Key Takeaways:

~ The CYP450 family of genes encodes enzymes that break down (metabolize) foreign substances, like medications and toxicants.

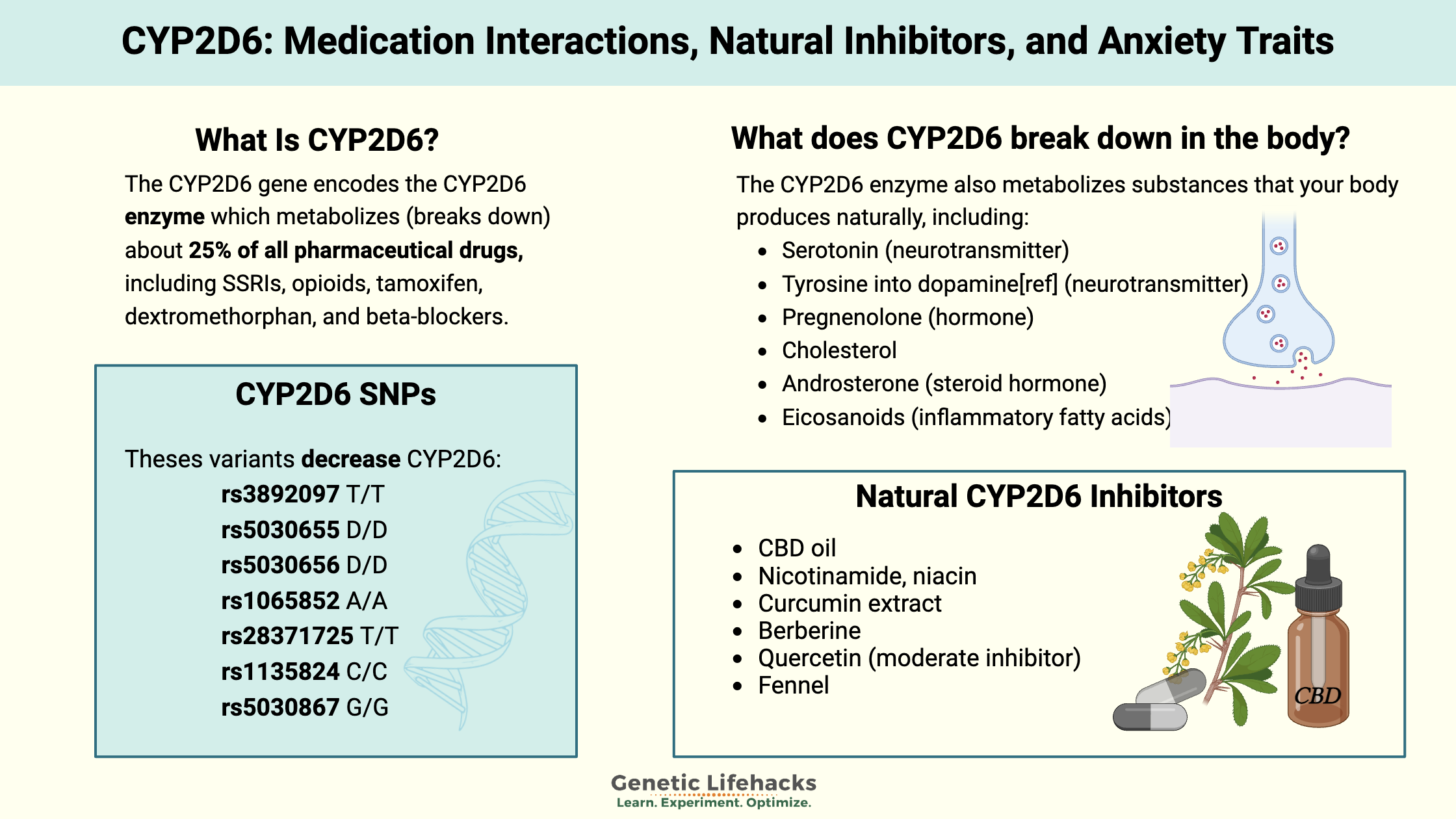

~ CYP2D6 metabolizes about 25% of prescription drugs.

~ Genetic variants in CYP2D6 affect how medications work for an individual.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

CYP2D6: Breaking down medications

Say you aren’t feeling well, have had a cold for a week, and can’t sleep… you’re just plain miserable. In your sleep-deprived state, you decide to take some Nyquil (or another cough syrup containing dextromethorphan). Some people may get relief and finally get some sleep. Others may wake up the next morning feeling like they were hit by a truck.

This example is just one of many medications metabolized by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Many genetic variants impact the function of CYP2D6, causing a wide variety of reactions to some commonly used medications.

Medications: The CYP2D6 enzyme metabolizes (breaks down) about 25% of pharmaceutical drugs, including SSRIs, opioids, tamoxifen, dextromethorphan, and beta-blockers.

Which drugs are metabolized by CYP2D6?

