Key takeaways:

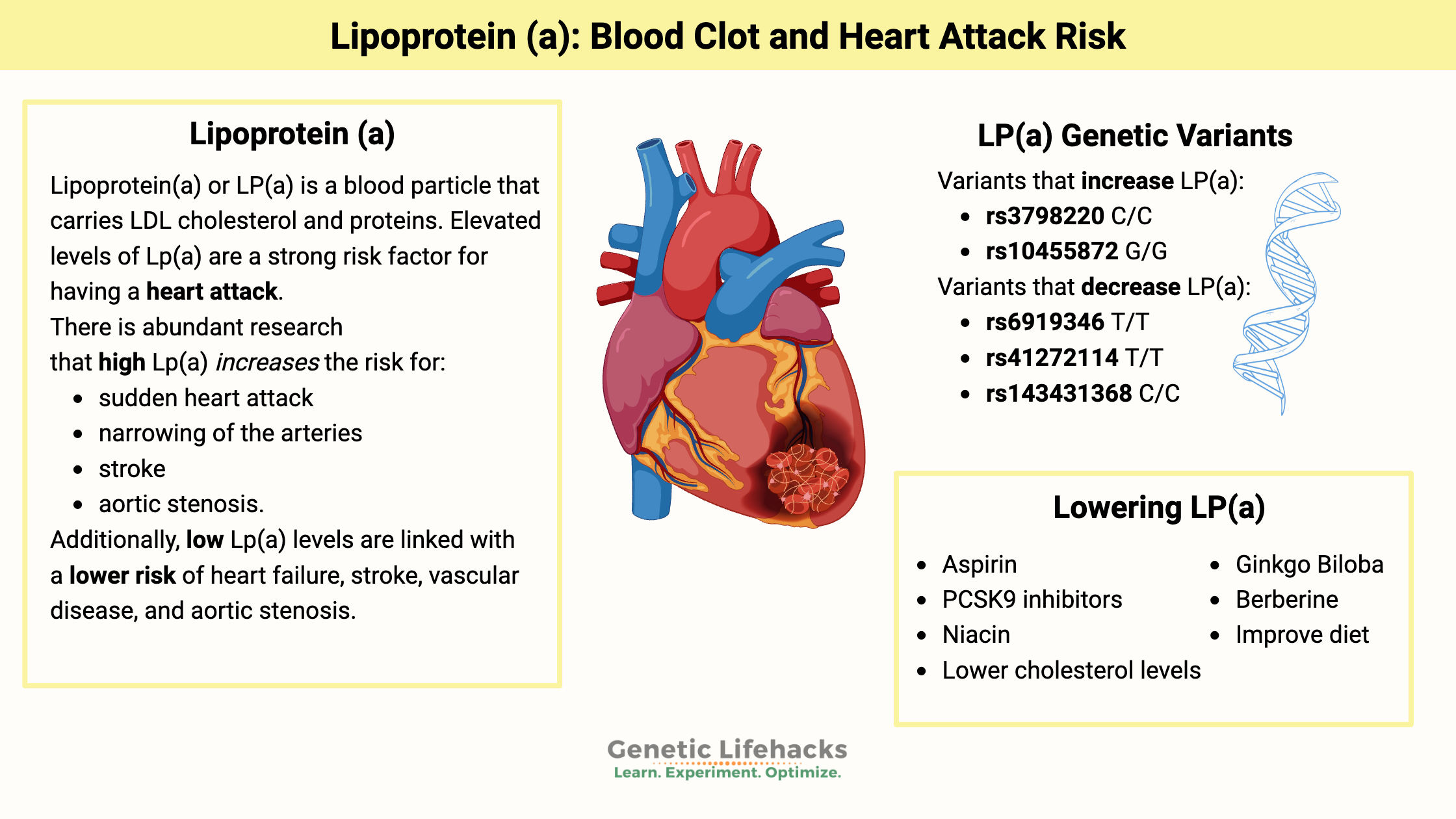

~ Lipoprotein(a) – Lp(a) – is a cholesterol carrier.

