Key takeaways:

~ Researchers are actively trying to figure out how and why we age and why some people live longer without health problems.

~ About 50% of the variation in lifespan is due to genetic variants.

~ There are also genetic variants linked to a longer healthspan.

Understanding the genes linked to healthspan shows which pathways are actually important. The Lifehacks section includes research-backed ways to mimic the effect of ‘good’ longevity genes.

Longevity: Living a long and healthy life

The average lifespan in the US is around 80. We generally accept it as ‘just the way it is’.

But… some people live to 100+ and are still relatively healthy. A few people live to 110 or 120.

When you look at the animal kingdom, most lab mice and rats live for 2 to 3 years. It is in line with other small mammals — except for the naked mole rat, which lives over 30 years in captivity without any age-related declines.[ref]

What is the difference? Why do some people live 20 or 30 years longer without dying of the chronic diseases of aging (heart disease, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s)?

You may immediately assume that everyone who lives longer did everything right- exercised, meditated, ate the very best diet, etc. – but that isn’t necessarily the case. Researchers estimate that about 50% of the variation in lifespan is due to genetics.[ref]

What does it take to live a long, healthy life? Avoiding smoking, not drinking too much alcohol, and not getting cancer are important for the first 80 years. Beyond that, genetics becomes really important.

Looking at the genetic variants in long-lived humans as well as investigating long-lived animals, like the naked mole-rat, helps us understand what is important for extending healthspan and lifespan.

What can genetics tell us about longevity?

There are several ways to approach health problems:

- Mitigate the symptoms (take a pill that causes the symptom to go away, the way many doctors treat health issues today)

- Figure out what causes the symptoms on a population-wide level (e.g. epidemiological studies that show excessive soda consumption linked to metabolic syndrome)

- Try to determine the ‘root cause’ by looking at various metabolic pathways (for example, a deficiency in vitamin B12 is one cause of peripheral neuropathy)

- Study the genetic variants in people with a condition to see which genetic variants cause the problem:

- focus on known genetic variants that researchers suspect should cause the condition

- investigate the interaction between specific genetic variants and environmental conditions

- look at the whole genome of a large population group to see if people with a certain condition have statistically different levels of a genetic variant

Researchers have used all of these methods to treat the diseases of aging. But the most exciting new research comes from looking at the genetic variants that cause the ‘condition’ of longevity.

The outliers, the centenarians living to 100, come from all types of backgrounds – different lifestyles, different ways of eating, and different environmental factors. It makes epidemiological studies difficult.

However, centenarians have common genetic variants that can be determined with a whole lot of computing power. Longevity genes come to light with genome-wide association studies that look at vast amounts of genetic data.

Putting longevity statistics into perspective:

Before we get into the genetic variants that cause a statistical increase in the likelihood of living longer, let’s take a quick look at the baseline numbers.