Common prescription medications that are metabolized by CYP2D6 include:

- Dextromethorphan (cough syrup)

- Hydrocodone (pain)

- Methadone

- Tamoxifen (breast cancer, estrogen blocker)

- Pimozide (Tourette’s medication)

- Metoprolol (beta-blocker)

- Propranolol (beta-blocker)

- Risperidone (schizophrenia, bipolar medication)

You can find a full list with details at PharmGKB.

Environmental toxicants metabolized by CYP2D6:

Many chemicals and toxicants that we are regularly exposed to are broken down by CYP450 enzymes. For many substances, more than one CYP enzyme can be involved in the metabolism.

Some of the toxicants that are metabolized (partially or fully) by or impact CYP2D6 include:

- Organophosphate and organochlorine pesticides [ref]

- Fipronil (pesticide)[ref]

- Carbendazim (fungicide)[ref]

Endogenous (made in the body) substances metabolized by CYP2D6:

The CYP2D6 enzyme also metabolizes substances that your body produces naturally, including[ref][ref]

- Serotonin (neurotransmitter)

- Tyrosine into dopamine[ref] (neurotransmitter)

- Pregnenolone (hormone)

- Cholesterol

- Androsterone (steroid hormone)

- Eicosanoids (inflammatory fatty acids)

It’s important to keep these ongoing, natural functions of CYP2D6 in mind when you are looking at your genotype report (below) and also when you are taking supplements or medications. For example, if you have variants that decrease the function of CYP2D6, your system is used to that and keeps the endogenous substrates at the right level. But if you add in several CYP2D6 inhibitors, organophosphate pesticides, or drugs that utilize it, you may not have the same reserve function for your endogenous substrates that other people have.

Speeding up and slowing down enzyme function:

Several important variants in the CYP2D6 gene can cause the enzyme to function differently — either by speeding up or slowing down the rate by which the medications break down.

- A fast CYP2D6 enzyme function is usually called an ‘extensive metabolizer‘

- Slow (or no) enzyme function is referred to as a ‘poor metabolizer‘.

A fast or ultrarapid metabolizer will clear the drug from their system more rapidly. It can mean that the drug has less of an effect than expected.

Pro-drugs: For a few medications, it is the metabolite (or what the drug is converted into) that gives the effect. For these types of pro-drugs, an extensive metabolizer can have a more intense effect from the drug.

Slower enzyme function, for many drugs, can mean that the medication sticks around in the body longer than normal. It may affect how much you need to take or how often to take the drug.

A variant that slows down the CYP2D6 isn’t always bad. Being a poor metabolizer may reduce the risk of cancers such as bladder or lung cancer.

On the other hand, it also may significantly increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease for those exposed to higher levels of pesticides.[ref]

Knowing whether you’re a fast or slow metabolizer may make it easier to find the proper dosage of certain medications. But you also need to understand how the drug works in the body:

- Some drugs, such as tamoxifen, need to be metabolized to their active form by CYP2D6 to work.

- Other drugs are turned into their inactive form by CYP2D6.

Remember that many drugs, toxins, and endogenous substances can be metabolized using multiple CYP enzymes. Thus, many drugs metabolized by CYP2D6 may also be broken down with other enzymes.

Anxiety traits and CYP2D6 variants:

I mentioned above that CYP2D6 is involved in[ref][ref]

- The metabolism of tyrosine to dopamine.

- The turnover rate of serotonin.

- The metabolism of anandamide, which binds to the cannabinoid receptor.

With the impact on neurotransmitters, researchers subsequently discovered that CYP2D6 genetic variants are linked to personality traits. For example, several studies show that CYP2D6 poor metabolizers are more likely to score lower in socialization and higher in anxiety symptoms.[ref]

While the information on possible links to personality traits is interesting, the research also points out that medications that utilize CYP2D6 may also (somewhat) affect your mood.

Again, you need to look at your genetic variants — along with any exposure to pesticides metabolized by CYP2D6 plus any natural supplements or medications you take — to give you the whole picture.

Pharmacogenomic Testing:

Pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing is a type of genetic test and report created by a company that specializes in the pharmacology and genetics of drug response. There are a number of companies that offer PGx testing, including UGenome. Your doctor may have a suggested company or an option that would work with your insurance.

While you can learn about the more common CYP2D6 variants below, it isn’t as complete as PGx testing.

CYP2D6 Genotype Report:

Lifehacks:

The main takeaway is that if you carry a non-functioning or decreased response variant, you need to be aware that drugs metabolized through CYP2D6 may not work normally for you.

- It could mean varying the dosage or timing.

- Or you may need to discuss alternative medications with your doctor.

Talk with your doctor or pharmacist if you have questions.

Only part of the picture:

There are rare mutations that are not in DTC genetic tests, and the genotype report section above does not contain all possible CYP2D6 mutations. You can’t use it to completely rule out a problem. However, clinical genetic testing is available through your doctor to check gene-drug interactions.

