Key takeaways:

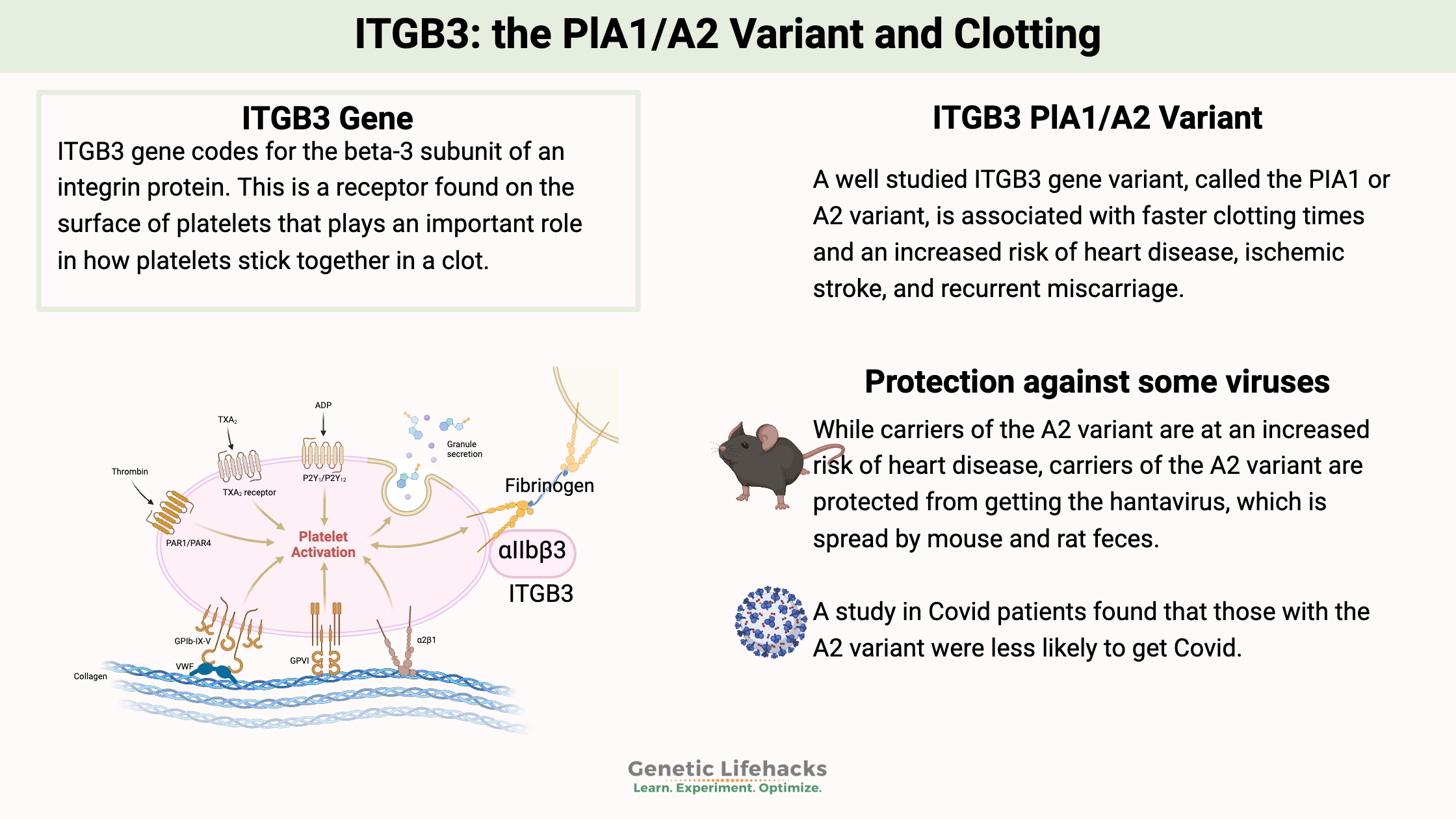

~ The ITGB3 gene encodes a protein receptor on the surface of platelets.

~ A variant in the gene, called PlA1 or PlA2, is associated with increased clotting.

~ The ITGB3 PlA2 variant is also associated with susceptibility to certain viruses. The variant protects against Hantavirus infection and alters the risk of Covid.

