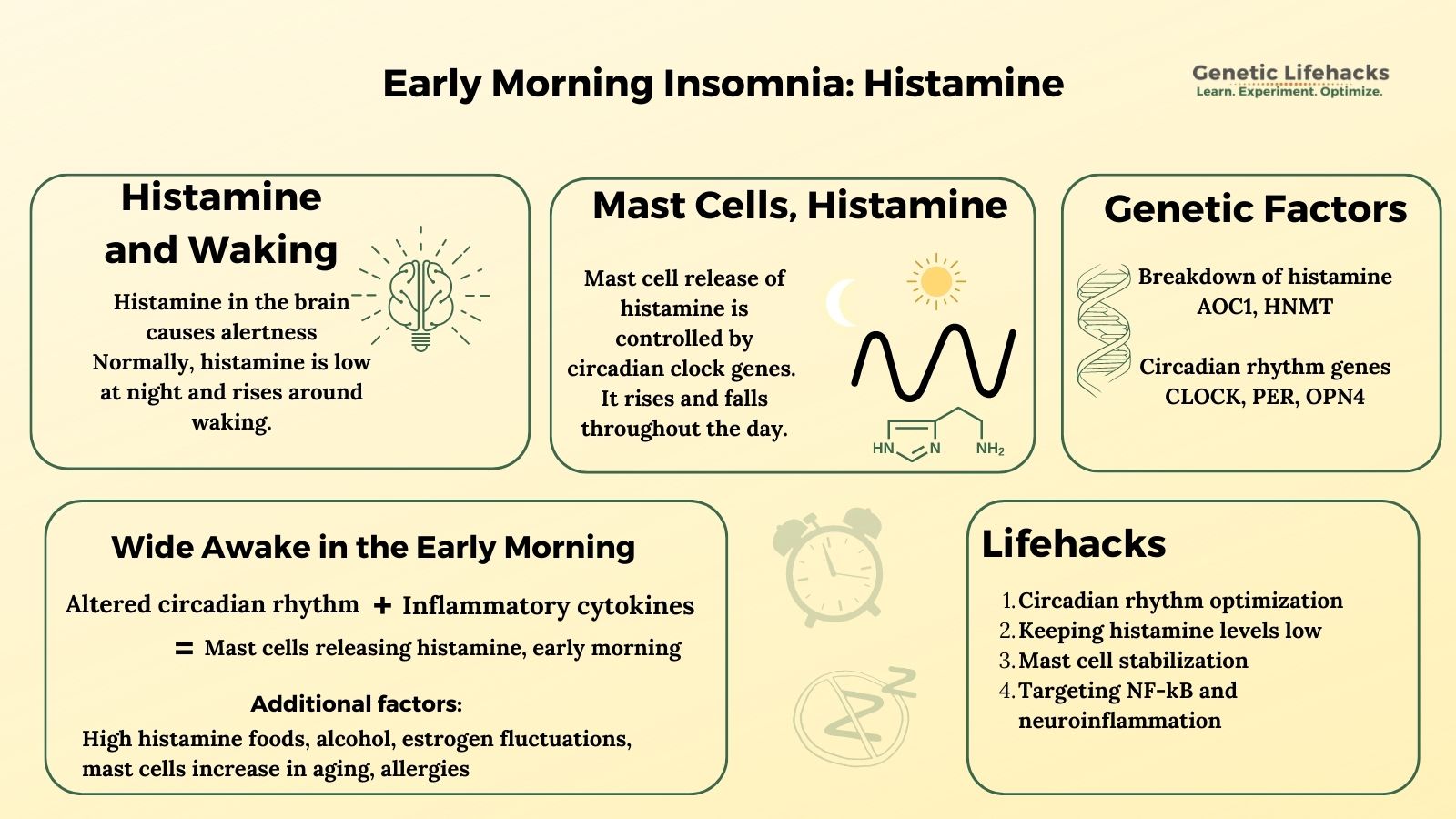

~ Histamine levels rise and fall throughout the day according to the circadian rhythm of mast cells.

~ In the brain, histamine acts as a neurotransmitter and is associated with wakefulness.