~ High Lp(a) levels are strongly linked to an increased risk of heart attacks and aortic stenosis.

~ Genetic variants in the LPA gene drive Lpa(a) levels.

~ Knowing that you are likely to have genetically higher Lp(a) can help you understand when it is important to test it and talk with a doctor.

This article digs into research on lipoprotein (a) and the genetic variants that can cause it to be elevated. I’ll explain how to check your genetic data (e.g., 23andMe or AncestryDNA) to see if you carry the variants and then the next steps to take with getting blood tests done. Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

What is lipoprotein(a)?

Lipoprotein(a) or LP(a) — “L P little a” — is a blood particle that carries LDL cholesterol and proteins. Elevated levels of Lp(a) are a strong risk factor for having a heart attack due to atherosclerosis.[ref]

We all know that fats and water don’t mix. It remains true in the body regarding moving around fats in the bloodstream. The term lipoprotein is a general term for a glob of fatty acid plus protein that is packaged so it can easily be transported throughout the body. Lipoproteins include low-density and high-density cholesterol.

Atherosclerosis:

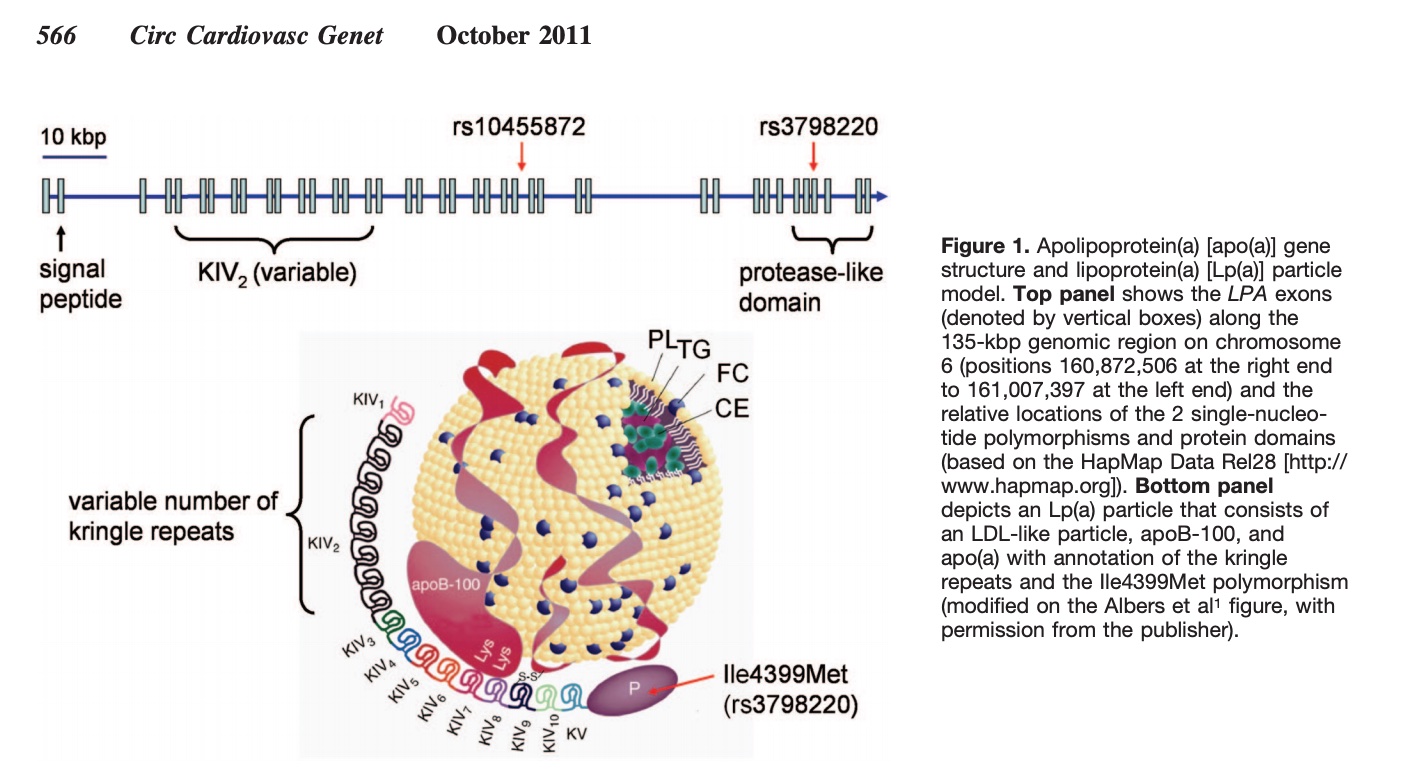

Lipoprotein (a) includes an LDL particle bound to an apolipoprotein (a) – known as apo(a) – and apoB100. The apo(a) part is what increases atherosclerosis. It also promotes clotting by interfering with the way that the body dissolves clots.[ref] So, you have a double-whammy of increasing atherosclerosis via increased inflammation plus oxidized LDL. The LDL tends to oxidize once inside a vessel wall adding more inflammation responses because their structure has changed. It all adds to a mechanism that increases the risk of blood clots and atherosclerotic plaque.[ref]