The ITGB3 Gene and the PlA1/A2 Variant

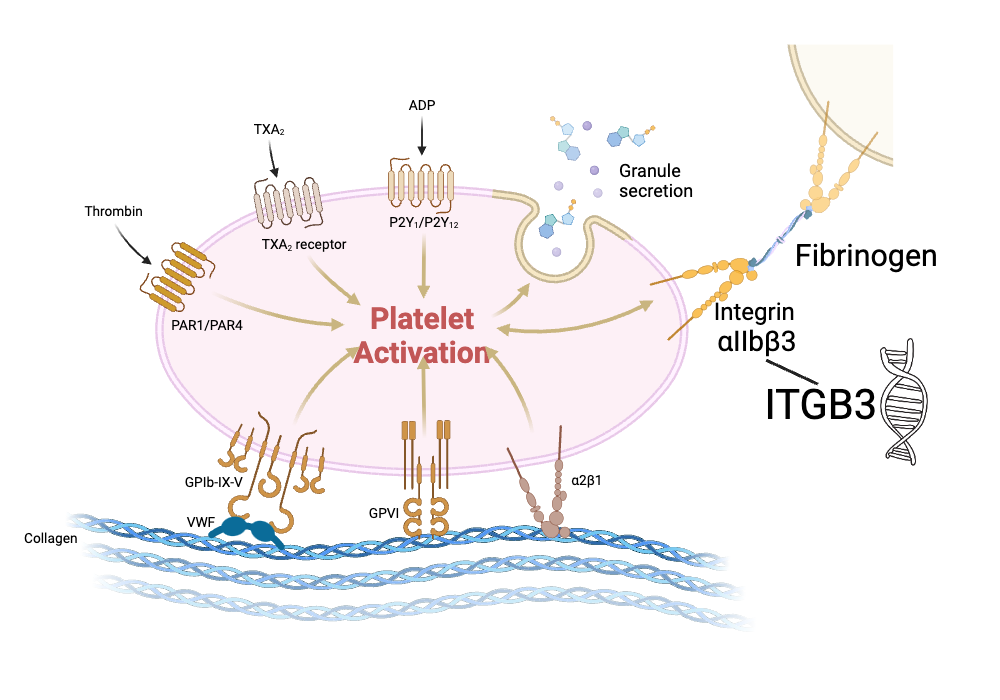

ITGB3 gene codes for the beta-3 subunit of an integrin protein. This is a receptor found on the surface of platelets that plays an important role in how platelets stick together in a clot. The integration protein (integrin alpha IIb/beta3) binds to fibrinogen when activated to help platelets clump together into a clot.

The ITGB3 gene is also referred to as GPIIIa or glycoprotein IIIa in older studies. A common variant in the gene was identified decades ago, and the two alleles were named PlA1 and PlA2 (or PIA1/A2). In addition, the ITGB3 protein is involved in cell-to-cell adhesion as well as the migration of cancer cells.

(Not to be confused with the PAI1 gene – platelet activation inhibitor-1 gene, which is also involved in clotting.)

Clotting cascade: Role of ITGB3

The clotting action is vitally important when you cut yourself — but clotting too much or too quickly can also be a problem. Blood clots can cause heart attacks and strokes. Additionally, blood clots that form in the large veins of the leg or arm can cause deep vein thrombosis.

This is where the two different variants, PlA1 and PlA2, come into play, with the PlA2 variant increasing clot risk due to increased platelet aggregation.