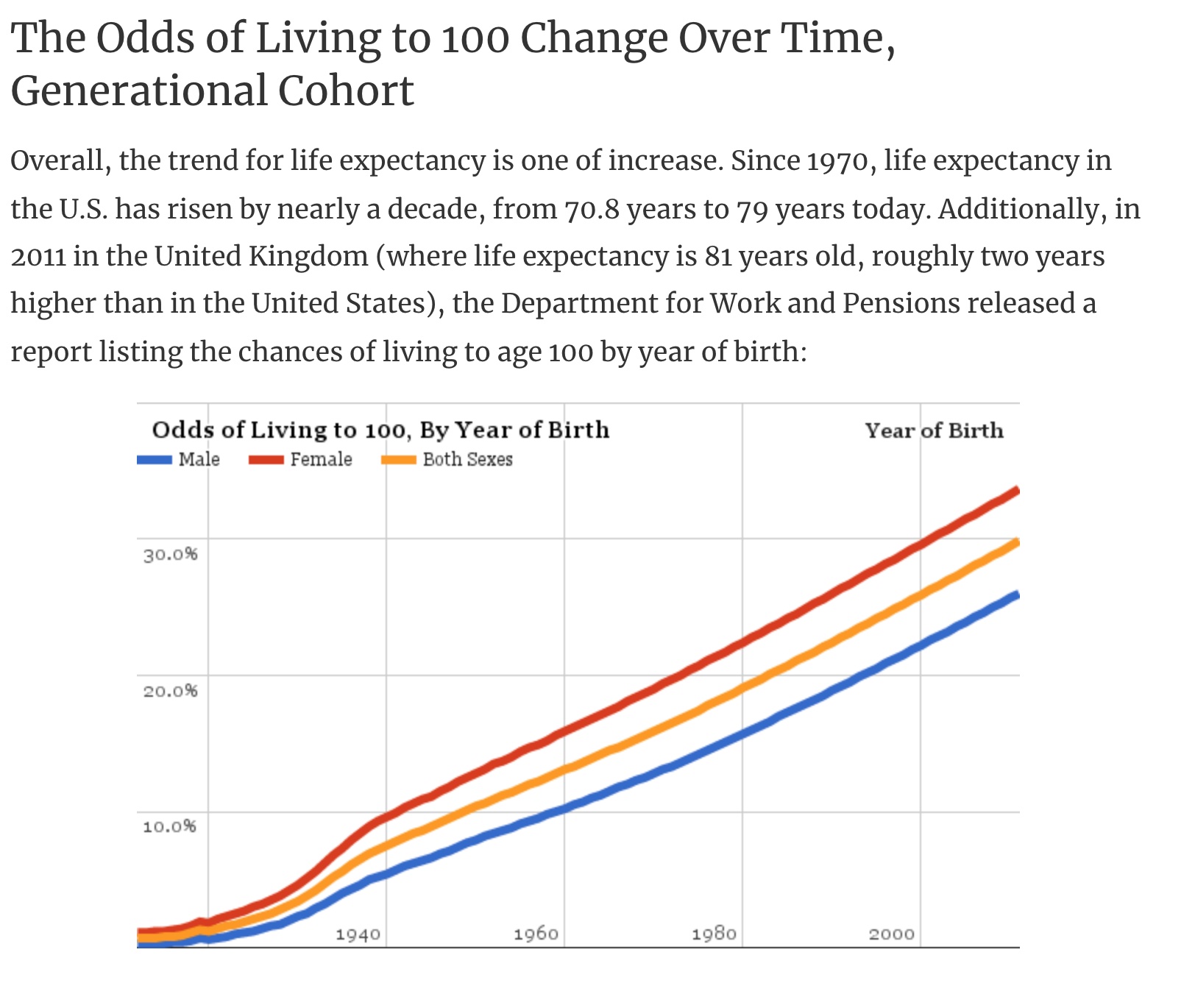

Someone born a hundred years ago has less than a 1% chance of being alive today. In contrast, if you are a female born in 1973, your odds of living to 100 are 20%.

Keep in mind, though, that these statistics are about the population in general rather than you as an individual. While genetics does play a role in how long you live, many other health, environmental, and lifestyle factors are also important.

Causes of mortality:

Understanding what causes most deaths can also guide us, to some extent, in our understanding of longevity.

In 2018, there were 2.8 million deaths in the US. The ten leading causes of death in the US are heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, lower respiratory diseases, stroke, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, kidney disease, and suicide.[ref]

What needs to go on at a cellular level for healthy aging?

Studies of centenarians show that their offspring also tend to live longer than their peers – and also have fewer of the diseases of aging. These studies also show that there isn’t just one thing, or a couple of things, that are different for centenarians. Instead, there is a lot of heterogeneity, small differences that affect many different aspects of health.[ref]

Let’s take a look at some of the causes of aging:

Cells accumulate damage and get replaced all the time, at all ages. It is just part of the way that the body works. The cells in your intestines turn over fairly quickly, with a cellular turnover rate of 2-6 days. Fat cells turnover every eight years. In contrast, most brain cells and heart cells are never replaced.[ref][ref]

You don’t want too much cell death or out-of-control cellular growth. Cells dying, getting cleared out, and replacing the need to all work in concert.

Avoiding cancer:

When cells divide, the DNA needs to be copied correctly for the newly created cells. Errors in the DNA copy mechanism occur, and if the errors aren’t corrected, that cell may need to go through apoptosis (cell death). DNA errors that occur in specific genes cause cancer… Avoiding cancer is important for longevity. As we age, the odds of DNA errors increase due to various insults such as toxins that cause oxidative stress in the cell.