~ Neuroinflammation plus altered circadian rhythm of histamine release may be a cause of early morning insomnia (sometimes called histamine dumping).

~ Genetic variants in circadian rhythm genes may affect your response to environmental factors, such as light at night, that alter your circadian rhythm.

~ Genetic variants that decrease your histamine-degrading enzymes can increase your histamine levels.

Histamine and waking up at 3 AM: Histamine dumping?

Do you wake up at 3 or 4 in the morning, unable to go back to sleep? High histamine levels in the brain, sometimes called a ‘histamine dump’, could be the cause.

This article explains how histamine, mast cells, circadian rhythm, melatonin, and neuroinflammation intertwine to cause early morning insomnia – the dreaded 4 a.m. wake-up – for some people. We will start with histamine and circadian rhythm genes, and then move on to melatonin, mast cells, and neuroinflammation. Next, I’ll cover genes related to histamine metabolism and circadian rhythm. Finally, the Lifehacks section will tie it all together with solutions that are backed by research studies.

Members see their genotype report below, plus they can view solutions in the Lifehacks section. Not a member? Consider joining today.

Histamine: Rising and falling over the course of a day

Our hormones, neurotransmitters, and other cellular processes rise and fall throughout the day. This 24-hour rhythm is called the circadian rhythm, and it controls many things that happen in your body. For example, cortisol rises and falls in a daily rhythm, as does blood pressure.

Histamine levels also rise and fall in a circadian rhythm, rising in the early morning hours.[ref]

Histamine plays many roles in the body (more than just allergy symptoms!). It is produced at specific levels in different tissues throughout the day. Histamine binds to four different types of histamine receptors, causing different things to happen. For example, histamine released from cells lining the stomach activates H2 (histamine 2) receptors, which cause stomach acid to be produced. Over-the-counter H2 blockers, such as Pepcid and Tagamet, are able to stop the release of stomach acid.

One role of histamine is to act as a neurotransmitter in the brain. Histamine levels naturally rise in the morning hours and help us to feel more alert. Blocking the histamine receptors in the brain with diphenhydramine (Benadryl) causes drowsiness.[ref]

Sleeping, waking, and histamine:

Sleep vs. wakefulness:

The neurotransmitters and hormones that promote sleepiness include melatonin, serotonin, adenosine, and GABA. On the wakefulness side, we have histamine, cortisol, and orexin.[ref] (Problems with orexin production are a cause of narcolepsy.)

Why do we feel sleepy?

One factor in feeling sleepy every night is the buildup of adenosine in the brain. ATP, adenosine triphosphate, is used for energy in the brain throughout the day. As the molecule is broken apart for the energy in its bonds, the level of adenosine in the brain increases over the course of the day. This increase in adenosine then drives the activation of certain GABAergic neurons to promote sleep.

Another driver of sleep is melatonin levels rising and your circadian rhythm telling you that it is time to sleep.

Why do we wake up?

During normal sleep, the brain’s arousal systems are inhibited. At the end of the normal sleep period (~7.5 to 8 hours after falling asleep), the activation of the arousal centers in the brain causes someone to wake up.[ref]

Cortisol is one part of the activation of the arousal centers in the brain, and cortisol levels rise in the morning around the time that you wake up. This is called the cortisol awakening response.[ref]

Histamine-activated neurons are also located in the region of the brain that activates arousal. Animal studies show us that the histaminergic neurons are activated during wakefulness. Blocking these neurons — or the loss of histamine production in the neurons — causes sleepiness.[ref] Histamine also interacts with sleep cycles. When researchers block histaminergic neurons in animals, it causes sleep-wake cycle fragmentation and increased delta power in non-REM sleep.[ref]

Mast cells release histamine:

Most people are familiar with histamine from its role in allergic reactions — causing a runny nose, itching, hives, etc. Mast cells are the innate immune system cells that release histamine in large quantities when stimulated by a pathogen, allergen, or inflammatory cytokines.

However, mast cells can sometimes degranulate too easily, releasing histamine and other molecules when they normally wouldn’t. (Read more about mast cell activation syndrome)

Recent research shows that mast cells release a baseline level of histamine throughout the day. This release is controlled by core circadian rhythm genes. More on this in a minute.