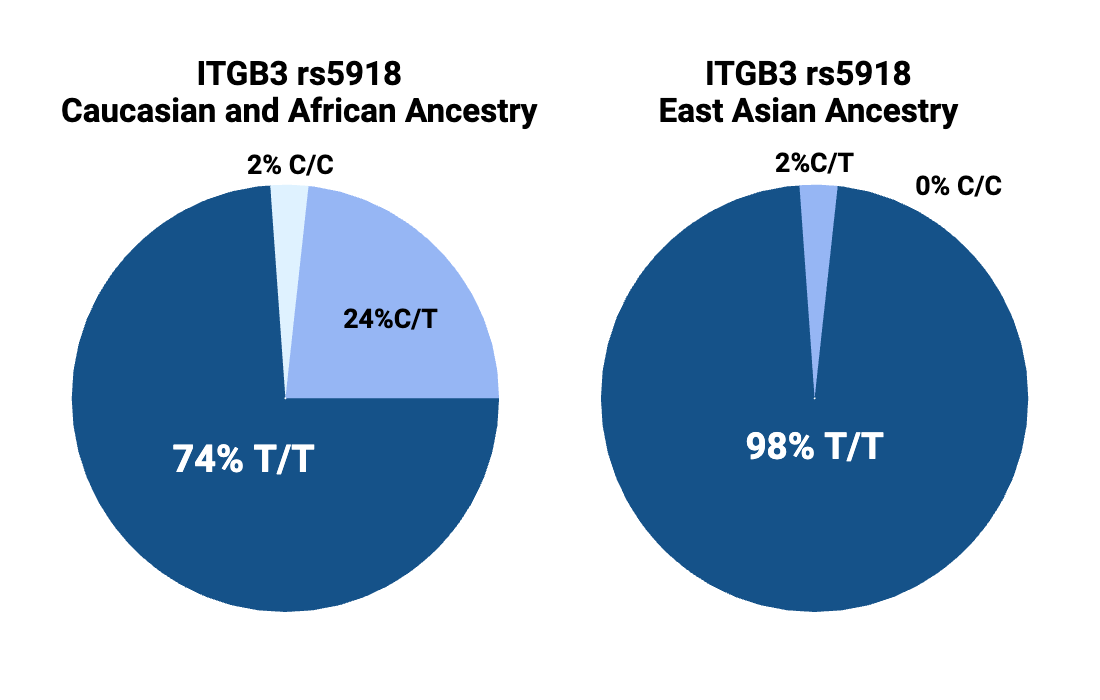

The PlA2 variant (CC or CT genotype below) is found in about 25% of people with Caucasian or African ancestry, but it is only found in 1-2% of people with Chinese or Japanese ancestry.

The ITGB3 PlA1/A2 variant and increased cardiovascular risk:

Hundreds of studies have been done on the ITGB3 genetic variant known as PlA1/A2. Here is an overview of some of the findings:

- A study of men aged 20-25 found that those carrying the A2 variant had faster blood clotting times.[ref]

- A study of men who died of sudden cardiac death found that the A2 variant more than doubled the relative risk of sudden cardiac death under the age of 50.[ref]

- The results of one study that included both men and women found only women who carried the A2 variant were at a higher risk of deep venous thrombosis.[ref]

- An overall meta-analysis combining the data from 14 studies concluded a statistical increase in the risk of heart attacks exists, with the increase in relative risk being higher in younger people (absolute risk still low).[ref]

- Researchers looked at 1,202 Caucasian patients in an atherosclerosis study and found the A2 variant carriers may be predisposed to an “increased risk of atherosclerotic plaque rupture.”[ref]

- A study of Pakistani patients found the variant has no impact on aspirin resistance.[ref]

Recurrent Miscarriages:

Increased clotting can be a problem in pregnancy and increases the relative risk of miscarriages.

- Women carrying the variant may be at an increased risk of having recurrent miscarriages.[ref]

- Another study in women who had miscarried previously showed that the PlA2 allele was associated with increased platelet reactivity.[ref]

Platelets and the Immune Response:

Your circulating platelets also play an important role in detecting and binding to viruses. Different types of viruses can interact with surface receptors on platelets, and platelet activation plays a role in the body’s response to viruses.

Some viruses bind to receptors found on the surfaces of platelets (as well as other cells), and some viruses, such as adenoviruses, use cell surface receptors for viral entry. The integrin proteins, especially β3 integrins (ITGB3), are important in binding to viruses and for cell entry.[ref][ref][ref]

Protection from the hantavirus:

Most genetic variants that have a downside also have a positive one: There usually is a reason the variant survives in the population. Tradeoffs. The downside of the A2 variant is obvious – increased relative risk of early heart attack deaths, especially before the time of modern medical care. Since carrying this ITGB3 gene variant increased early heart attack deaths, at some point, the variant should have dwindled out in the human genome. Balancing out this negative is a positive reason the variant still is found in the population. Research shows the variant offers protection from dying from pathogens that cause excessive bleeding.

Carriers of the A2 variant are protected from getting sick from the hantavirus. The spreading of hantavirus occurs from mouse and rat feces. There are multiple strains of hantavirus, including an Andes virus strain and hantavirus strains found in the southwest and mountainous regions of the US.

The hantavirus causes cardiopulmonary responses due to increased vascular permeability and decreased platelet clotting.[ref] Studies show people carrying the A2 variant are less likely to get the hantavirus. In one study, none of the hantavirus patients carried two copies of the PlA2 variant. In the group exposed to the virus but who didn’t get sick, 11% of them carried two copies of the variant.[ref]

Covid Susceptibility and Severity: ITGB3 PlA1/A2 variants

Another study looked at genetic variants that increased or decreased the risk of getting Covid. The results showed that the ITGB3 A2 variant reduced the relative risk of getting Covid.[ref]

However, in people with the A2 variant who do catch Covid, it may be more severe. A study found they were more likely to have more severe Covid. In the original strain of the virus, severe Covid was associated with increased prothrombotic and cardiovascular complications. The study results showed that the A2 allele was associated with an increased relative risk of severe Covid.[ref]

PIA1/A2 Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

If you carry the A2 variant, take this as a ‘heads up’…know the signs of a blood clot and be proactive about your heart health.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

References:

Floyd, Christopher N., et al. “The PlA1/A2 Polymorphism of Glycoprotein IIIa as a Risk Factor for Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-Analysis.” PLOS ONE, vol. 9, no. 7, July 2014, p. e101518. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101518.