Prothrombic effect:

In addition to increasing atherosclerosis, higher Lp(a) levels also have a prothrombotic – clot-forming – effect during inflammation. Lp(a) can bind to fibrin and defensins that are released by neutrophils during infections or inflammation. [ref]

The Lp(a) molecule can vary a lot in size, and you can inherit two different sizes of Lp(a) – one from mom and one from dad. These different-sized Lp(a) molecules can increase or decrease your risk of heart attacks and strokes.[ref]

Lipoprotein(a) levels are hereditary:

“Family history” is always mentioned by the doctor as an important indicator of your risk of heart disease, especially if a family member had a heart attack at a young age. Lp(a) is often the reason that this question is asked.

A significant way that researchers have found family history plays a role in early heart attacks is by the genetic variants that increase lipoprotein(a).

Lp(a) levels are estimated to be 90% hereditary.[ref] (That’s really high when it comes to hereditary estimates!)

High Lp(a) increases the risk of cardiovascular events:

There is abundant research that high Lp(a) significantly increases the risk for:[ref][ref][ref][ref][ref]

- sudden heart attack

- narrowing of the arteries

- stroke

- aortic stenosis

- peripheral artery disease

- heart failure

For example, moderate to high levels of Lp(a) increase the risk of coronary stenosis (narrowing of the arteries) by 67%.[ref]

Additionally, the opposite is true –> low Lp(a) levels are linked with a lower risk of heart failure, stroke, vascular disease, and aortic stenosis.[ref]