Telomeres:

When DNA is replicated, the end of the DNA strand is not included in the new cell. To compensate for this, at the end of each chromosome is a region of repeated nucleotides called the telomere. It protects the genes from getting cut off during replication. As cells replicate multiple times, the telomeres shorten, eventually getting too short and halting cell division. At this point, the cell goes into senescence and eventually cell death.

Telomere shortening isn’t as straightforward, though, as ‘replicate x number of times and stop’. Telomeres can lengthen again with the telomerase enzyme, coded for by the TERT gene. Both internal and external stress (toxin exposure) can decrease telomerase.

While it sounds like telomerase is the key to immortality (and it is for some cancer cell lines), telomerase is almost non-existent in certain body tissues, including the kidneys, blood vessels, liver, skin, and peripheral leukocytes. Genetic variants in the TERT gene (not covered by 23andMe or Ancestry) were recently linked to human longevity.[ref] (Note how well these tissues correspond well to the causes of mortality – cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, immune function).

Metabolism:

One way to increase lifespan in lab animals is to decrease calories.

Restricting calories works great for short-lived animals, but it doesn’t seem to be all that effective for humans and other long-lived mammals. But, this does point to metabolism being intertwined with longevity in some ways. A couple of the theoretical reasons why calorie restriction increases lifespan include changes to IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) and autophagy.[ref]

IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) synthesizes in the liver. The level of growth hormone in the body is one of the main regulators, causing the liver to increase or decrease IGF1 production. IGF1 binds to its receptor on cell membranes throughout different tissues in the body. This binding activates many different actions inside of a cell that are mostly related to being pro-growth. Lower levels of IGF1 are linked with extended lifespan in a lot of species, but there is a big tradeoff, at least in humans…IGF1 is really important for cognitive function and brain plasticity.[ref]

Longevity and lifespan are often about tradeoffs — those things that are beneficial for initial growth and development can become problematic later in life. IGF1 epitomizes this concept of tradeoffs, at least to some degree.

Autophagy:

Autophagy is the cellular cleaning up of damaged organelles and recycling of cellular waste. It is also important for targeting intracellular microbes and misfolded proteins.[ref]

Alzheimer’s:

Genetic variants in the APOE gene which increase the risk of Alzheimer’s also decrease longevity due to death from Alzheimer’s.

Excessive inflammatory response:

Inflammation is essential for fighting off a bacterial infection when you get a cut. However, the flip side of the inflammatory response is that increased inflammation is linked to many chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and bone fragility. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are linked with decreased longevity.[ref]

Response to toxins:

Genetic variants influence how environmental toxins impact a person. Some of us are more resilient and can easily metabolize and get rid of various toxicants. Others may have a variant negatively impacting a detoxification pathway for a certain toxicant — which only matters if the person becomes exposed to that substance.

Genetic research shows links between CYP2B6 variants and longevity. The CYP2B6 enzyme is important in the metabolism of many drugs (including statins) as well as pesticides and insecticides (pyrethroids and DEET). Interestingly, women have higher CYP2B6 levels than men. It could also be that people with altered drug metabolism are statistically more likely to survive cancer and thus influence longevity statistics.[ref][ref]