Let me explain why this is important for early morning waking…

Circadian rhythm of histamine release:

Circadian rhythm refers to the built-in 24-hour molecular clock that controls about 40% of the processes in our bodies.

Our circadian rhythm is more than just the sleep/wake cycle, although sleep is part of it. For example, your intestinal cells don’t need to produce digestive enzymes in the middle of the night. Those enzymes are produced at times when you normally eat food during the day.

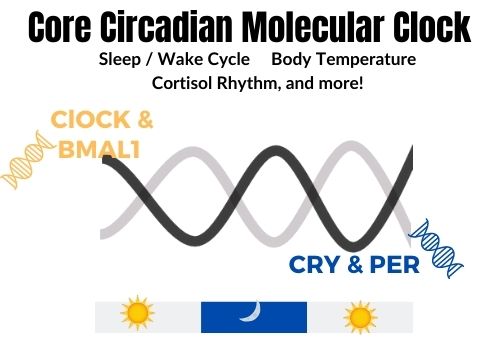

Our built-in circadian rhythm is controlled by a molecular clock driven by the rising and falling expression of core circadian clock genes. During the day, CLOCK and BMAL1 genes are expressed, and during the night, PER and CRY levels rise. It is this rise and fall – a molecular clock – that controls the circadian rhythm of genes and systems throughout the body.[ref]

Part of what drives circadian rhythm is the rise and fall of melatonin levels. At night, melatonin is released from the pineal gland in the brain. The ‘shut off’ switch for melatonin production is light in the blue wavelengths hitting specific receptors in your eye. This is why blue light, such as from your phone, TV, or overhead lights, is detrimental at night. The blue wavelength light slows the normal nighttime production of melatonin, which then feeds back to affect circadian clock gene expression. [ref]

Histamine is produced by the body at a basal level throughout the day and night. The level of histamine rises and falls over the course of the 24-hour day, with a peak in production during the morning hours just before waking, along with peaks around 1 p.m. and 7 p.m. The average time of the morning histamine peak is around 5:30 a.m.[ref] In people with asthma, early morning histamine release corresponds to increased early morning asthma attacks.[ref]

Animal studies show that normal blood histamine levels are controlled by mast cell production of histamine. In mast-cell-deficient mice, baseline histamine levels are decreased by ~70%. These animal studies also show that the circadian rhythm of histamine is controlled by mast cells. Gene knockout studies show that histamine release by mast cells is controlled by the circadian clock genes.[ref] Animals with mutations in core circadian clock genes show that the circadian rhythm of mast cells is important in how much of a reaction they have to an allergen.[ref]

What about mast cells and circadian rhythm in people?

In people with allergies or asthma, researchers have found that mast cell activation is exacerbated at certain times of the day due to the circadian rhythm of the mast cells.[ref]

Early morning insomnia: circadian rhythm and mast cell degranulation

Enough background science…let’s put it all together to explain why early morning histamine dumping causes insomnia.

Researchers believe that the excessive release of histamine from mast cells in the early morning hours is due to a disrupted circadian rhythm. Associated with the circadian disruption is the activation of mast cells by inflammatory cytokines.[ref]

So it is a two-hit scenario: circadian rhythm disruption in mast cells along with elevated inflammatory cytokines.

I’ll cover ways of addressing both in the Lifehacks section. But first, let’s go through how histamine levels are normally regulated to explain how what you eat may also play a role in early morning insomnia.

Breaking down histamine:

Histamine can be made by cells, released by mast cells, or ingested by eating foods high in histamine. Levels are regulated by systems that break down or degrade histamine.

In the body, there are two ways to break down histamine:

- DAO enzyme (AOC1 gene) breaks down histamine from food in the intestines.

- Histamine n-methyltransferase enzyme (HNMT gene) metabolizes histamine in cells throughout the body.

Genetic variants in these two genes can affect how well you break down and get rid of histamine.

See your genes for histamine breakdown in the Genotype report below.