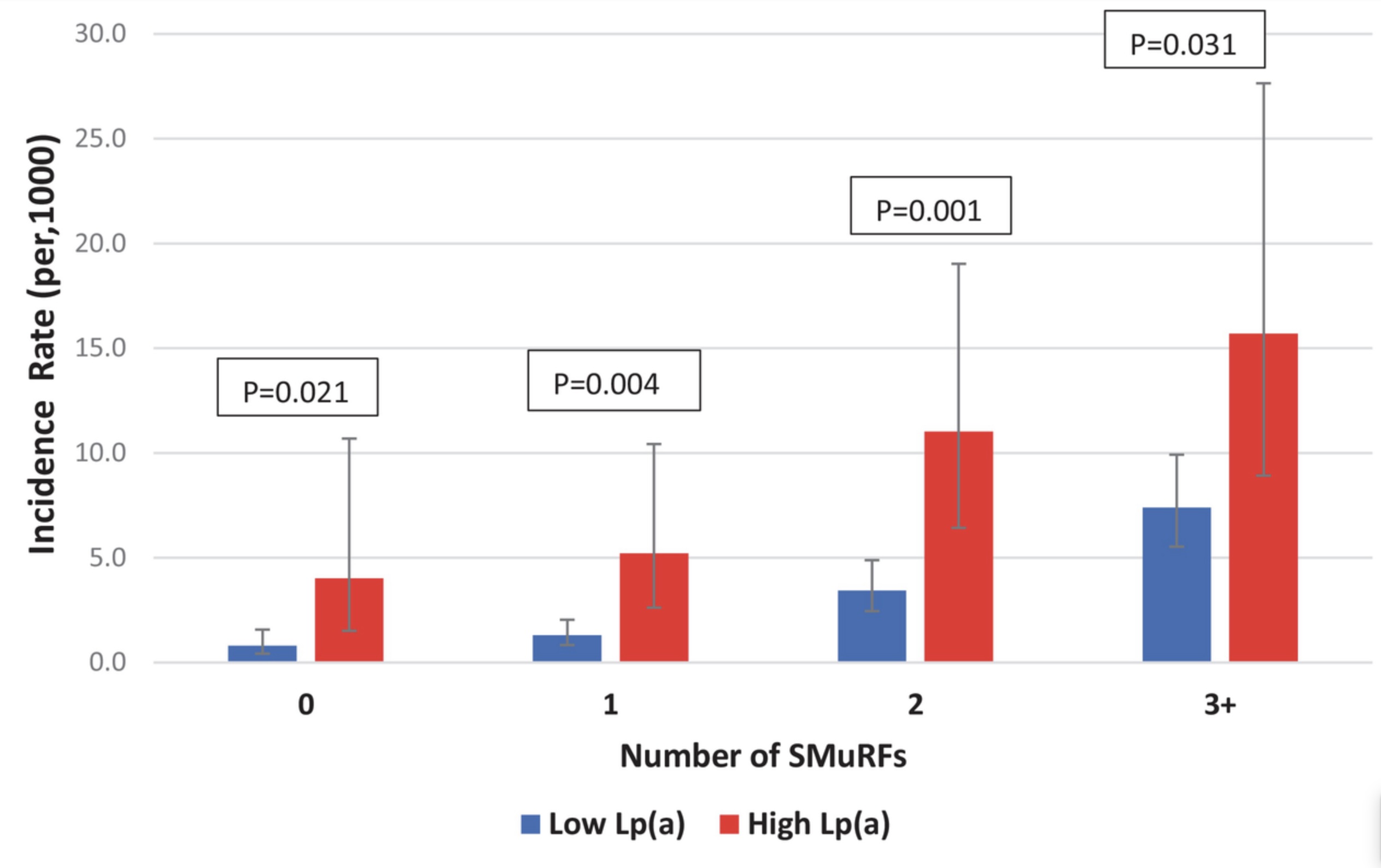

A 2024 study showed that high Lp(a) levels increase the risk of heart attacks more than standard modifiable risk factors (SMuRFs) which include diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and smoking.

The kicker: shorter lifespan

Genetic studies show that variants linked to high Lp(a) correlate to a shorter lifespan. When averaging together information from more than 100,000 people, the presence of an Lp(a) genetic variant caused an average decrease in lifespan of 1.5 years.[ref]

What is a high level of Lp(a)?

When you get your Lp(a) test results, how do you know if it is just slightly high or seriously scary?

Some researchers consider normal to be less than 50 mg/dl.[ref][ref] Another source says normal Lp(a) levels are less than 30 mg/dl (or 75 nmol/L).[ref]

Let’s look at how the risk increases with Lp(a) levels:

A study involving over 58,000 individuals in Denmark showed that major cardiovascular event rates (e.g. heart attacks) increased as Lp(a) levels increased. Lp(a) levels less than 10 mg/dL (18 nmol/L) had the lowest risk.[ref]

- 28% increased relative risk of major cardiac event with Lp(a) 10 to 49 mg/dL (18 – 105 nmol/L)

- 44% increased relative risk of major cardiac event with Lp(a) between 50 to 99 mg/dL (105–213 nmol/L)

- 114% increased relative risk of major cardiac event with Lp(a) ≥100 mg/dL (214 nmol/L)

For aortic valve stenosis, there is a 3-fold increase in relative risk for those with Lp(a) levels greater than 90 mg/dl.[ref]

A recent study in India showed that Lp(a) levels >50mg/dl (105 nmol/L) increased the risk of coronary artery disease in younger people by 2 to 3-fold.[ref]

Not all studies agree… as usual

An epidemiological study involving women found that Lp(a) levels were only important in cardiovascular disease if the women also had high cholesterol (>220 mg/dl).[ref]

A 2012 study in people with diabetes found that higher Lp(a) levels did not correlate with an increased risk of heart disease. There was no additional risk above and beyond the high risk from diabetes.[ref]

One problem with the epidemiological studies on Lp(a) is that most of them only last for 5 to 10 years, which may not be enough time to really determine causality.