Many medications are metabolized using multiple CYP genes. Here are other genes to check:

Natural CYP2D6 Inhibitors:

Related Articles and Topics:

References:

Al-Jenoobi, Fahad Ibrahim, et al. “Effect of Curcuma Longa on CYP2D6- and CYP3A4-Mediated Metabolism of Dextromethorphan in Human Liver Microsomes and Healthy Human Subjects.” European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, vol. 40, no. 1, Mar. 2015, pp. 61–66. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-014-0180-2.

Chavan, Bir S., et al. “A Prospective Study to Evaluate the Effect of CYP2D6 Polymorphism on Plasma Level of Risperidone and Its Metabolite in North Indian Patients with Schizophrenia.” Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, vol. 40, no. 4, Aug. 2018, pp. 335–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_83_18.

Cheng, Jie, et al. “Potential Role of CYP2D6 in the Central Nervous System.” Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems, vol. 43, no. 11, Nov. 2013, pp. 973–84. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3109/00498254.2013.791410.

González, Idilio, et al. “Relation between CYP2D6 Phenotype and Genotype and Personality in Healthy Volunteers.” Pharmacogenomics, vol. 9, no. 7, July 2008, pp. 833–40. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2217/14622416.9.7.833.

Guo, Ying, et al. “Repeated Administration of Berberine Inhibits Cytochromes P450 in Humans.” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 68, no. 2, Feb. 2012, pp. 213–17. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-1108-2.

Langhammer, Astrid Jordet, and Odd Georg Nilsen. “In Vitro Inhibition of Human CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 by Six Herbs Commonly Used in Pregnancy.” Phytotherapy Research: PTR, vol. 28, no. 4, Apr. 2014, pp. 603–10. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5037.

Lu, Jin, et al. “The Roles of Apolipoprotein E3 and CYP2D6 (Rs1065852) Gene Polymorphisms in the Predictability of Responses to Individualized Therapy with Donepezil in Han Chinese Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease.” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 614, Feb. 2016, pp. 43–48. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2015.12.062.

Madeira, Maria, et al. “The Effect of Cimetidine on Dextromethorphan O-Demethylase Activity of Human Liver Microsomes and Recombinant CYP2D6.” Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals, vol. 32, no. 4, Apr. 2004, pp. 460–67. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.32.4.460.

Nebert, Daniel W., et al. “Human Cytochromes P450 in Health and Disease.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 368, no. 1612, Feb. 2013, p. 20120431. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0431.

NM_000106.5(CYP2D6):C.506-1G>A AND Not Provided – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000342450.1/. Accessed 24 Aug. 2022.

Peñas-LLedó, Eva M., and Adrián LLerena. “CYP2D6 Variation, Behaviour and Psychopathology: Implications for Pharmacogenomics-Guided Clinical Trials.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 77, no. 4, Apr. 2014, pp. 673–83. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12227.

“PharmGKB.” PharmGKB, https://www.pharmgkb.org/gene/PA128/clinicalAnnotation. Accessed 24 Aug. 2022.

Rastogi, Himanshu, and Snehasis Jana. “Evaluation of Inhibitory Effects of Caffeic Acid and Quercetin on Human Liver Cytochrome P450 Activities.” Phytotherapy Research: PTR, vol. 28, no. 12, Dec. 2014, pp. 1873–78. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5220.

Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme, et al. “Pharmacogenomic Diversity among Brazilians: Influence of Ancestry, Self-Reported Color, and Geographical Origin.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 3, Nov. 2012, p. 191. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2012.00191.

Taylor, Christopher, et al. “A Review of the Important Role of CYP2D6 in Pharmacogenomics.” Genes, vol. 11, no. 11, Oct. 2020, p. 1295. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111295.

Van Nieuwerburgh, Filip C. W., et al. “Response to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in OCD Is Not Influenced by Common CYP2D6 Polymorphisms.” International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, vol. 13, no. 1, Nov. 2009, pp. 345–48. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3109/13651500902903016.

Wang, Danxin, et al. “Common CYP2D6 Polymorphisms Affecting Alternative Splicing and Transcription: Long-Range Haplotypes with Two Regulatory Variants Modulate CYP2D6 Activity.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 268–78. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddt417.

Werner, Ulrike, et al. “Celecoxib Inhibits Metabolism of Cytochrome P450 2D6 Substrate Metoprolol in Humans.” Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, vol. 74, no. 2, Aug. 2003, pp. 130–37. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00120-6.

Yamaori, Satoshi, et al. “Cannabidiol, a Major Phytocannabinoid, As a Potent Atypical Inhibitor for CYP2D6.” Drug Metabolism and Disposition, vol. 39, no. 11, Nov. 2011, pp. 2049–56. dmd.aspetjournals.org, https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.111.041384.

Yu, Ai-Ming, et al. “Regeneration of Serotonin from 5-Methoxytryptamine by Polymorphic Human CYP2D6.” Pharmacogenetics, vol. 13, no. 3, Mar. 2003, pp. 173–81. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.fpc.0000054066.98065.7b.

Originally published 6/2015. Revised on 4/26/19.