Ivanov, Petar D., et al. “Polymorphism A1/A2 in the Cell Surface Integrin Subunit Β3 and Disturbance of Implantation and Placentation in Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 94, no. 7, Dec. 2010, pp. 2843–45. www.fertstert.org, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.015.

Khatami, Mehri, et al. “Common Rs5918 (PlA1/A2) Polymorphism in the ITGB3 Gene and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease.” Archives of Medical Sciences. Atherosclerotic Diseases, vol. 1, no. 1, Apr. 2016, pp. e9–15. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5114/amsad.2016.59587.

—. “Common Rs5918 (PlA1/A2) Polymorphism in the ITGB3 Gene and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease.” Archives of Medical Sciences. Atherosclerotic Diseases, vol. 1, no. 1, Apr. 2016, pp. e9–15. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5114/amsad.2016.59587.

Komsa-Penkova, Regina, et al. “Rs5918ITGB3 Polymorphism, Smoking, and BMI as Risk Factors for Early Onset and Recurrence of DVT in Young Women.” Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis: Official Journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis, vol. 23, no. 6, Sept. 2017, pp. 585–95. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/1076029615624778.

Kucharska-Newton, Anna M., et al. “Association of the Platelet GPIIb/IIIa Polymorphism with Atherosclerotic Plaque Morphology: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 216, no. 1, May 2011, pp. 151–56. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.038.

Martínez-Valdebenito, Constanza, et al. “A Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism of ΑVβ3 Integrin Is Associated with the Andes Virus Infection Susceptibility.” Viruses, vol. 11, no. 2, Feb. 2019, p. 169. www.mdpi.com, https://doi.org/10.3390/v11020169.

Mikkelsson, Jussi, et al. “Glycoprotein IIIa PlA1/A2 Polymorphism and Sudden Cardiac Death.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 36, no. 4, Oct. 2000, pp. 1317–23. jacc.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00871-8.

Mukarram, Osama, et al. “A Study into the Genetic Basis of Aspirin Resistance in Pakistani Patients with Coronary Artery Disease.” Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 29, no. 4, July 2016, pp. 1177–82.

Oliver, Kendra H., et al. “Pro32Pro33 Mutations in the Integrin Β3 PSI Domain Result in ΑIIbβ3 Priming and Enhanced Adhesion: Reversal of the Hypercoagulability Phenotype by the Src Inhibitor SKI-606.” Molecular Pharmacology, vol. 85, no. 6, June 2014, pp. 921–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.114.091736.

—. “Pro32Pro33 Mutations in the Integrin Β3 PSI Domain Result in ΑIIbβ3 Priming and Enhanced Adhesion: Reversal of the Hypercoagulability Phenotype by the Src Inhibitor SKI-606.” Molecular Pharmacology, vol. 85, no. 6, June 2014, pp. 921–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.114.091736.

Ridker, P. M., et al. “PIA1/A2 Polymorphism of Platelet Glycoprotein IIIa and Risks of Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, and Venous Thrombosis.” Lancet (London, England), vol. 349, no. 9049, Feb. 1997, pp. 385–88. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80010-4.

Szczeklik, Andrzej, et al. “Relationship between Bleeding Time, Aspirin and the PlA1/A2 Polymorphism of Platelet Glycoprotein IIIa.” British Journal of Haematology, vol. 110, no. 4, 2000, pp. 965–67. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02267.x.

Undas, A., et al. “Pl(A2) Polymorphism of Beta(3) Integrins Is Associated with Enhanced Thrombin Generation and Impaired Antithrombotic Action of Aspirin at the Site of Microvascular Injury.” Circulation, vol. 104, no. 22, Nov. 2001, pp. 2666–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/hc4701.099787.

—. “Pl(A2) Polymorphism of Beta(3) Integrins Is Associated with Enhanced Thrombin Generation and Impaired Antithrombotic Action of Aspirin at the Site of Microvascular Injury.” Circulation, vol. 104, no. 22, Nov. 2001, pp. 2666–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/hc4701.099787.