Lipoprotein (a) Genotype Report

Normally the Genotype Report sections are only viewable by members. For this topic, I want everyone – member or not! – to go and check your genetic data to see if you carry the variants.

LPA gene: encodes lipoprotein(a). These first two genetic variants cover about 40% of the variation in Lp(a) levels — other, less common variants also raise Lp(a) levels.

Check your genetic data for rs3798220 I1891M (23andMe v4, v5, AncestryDNA):

- C/C: higher Lp(a) levels; increased risk for heart disease – 3.7x risk of aortic stenosis[ref][ref][ref] average Lp(a) of 153 mg/dL (women)[ref]

- C/T: higher Lp(a) levels; increased risk for heart disease, increased risk of aortic stenosis; average Lp(a) of 79.5 mg/dL (women)[ref]

- T/T: typical; average Lp(a) of 10 mg/dL (women)

Members: Your genotype for rs3798220 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs10455872 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: likely elevated Lp(a), increased risk for heart disease – 2x risk of aortic stenosis[ref][ref][ref]

- A/G: likely elevated Lp(a), increased risk for heart disease

- A/A: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs10455872 is —.

Additive risk: Studies show that carrying one risk allele for both of the above — compound heterozygous — also doubled the risk of aortic stenosis.[ref]

Other variants in the LPA gene show associations based on ancestry groups.

Check your genetic data for rs6415084 (AncestryDNA):

- T/T: higher Lp(a) levels, increased risk of heart disease (Chinese population group)[ref] no increased risk in Iranian or European Caucasian populations[ref][ref]

- C/T: higher Lp(a) levels, increased risk of heart disease (Chinese population group)

- C/C: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs6415084 is —.

If you have full genome testing, check for these other LPA gene variants as well:

- rs9457951 – this may be a better marker for African Americans [ref]

- rs6415085 – T allele linked to higher Lp(a)[ref]

Variants that lower Lp(a):

Check your genetic data for rs6919346 (23andMe v5; AncestryDNA):

Members: Your genotype for rs6919346 is —

Check your genetic data for rs41272114 (23andMe v4, v5):

Members: Your genotype for rs41272114 is —.

Note that genetic variants that hypercholesterolemia are also linked with higher Lp(a) levels. It makes sense that there would be more Lp(a) if your cholesterol levels are extremely high.

Lifehacks: Reducing high lipoprotein(a)

So what do you do if you carry the risk alleles for high Lp(a)? First, let’s look at testing options, and then I’ll explain multiple research-backed ways of lowering Lp(a) either with diet, natural supplements, or medications.

Knowledge is power here! You aren’t doomed to have a heart attack from your high Lp(a) levels, but you may need to take some action.

Lp(a) blood tests:

Talk to your doctor about getting an Lp(a) blood test done. It may be covered by insurance in your annual well-check, especially if you have a family history of early heart attacks. You can also get a test done for Lp(a) in the US without going through your doctor. For example, on UltaLabTests the Lp(a) test currently costs $29. There are other places online to order the Lp(a) test, and there’s also a new, at-home Lp(a) test for $99. (I haven’t used it, so check for reviews on it).

Seriously, the only way to know your current Lp(a) level is to get it tested. No excuses – you have lots of options for testing.

Now let’s take a look at ways you can lower your Lp(a) levels. Keep in mind that you can stack multiple interventions together – consider a dietary change plus supplements along with talking to your doctor about aspirin therapy or other medications.