Related article: Histamine Intolerance Genes

Circadian rhythm genes:

Core circadian rhythm genes include:

- CLOCK and BMAL1 (the positive arm of the circadian clock)

- PER and CRY (the negative arm of the circadian clock)

The molecular circadian clock is located in the hypothalamus region of the brain in an area known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus. During the day, levels of the CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins rise, triggering cellular events that need to occur during the day. Then at night, the levels of the CRY1/2 and PER1/2/3 proteins rise, signaling for nighttime processes to take place.

Here’s a quick visual for you showing the Circadian Clock Genes:

Which of these genes are important for histamine?

Research in animals shows that the CLOCK gene rhythm in mast cells is important for baseline histamine release as well as allergic reactions.[ref]

The PER2 gene also impacts allergic reactions and mast cell activation.[ref]

See your CLOCK, PER, and melatonin genes in the genotype report below.

Tying this all together: Key to histamine-related early morning waking

Higher histamine in the morning just before you wake up is natural, but what causes it to exceed your histamine limit in the early morning hours?

Neuroinflammation:

I mentioned above that mast cells release lots of histamine when activated by pathogens and allergens. However, mast cells also release histamine in the presence of certain inflammatory cytokines and immune system cells.

NF-kB (nuclear factor-kB) is a transcription factor that regulates many immune and inflammatory response genes.[ref] It can turn up the heat at times when inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-13, and TNF-alpha, are needed.[ref]

NF-kB also regulates melatonin production in the pineal gland and in cells that produce melatonin. All of this points towards NF-kB as a key element in preventing the mast cell activation and histamine release. One paper explains: “The circadian-mediated behaviors of melatonin and histamine in MCs are involved in different pathways with various factors including NF-κB which stands out as the common key player. “[ref]

Low melatonin:

Mast cells have melatonin receptors on their surface. When melatonin binds to the mast cells, it decreases the activation and degranulation.[ref][ref]

Decreased melatonin production due to exposure to light from electronics could play a role in the activation of mast cells to release histamine at the wrong time. More details on this can be found in the Lifehacks section.

The research clearly points to inflammation as a key player interacting with altered circadian rhythms. Low melatonin probably plays a role in increased mast cell activation.

Intermittent hypoxia in sleep apnea:

Animal studies show that sleep apnea, which causes intermittent hypoxic episodes, causes both higher histamine levels in the brain during sleep and also decreases sleep quality. Importantly, blocking the histamine receptor with an antihistamine (H1 receptor antagonist) improved sleep quality and decreased fragmentation.[ref]

I wanted to touch on a couple of other factors that can increase histamine levels and may interact with early morning wakefulness. To be clear, research shows that these factors affect histamine, but I don’t have direct research linking them to early morning insomnia.

4 Additional factors that could increase histamine release:

Estrogen:

Mast cells have estrogen receptors on their cell surface. This may make them more easily triggered when estrogen levels are high or when estrogen levels fluctuate (menstrual changes or perimenopause).

Related article: Estrogen, mast cells, and histamine

Allergies:

Seasonal allergies can increase overall histamine levels. In addition, environmental allergies, such as reactions to a down pillow, dust mites, or mold in your bedroom, could trigger histamine release at night. If you are prone to allergies, check your bedroom for allergens.

Allergy symptoms are usually reduced at night due to circadian suppression of mast cell activation.[ref] However, allergens combined with disruption of circadian rhythm could alter histamine levels at night.

Mast cells increase with age:

A recent animal study shows that mast cells increase in the gut and brain with aging.[ref] This may mean that mast cell stabilization is more important as we age.