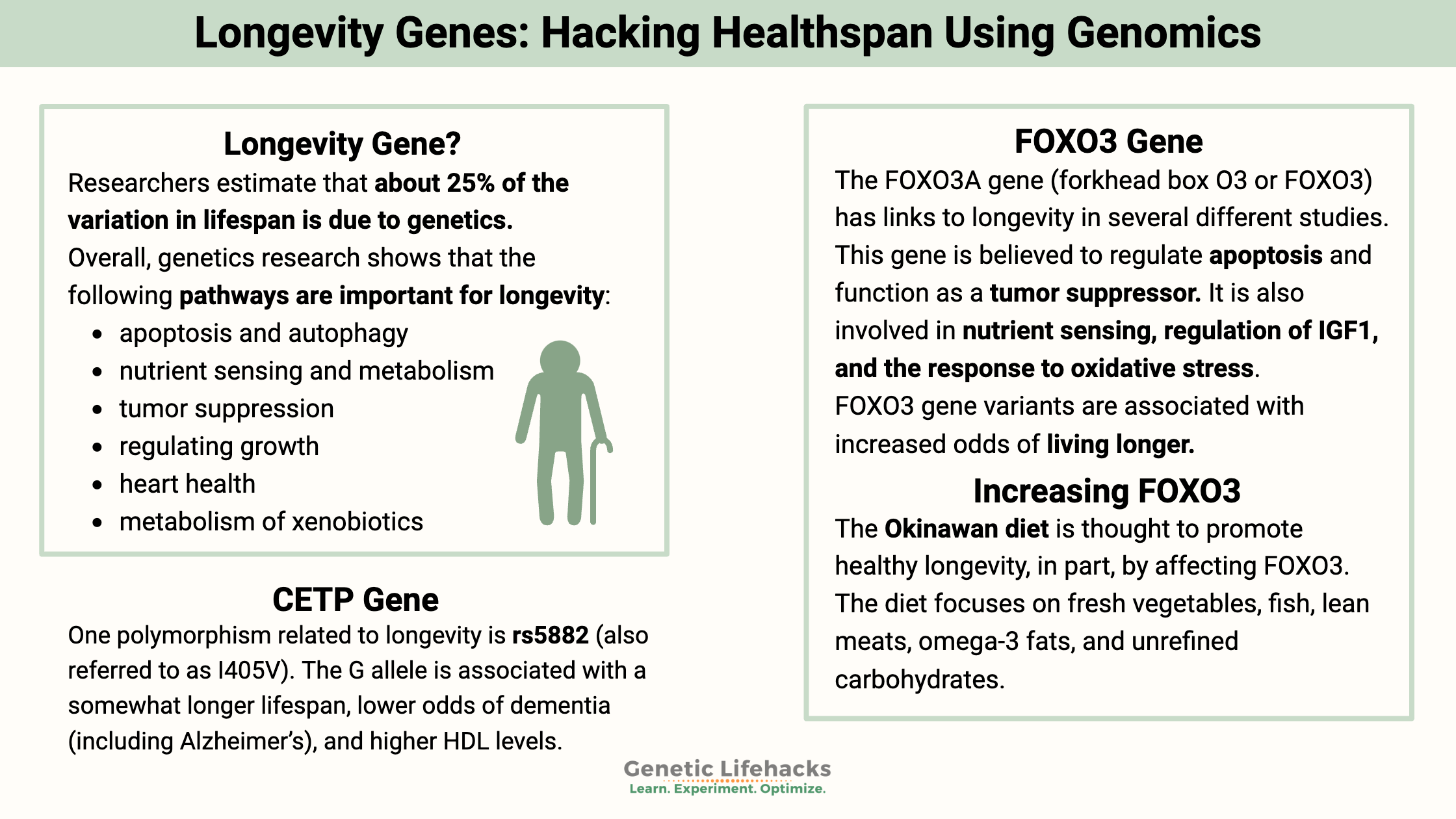

Overall, genetics research shows that the following pathways are important for longevity:

- apoptosis and autophagy

- nutrient sensing and metabolism

- tumor suppression

- regulating growth

- heart health

- metabolism of xenobiotics

Next, let’s get into the variants you can check for with your genetic data.

Longevity Genotype Report:

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Let’s get more specific here on the genes that have been identified as being important for longevity.

FOXO3 gene: The FOXO3A gene (forkhead box O3 or FOXO3) has links to longevity in several different studies. This gene is believed to regulate apoptosis (cell death) and function as a tumor suppressor. Also, it is involved in nutrient sensing, regulation of IGF1, and the response to oxidative stress.[ref][ref]

Check your genetic data for rs2802292 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: increased odds of living longer (1.5 to 2.75-fold increased odds)[ref][ref]; lower blood glucose levels in women[ref]; increased FOXO3[ref] lower inflammatory cytokines in older adults[ref]

- G/T: increased odds of living longer; lower inflammatory cytokines in older adults

- T/T: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs2802292 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs1935949 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: increased longevity for women[ref]

- A/G: increased longevity for women

- G/G: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs1935949 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs479744 (AncestryDNA only):

- T/T: somewhat higher probability of increased longevity[ref]

- G/T: somewhat higher probability of increased longevity

- G/G: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs479744 is —.