Natural supplements for lowering Lp(a):

L-carnitine:

Multiple clinical trials have looked at the effect of l-carnitine supplementation on Lp(a) levels. A meta-analysis of the data showed an average decrease of about 9mg/dL (15 nmol/L) with l-carnitine supplements.[ref]

Ginkgo Biloba:

One study showed Ginkgo Biloba reduced Lp(a) levels. The study participants took 120mg twice a day, which resulted in a 23% decrease in Lp(a).[ref]

CoQ10:

Supplemental CoQ10 has been shown in randomized controlled trials to lower Lp(a) a little. The average of seven RCTs showed a decrease of 3.54 mg/dL (9 nmol/L).[ref] While a small reduction, it may be significant when combined with other interventions.

Related article: CoQ10: background science, mitochondrial energy, and genetic variants

Niacin:

Vitamin B3 – niacin – has been used for decades to lower the risk of heart disease. Studies show that 1 -3 g/day reduces Lp(a) levels by 30-40% on average.[ref][ref][ref] Most studies use the type of niacin that causes flushing.

A cautionary note with niacin: A 2024 study showed that higher levels of niacin consumption may increase the risk of heart disease in people with variants that increase niacin metabolites including 2PY and 4PY.

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACMSD | rs10496731 | T | -- | increased 4PY levels, increased risk of major cardiovascular events with higher niacin intake |

| ACMSD | rs6430553 | C | -- | increased 4PY levels, increased risk of major cardiovascular events with higher niacin intake |

| ACMSD | rs6729702 | G | -- | likely increased 4PY levels, increased risk of major cardiovascular events with higher niacin intake |

Berberine:

Berberine has been shown to decrease LDL cholesterol levels as well as Lp(a) levels a little bit.[ref][ref] Read through my article on berberine for more info as well as ways to increase absorption.

Dietary interventions for lowing Lp(a):

Plant-based diet:

A four-week plant-based intervention diet that included 16+ daily servings of fruits and vegetables reduced Lp(a) by 16% on average. The diet emphasized raw fruits and vegetables with small amounts of raw oats, seeds, buckwheat, and 1oz of meat per day permitted. Excluded were animal products, cooked foods, free oils, soda, alcohol, and coffee. The study notes that the amount of decrease in Lp(a) is similar to that of using niacin or a PCSK9 inhibitor.[ref]

Coconut oil instead of omega-6 oils:

An intervention study looking at fat in the diet found that a diet high in saturated fat from coconut oil decreased Lp(a) by 17 mg/L, while a diet high in poly-unsaturated fatty acids increased Lp(a) by 25 mg/L.[ref]

Lowering cholesterol:

Overall, lowering your LDL cholesterol numbers can help lower Lp(a) since Lp(a) is the carrier for LDL. Here is a good article on it from the Cleveland Clinic.

How do you lower your cholesterol with diet? That seems to be the million-dollar question. A more whole-food, plant-based diet, in comparison with a higher meat/fat-based diet, works to lower cholesterol for some people. You may need to try out several diets – Mediterranean, DASH, etc. – and test to see what works for your body.

Therapies to talk with your doctor about:

A couple of therapies for high Lp(a) have been well studied — as well as new drugs in trials to target it.[ref]

Aspirin:

A study of over 12,000 people over age 70 looked at the effect of 100mg of aspirin daily. The researchers found that those with the rs3798220 C allele were at an almost double risk of a ‘major adverse cardiovascular event’ in the placebo arm, but that risk was mitigated in those participants receiving aspirin.

A study of over 20,000 women looked at the effects of aspirin on heart disease. The study results showed that those women who carried one or two copies of the LPA risk allele cut their heart attack risk with aspirin therapy. (Women without elevated Lp(a) did not have a statistical benefit from aspirin.) The whole study is available here.

Talk with your doctor about aspirin therapy. This is an inexpensive option that is easy to implement, but you do need to make sure that you don’t have any bleeding risk factors or other counterindications.