Alcohol:

The DAO enzyme, which breaks down histamine, is inhibited by alcohol.[ref] Alcohol can also disrupt sleep in other ways

Related article: Alcohol and histamine intolerance

Recap: Pulling this all together

This is getting complicated. Here’s a table that pulls together the causes listed above with the genes listed below in the genotype section.

| Factor | Explanation | Genetic/ Environmental Link | Key Genes/Involved Elements | Potential Solutions/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine circadian rhythm | Histamine peaks early morning; follows a 24h rhythm | Controlled by circadian genes, mast cell clock | CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY, Mast cells | Optimize circadian rhythm (light/dark cycles, routines) |

| Mast cell activation/neuroinflammation | Disrupted circadian rhythm & inflammation → excessive histamine release | Inflammatory cytokines, clock gene disruption | NF-kB, IL-6, IL-13, TNF-alpha, Mast cells | Control inflammation, stabilize mast cells, support melatonin |

| Histamine breakdown, DAO enzyme deficiency | Reduced DAO/HNMT function → increased histamine | AOC1/HNMT gene variants | AOC1 (DAO), HNMT | DAO supplements, low-histamine diet |

| Environmental triggers | Allergens, alcohol, food, blue light, aging, chemicals | Interacts with genetic vulnerability | COMT, OPN4 | Reduce exposures, allergy management, block blue light |

| Diet contributors | Fermented, aged, and other high-histamine foods, histamine-liberating foods | Diamine oxidase function (AOC1 gene) | AOC1 (DAO) | Low-histamine diet, DAO supplement |

| Supplements (mast cell/NF-kB focus) | Mast cell stabilizers/NF-kB inhibitors (quercetin, luteolin, resveratrol, berberine, etc.) | Check interactions with COMT genotype | COMT | Personalize by genotype, experiment with supplements |

Genotype report:

This genotype report is divided into two sections:

- Genetic variants that have solid research on their impact on histamine levels. Please read the histamine intolerance article for the full list of possible associated genes.

- Genetic variants that impact the core circadian clock.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks: Sleeping peacefully past 4 a.m.

If you have genetic variants related to histamine intolerance or simply resonate with the information on circadian rhythm and early morning histamine dumping, then let’s take a look at a bunch of possible solutions. You can pick and choose what you think will work best for you.

However, histamine isn’t the only cause of early morning insomnia. If you’ve gotten this far and don’t think histamine is the problem for you, read about early morning insomnia and tryptophan.

4-step plan to stay asleep:

- Keep circadian rhythm on track

- Reducing histamine levels through diet

- Stabilizing mast cells with natural supplements

- Targeting NF-kB and neuroinflammation with natural supplements

Here is a summary table of lifehacks and recommendations for managing histamine-related early morning insomnia that we will cover in depth below:

| Lifehack | Category | Mechanism | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistent light-dark schedule, avoid bright lights after sunset | Sleep Hygiene | Strengthens circadian rhythm, regulates histamine release | Blue light blocking glasses, dim lights at night, morning sunlight |

| Reduce allergens in sleeping area (dust, mold, pets) | Environment | Limits mast cell activation and nighttime histamine release | HEPA filter, frequent bedding washes, pet-free bedroom |

| Avoid high-histamine foods in evening | Diet | Prevents histamine spikes that affect sleep onset/maintenance | Skip fermented, aged, processed foods after 4pm |

| Try DAO enzyme supplements before high-histamine meals | Supplement | Supports histamine degradation in gut | Take just before meals, individual response may vary |

| Consider mast cell stabilizing supplements (quercetin, luteolin) | Supplement | Reduces mast cell degranulation and histamine release | Take consistently, may interact with COMT genotype |

| Limit alcohol and NSAIDs in the evening | Lifestyle | Both impair histamine breakdown enzymes (DAO, HNMT) | Avoid after 4pm, especially if sensitive to histamine |

| Support melatonin (darkness, possible low-dose supplement) | Sleep Hygiene | Melatonin counters histamine in the brain, helps signal sleep | Dark room, consider 0.3-1mg melatonin if needed |

| Optimize bedroom temperature (cool, not cold) | Sleep Hygeine | Overheating triggers histamine/awakening | Aim for 65-68°F (18-20°C), light bedding |

I’ll cover each of these below in depth.

While all of these lifestyle and supplement changes have research behind them for the individual topic, I haven’t found clinical trials or research studies that show that this will work for everyone with histamine-induced early waking. Take this as a more personal narrative of what works for me, along with why I think it works.

Step 1) Optimize Circadian Rhythm:

In a nutshell: Have an orderly daily rhythm to life.