IGF1R gene: The IGF1R gene codes for the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. IGF1 is a hormone that signals growth and anabolic activity. Growth hormone levels generally fall as we age.

Check your genetic data for rs2229765 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

Members: Your genotype for rs2229765 is —.

CETP Gene: Another gene related to longevity is the CETP gene (cholesteryl ester transfer protein), which involves exchanging triglycerides with cholesteryl esters. One polymorphism related to longevity is rs5882 (also referred to as I405V). The G allele is associated with a somewhat longer lifespan, lower odds of dementia (including Alzheimer’s), and higher HDL levels.[ref]

Check your genetic data for rs5882 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: longer lifespan, higher HDL cholesterol, significantly decreased risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s[ref][ref]

- A/G: longer lifespan, higher HDL cholesterol

- A/A: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs5882 is —.

IMPK gene: The IPMK gene provides the instructions for the inositol polyphosphate multikinase (IMPK) enzyme. IMPK converts inositol triphosphate (IP3) to IP4 and IP4 to IP5, which act as signaling molecules that increase intracellular calcium ions (Ca2+ ). This impacts cell proliferation and mTOR, among other functions. It is also important in the brain in neural plasticity as well as in regulating Toll-like receptors in the immune system. (Note that other variants in this gene not included in 23andMe or AncestryDNA data also have links to longevity.)[ref]

Check your genetic data for rs6481383 (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/T: most common genotype

- T/T: increased longevity (women only)[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs6481383 is —.

TP53 gene: This gene encodes a tumor suppressor protein. With cancer being one of the top causes of death, it is obvious that not getting cancer gives a longevity benefit.

Check your genetic data for rs1042522 (23andMe v4, v5):

- G/G: increased longevity (possibly due to increased cancer survival)[ref]

- C/G: slightly increased longevity

- C/C: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs1042522 is —.

IL-6 Gene: Interleukin-6 is an inflammatory cytokine. While inflammation is good when you need to fight off a pathogen, an excessive inflammatory response is detrimental, especially in regard to chronic inflammation.

Check your genetic data for rs2069837 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: typical

- A/G: increased IL-6 response

- G/G: increased IL-6 response to inflammatory stimuli; fewer centenarians carry this genotype.[ref][ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs2069837 is —.

CYP2B6 gene: This gene codes for a phase I detoxification enzyme that is important for the metabolism of various drugs (including cancer drugs) as well as being active in cholesterol synthesis.[ref]

Check your genetic data for rs3745274 (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: typical

- G/T: typical

- T/T: decreased CYP2B6 enzyme, genotype less likely to be found in elderly, possible longevity disadvantage due to cancer risk or toxicant exposure[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs3745274 is —.

COMT gene: The COMT gene codes for a phase II enzyme involved in the metabolism of estrogen, catecholamine neurotransmitters, and more.

Check your genetic data for rs4680 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: genotype more likely to be found in the elderly, possible longevity advantage[ref]

- A/G: typical longevity

- G/G: typical longevity

Members: Your genotype for rs4680 is —.

What have I left out?

It’s important to note that not all studies agree on longevity benefits, and other popular genetic reports may include genes that I have chosen to leave out.

For example, I’ve left out AKT1, which is included in other websites’ genetic reports. In some studies, the minor allele of AKT1 rs3803304 (G allele) was initially linked to a shorter lifespan.[ref] Other studies, though, failed to replicate the initial studies.[ref] Similarly, I’ve chosen not to include APOC3 (listed in other genetics reports) because the initial research could not be replicated.[ref]

Why do studies differ? Environmental factors play a role. For example, a genetic variant important in a Greek population eating a Mediterranean diet may not be important in an African population group eating a different indigenous diet. Likewise, other genetic factors common to a population’s heritage may also play a role.

Lifehacks: Diet, natural supplements, and lifestyle changes for longevity

While we can’t (yet) be like naked-mole rats, there are ways of influencing the genetic pathways linked with longevity.

Important here is not whether you carry the genetic variants linked to longevity, but instead, knowing which biological systems to target for healthspan.