Apheresis:

In apheresis, your blood is run through a machine to remove the LDL particles. It is considered effective but expensive and inconvenient.[ref]

PCSK9 inhibitors over statins:

Taking a statin has been shown to elevate Lp(a) levels a little bit. The newer cholesterol-lowering medications, PCSK9 inhibitors, have been shown to lower Lp(a) levels.[ref]

Keep up with new research:

Phase III clinical trials are underway for a new medication that targets Lp(a) with an antisense oligonucleotide.[ref] Your doctor will know if there are new options on the market for Lp(a), and then be sure to research and read through the clinical trial data to see if it is a good option for you.

Recap of your genes:

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPA | rs3798220 | C | -- | risk of elevated Lp(a), increased risk for heart disease (important) |

| LPA | rs10455872 | G | -- | risk of elevated Lp(a), increased risk for heart disease (important) |

| LPA | rs6919346 | T | -- | decreased Lp(a) |

| LPA | rs41272114 | T | -- | decreased Lp(a) |

| LPA | rs143431368 | C | -- | decreased Lp(a) |

| LPA | rs6415084 | T | -- | higher Lp(a) levels, increased risk of heart disease (Chinese population group); no increased risk in Iranian or European Caucasian populations |

Related Articles and Topics:

PCSK9 Gene: Understanding the variants that cause high or low LDL cholesterol

References:

Arsenault, Benoit J., et al. “Association of Long-Term Exposure to Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Levels With Parental Life Span, Chronic Disease–Free Survival, and Mortality Risk.” JAMA Network Open, vol. 3, no. 2, Feb. 2020, p. e200129. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0129.

Brix, Gitte Stokvad, et al. “Elevated lipoprotein (a) is independently associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis in de-novo patients with stable chest pain.” American Heart Journal (2025).

Chang, Xinxia, et al. “Lipid Profiling of the Therapeutic Effects of Berberine in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Journal of Translational Medicine, vol. 14, Sept. 2016, p. 266. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-0982-x.

Chapman, M. John, et al. “Niacin and Fibrates in Atherogenic Dyslipidemia: Pharmacotherapy to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk.” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 126, no. 3, June 2010, pp. 314–45. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.008.

Chasman, Daniel I., et al. “Polymorphism in the Apolipoprotein(a) Gene, Plasma Lipoprotein(a), Cardiovascular Disease, and Low-Dose Aspirin Therapy.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 203, no. 2, Apr. 2009, pp. 371–76. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.019.

Chen, Hao Yu, et al. “Association of LPA Variants With Aortic Stenosis: A Large-Scale Study Using Diagnostic and Procedural Codes From Electronic Health Records.” JAMA Cardiology, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 18–23. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4266.

Chmielewski, K. “[Clinical and bacteriological observations on the use of immediate prostheses made of quickly polymerizing methyl polymetacrylane].” Czasopismo stomatologiczne, vol. 19, no. 5, May 1966, pp. 549–53.

Clarke, Robert, et al. “Genetic Variants Associated with Lp(a) Lipoprotein Level and Coronary Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 361, no. 26, Dec. 2009, pp. 2518–28. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0902604.

Emdin, Connor A., et al. “Phenotypic Characterization of Genetically Lowered Human Lipoprotein(a) Levels.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 68, no. 25, Dec. 2016, pp. 2761–72. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.033.

Enas, Enas A., et al. “Lipoprotein(a): An Independent, Genetic, and Causal Factor for Cardiovascular Disease and Acute Myocardial Infarction.” Indian Heart Journal, vol. 71, no. 2, Mar. 2019, pp. 99–112. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2019.03.004.

Erhart, Gertraud, et al. “Genetic Factors Explain a Major Fraction of the 50% Lower Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations in Finns.” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 38, no. 5, May 2018, pp. 1230–41. ahajournals.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.310865.

Franchini, Massimo, et al. “Lipoprotein Apheresis for the Treatment of Elevated Circulating Levels of Lipoprotein(a): A Critical Literature Review.” Blood Transfusion, vol. 14, no. 5, Sept. 2016, pp. 413–18. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2450/2015.0163-15.

Hanssen, Ruth, and Ioanna Gouni-Berthold. “Lipoprotein(a) Management: Pharmacological and Apheretic Treatment.” Current Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 10, 2017, pp. 957–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867324666170112110928.