It’s easy to see that animals and kids have a rhythm that is innate. Mice are active at night and roosters crow in the morning… Anyone who has raised kids knows that nap time is sacred.

In our modern world, we have lost track of our natural daily rhythm. Light in the blue wavelengths at night is a recent invention — even the old incandescent light bulbs gave off little blue light. Eating at odd hours and staying up late watching television disrupt our circadian rhythm.

To keep circadian rhythm on track:

- Sleep in the dark. Get blackout curtains to block street lights, and cover up any of the glowing indicator lights in your bedroom. Alternatively, get a good sleep mask.[ref]

- Block artificial light for two hours before bedtime. You can use 100% blue blocking glasses, or just turn your overhead lights down and use lamps with orange or yellow bulbs. A study involving adults looking at an iPad for a couple of hours before bed found that using 100% blue light blocking glasses increased melatonin secretion and improved sleep.[ref]

- Go outside in the sunlight when you get up in the morning. This shuts down melatonin production for the day, increases melatonin production for the next night, and improves sleep quality.[ref]

- Brighter lights during the day when working inside can increase melatonin at night.[ref]

- Eat on a regular schedule. Your circadian rhythm is also set by when you eat. Try to eat only during the daylight hours and stop eating three hours before bed.

Optimal Sleep Timing:

Studies in Amish communities show that without electric lights, TVs, and modern electronics, people tended to go to sleep around 9 or 9:30 and get up around 5:30. However, there were individual outliers. Some went to sleep earlier, getting up before sunrise, and others went to bed a little later. [ref]

Your optimal sleep timing without the influence of artificial light is likely determined in part by your genetic variants in the circadian genes. For example, people with two copies of the CLOCK variant (above in the genotype report) averaged a ~45-minute later sleep onset.[ref] Most people need 7.5 to 8 hours of sleep a night, but there are some people who need more or a little less. All of this variation in sleep timing and length was an advantage in villages and communities. In times past, having someone awake late to raise the alarm kept the village safe from attacks or animals. Similarly, it was an advantage to have some of the population awake before sunrise.

For most people today, the optimal time to sleep is determined by when you have to get up for work. Do the math and plan to fall asleep 7.5 to 8 hours before your alarm clock goes off.

Get more full-spectrum light during the day:

Exposure to full-spectrum light in the morning increases melatonin production at night.[ref] Modern life keeps us indoors more than in the past. Another study of the Amish community found that their exposure to light during the day was up to 8 times higher than that of people living in urban areas.[ref]

What if you work in an office or store? Adding bright, full-spectrum lighting to your work environment is one option. Another is to plan to eat lunch or dinner outside, take a walk, or have your morning cup of coffee on your patio.

Supplemental melatonin:

Melatonin is important in setting circadian rhythm, and melatonin levels decrease with aging as the pineal gland calcifies.

If you decide to supplement with melatonin, I would encourage you to consider a timed-release formula that better mimics natural melatonin release. Additionally, a lot of melatonin supplements contain larger doses than what is naturally produced at night, so you may want to consider a low-dose, timed-release formula to mimic natural melatonin production.

Related article: Supplemental Melatonin

Weekends and social jetlag:

For many of us, the weekend is the time when sleep in and stay up late, throwing our circadian rhythm off track. Researchers call the change in sleep/wake timing ‘social jetlag’ when people go to bed two or three hours later on the weekend. It’s easy to think that going to bed late and sleeping in on Saturday and Sunday is normal, but it really does throw your circadian rhythm off track for a few days. You adjust to the weekday rhythm by Wednesday, only to be thrown off schedule again by Friday.

Experiment and see how you feel:

I would challenge you to try going to bed (and eating) at the same time for a few weeks. Sleep in the dark and go outside in the morning. Get your circadian rhythm on track, and then pay attention to how you feel when you vary your schedule.

Step 2) Lowering histamine levels by diet and supplements

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Graphical Abstract:

Related articles:

Histamine Intolerance: Genetic Report, Supplements, and Real Solutions

MRGPRX2: Mast Cells, Itching, & Drug Hypersensitivity Reactions, Including Fluoroquinolones