Joshi, Parag H., et al. “Do We Know When and How to Lower Lipoprotein(a)?” Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 12, no. 4, Aug. 2010, pp. 396–407. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-010-0077-6.

Kamstrup, Pia R., et al. “Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and Risk of Aortic Valve Stenosis in the General Population.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 63, no. 5, Feb. 2014, pp. 470–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.038.

Kronenberg, F., and G. Utermann. “Lipoprotein(a): Resurrected by Genetics.” Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 273, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 6–30. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02592.x.

Kronenberg, Florian. “Prediction of Cardiovascular Risk by Lp(a) Concentrations or Genetic Variants within the LPA Gene Region.” Clinical Research in Cardiology Supplements, vol. 14, no. 1, Apr. 2019, pp. 5–12. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11789-019-00093-5.

Laschkolnig, Anja, et al. “Lipoprotein (a) Concentrations, Apolipoprotein (a) Phenotypes, and Peripheral Arterial Disease in Three Independent Cohorts.” Cardiovascular Research, vol. 103, no. 1, July 2014, pp. 28–36. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvu107.

Li, Yonghong, et al. “Genetic Variants in the Apolipoprotein(a) Gene and Coronary Heart Disease.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics, vol. 4, no. 5, Oct. 2011, pp. 565–73. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.959601.

Najjar, Rami S., et al. “Consumption of a Defined, Plant‐based Diet Reduces Lipoprotein(a), Inflammation, and Other Atherogenic Lipoproteins and Particles within 4 Weeks.” Clinical Cardiology, vol. 41, no. 8, Aug. 2018, pp. 1062–68. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23027.

PhD, Chris Masterjohn. “026: The 5 Best Ways to Lower Cholesterol Naturally.” Harnessing the Power of Nutrients, 9 May 2017, https://chrismasterjohnphd.substack.com/p/026-the-5-best-ways-to-lower-cholesterol.

Qi, Qibin, et al. “Genetic Variants, Plasma Lipoprotein(a) Levels, and Risk of Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality among Two Prospective Cohorts of Type 2 Diabetes.” European Heart Journal, vol. 33, no. 3, Feb. 2012, pp. 325–34. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr350.

Risch, S. C., et al. “Multiendocrine Assessment in the Dexamethasone Suppression Test.” Psychopharmacology Bulletin, vol. 22, no. 3, Jan. 1986, pp. 913–16.

Rodríguez, M., et al. “Reduction of Atherosclerotic Nanoplaque Formation and Size by Ginkgo Biloba (EGb 761) in Cardiovascular High-Risk Patients.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 192, no. 2, June 2007, pp. 438–44. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.02.021.

Ronald, James, et al. “Genetic Variation in LPAL2 , LPA , and PLG Predicts Plasma Lipoprotein(a) Level and Carotid Artery Disease Risk.” Stroke, vol. 42, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 2–9. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.591230.

Song, Zi-Kai, et al. “LPA Gene Polymorphisms and Gene Expression Associated with Coronary Artery Disease.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2017, 2017, p. 4138376. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4138376.

Viney, Nicholas J., et al. “Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting Apolipoprotein(a) in People with Raised Lipoprotein(a): Two Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Ranging Trials.” Lancet (London, England), vol. 388, no. 10057, Nov. 2016, pp. 2239–53. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31009-1.

Vogt, Anja. “Lipoprotein(a)-Apheresis in the Light of New Drug Developments.” Atherosclerosis. Supplements, vol. 30, Nov. 2017, pp. 38–43. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2017.05.025.

Wang, Hui, et al. “Berberine Modulates LPA Function to Inhibit the Proliferation and Inflammation of FLS-RA via P38/ERK MAPK Pathway Mediated by LPA1.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2019, Nov. 2019, p. e2580207. www.hindawi.com, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2580207.

“Why Would My Doctor Order a Lipoprotein(a) Blood Test?” Cleveland Clinic, 11 Dec. 2019, https://health.clevelandclinic.org/why-would-my-doctor-order-a-lipoproteina-blood-test/.