A decades-old diabetes drug now holds promise for increasing healthspan. Research shows that metformin may reduce the risk of some of the diseases of aging, thus increasing the number of years someone is healthy.

What is metformin?

Metformin, also known as Glucophage, is the most commonly prescribed medication for reducing blood glucose levels. Metformin prescriptions target people with diabetes, prediabetes, and sometimes PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome).

Beyond diabetes, there are also many studies pointing to other positive benefits of metformin as a longevity or healthy aging medication.

How does metformin work?

Metformin has a couple of mechanisms of action:

- It decreases glucose production in the liver, which is especially important for overnight blood glucose regulation.

- It increases the uptake of glucose in muscles and other parts of the body.

Let’s take a close look at all three of these actions of metformin:

Decreases glucose production in the liver:

When glucose levels in the body fall, such as when fasting or even overnight when sleeping, the liver can produce glucose through a process called gluconeogenesis. This keeps glucose levels in the right range all day and night for people without diabetes.

Research on exactly how metformin decreases gluconeogenesis (glucose production) in the liver isn’t fully elucidated. There seem to be several possibilities:

- First, metformin may act partially in the mitochondria, inhibiting complex I in the electron transfer chain. This would alter the ratio of AMP (adenosine monophosphate) to ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which triggers AMPK. AMPK does a bunch of things, including decreasing gluconeogenesis.[ref]

- Second, metformin may be altering the way that lactate is being used for energy in the mitochondria. A January 2020 paper contends that metformin works by decreasing glucose 6-phosphate (G6P).[ref][ref]

New research also questions whether metformin reduces glucose production in the liver for people without type 2 diabetes. The studies indicate that glucose production in the liver may not decrease – and may possibly increase a bit to counteract the drop in blood glucose levels.[ref][ref]

Increases glucose uptake:

Blood glucose levels remain tightly regulated, and the release of insulin by the pancreas facilitates the uptake of glucose into cells. For most cells, glucose can’t cross the cell membrane without a transporter. The glucose transporters are known as GLUT1 through GLUT4, with different transporters in different cell types. The GLUT4 transporters are found in muscle tissue and fat cells. When blood glucose levels are high, the GLUT4 transporters are located in the cytosol of the cell (inside the cell), but when glucose levels fall, insulin levels rise. Insulin then binds to a receptor on the cell membrane, causing a cascade of actions that results in the GLUT4 transporters moving to the cell membrane. There, they can move glucose into the cells.

Metformin is thought to work in a way that keeps the GLUT4 transporters available on the cell surface so that the skeletal muscle cells can take up more glucose without needing more insulin.[ref]

Altered microbiome composition:

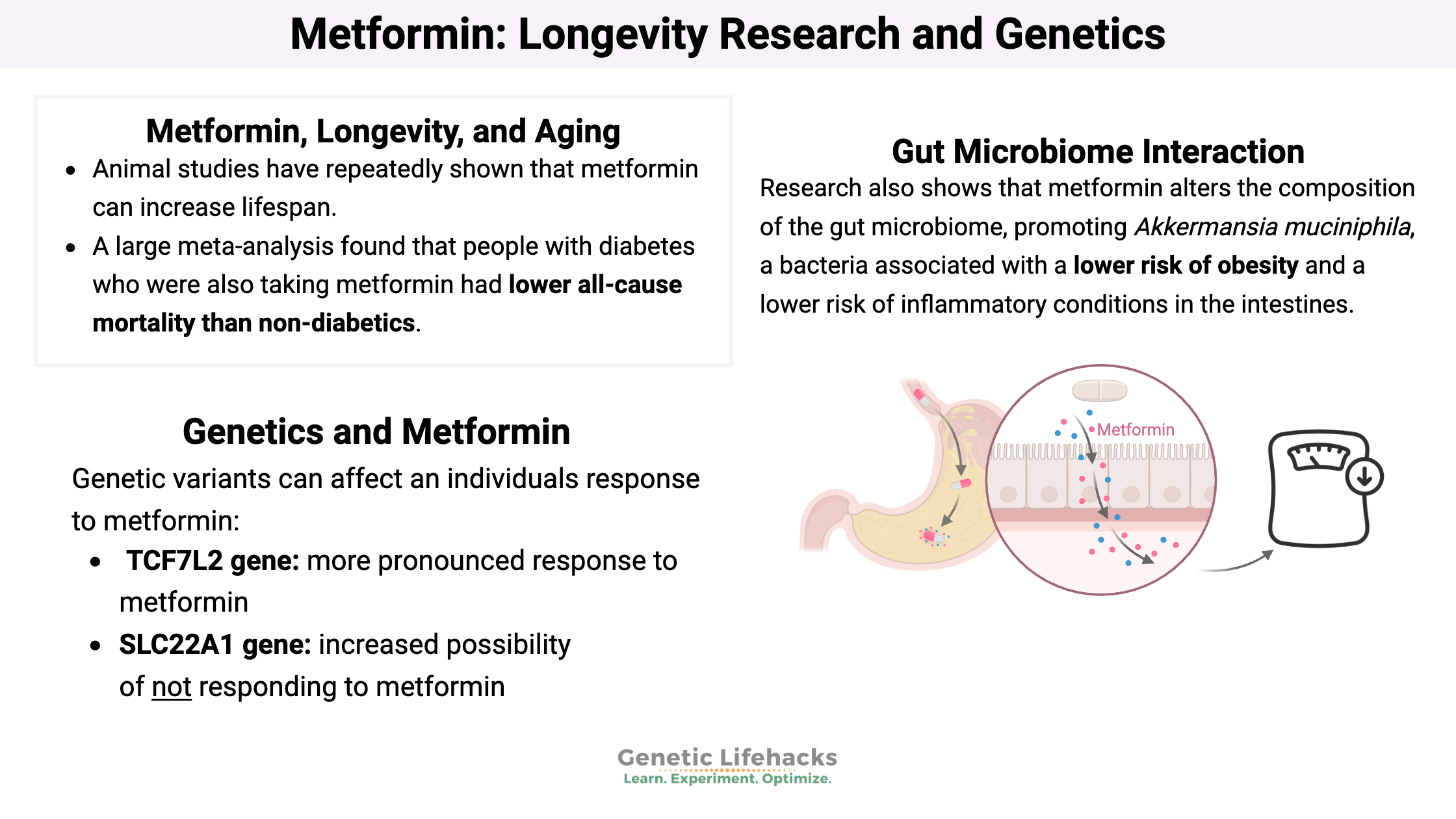

Research also shows that metformin alters the composition of the gut microbiome, promoting Akkermansia muciniphila, a bacteria associated with a lower risk of obesity and a lower risk of inflammatory conditions in the intestines. The altered gut microbiome composition may also be a mechanism through which metformin helps with diabetes. Additionally, metformin has been shown to increase short-chain fatty acid metabolism in the intestines.[ref][ref][ref]

PCOS and metformin:

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is characterized by insulin resistance and altered androgen hormone production. Studies show that metformin may be beneficial for women with PCOS. One study found that 12 weeks of metformin decreased testosterone levels and improved glucose effectiveness.[ref] Read more about PCOS and associated variants here.

Metformin for Longevity and Aging:

Many researchers are now looking at aging as a disease. In fact, the World Health Organization recently added it to its classification system as a disease. With this idea in mind, let’s take a look at the use of metformin to prevent chronic diseases in aging.

Animal studies have repeatedly shown that metformin can increase lifespan. Most of the studies show that starting metformin in middle age or earlier can increase lifespan and health span.[ref][ref][ref]

But humans aren’t the same as mice, and the results of animal studies sometimes don’t hold true for people.

Human studies on metformin show:

A large meta-analysis found that people with diabetes who were also taking metformin had lower all-cause mortality than non-diabetics. They also had lower cardiovascular disease and cancer rates. That is pretty amazing. The study also showed that diabetics taking metformin had lower rates of cancer than diabetics using other types of diabetes medications.[ref]

Another meta-analysis using data from over 1 million patients found that both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events were reduced significantly (20% for all-cause mortality and over 30% for cardiovascular events).[ref]

Other studies show that all-cause mortality and cancer-related mortality are reduced in people who take metformin.[ref]

Not all human studies show fantastic results:

In a study of heart attack patients, 4 months of metformin did not have beneficial long-term effects.[ref] Other studies show a possible impact that negates the benefits of aerobic exercise.[ref]

How can metformin extend healthspan?

One mechanism (other than decreased blood glucose levels) for a positive effect on healthy aging is that metformin may activate SIRT1. The Sirtuins are a family of enzymes that are important for regulating cellular homeostasis, and SIRT1 (sirtuin 1) is important in healthy aging. A link exists between the activation of SIRT1 and lower rates of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.[ref][ref]

Another mechanism through which metformin has been shown to act is in the way that mitochondria use fatty acids for energy. The ACAD10 gene codes for an enzyme needed in beta-oxidation and animal studies show that metformin acts through the inhibition of mTORC1 to upregulate ACAD10.[ref]

Impact on muscles:

A Dec 2019 randomized crossover trial shows that 4 days of metformin doesn’t impact skeletal muscle activity. Interestingly, the authors note that metformin caused the participants to feel like exercise took more exertion. Thus, it may cause people to want to exercise a little less.[ref]

In another study in older adults (age ~62), 3 months of metformin seemed to attenuate the benefits of aerobic exercise.[ref]

Potential negative side effects from metformin:

Most importantly, there is an increased risk of lactic acidosis in people taking metformin. This may be more of a risk for people with underlying kidney problems.[ref]

Some people have gastrointestinal side effects from metformin. People with SLC22A1 variants (below) are more likely to have gastrointestinal problems.[ref]

Metformin metabolism and excretion:

Metformin circulates unbound because its metabolism doesn’t occur in the liver. Instead, the kidneys clear it from the body facilitated by SLC22A2 kidney cells. (more on this below)[ref]

Metformin Response Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

If you are interested in metformin for longevity, talk with your doctor about whether getting a prescription for it is right for you.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

SIRTfoods diet: Sirtuins and turning on your skinny genes

A dive into the science of the fascinating SIRT genes, explaining how they work and showing you how to check your SIRT gene variants.

NAD+

Explore the research about how nicotinamide riboside (NR) and NMN are being used to reverse aging. Learn about how your genes naturally affect your NAD+ levels, and how this interacts with the aging process.

Telomeres

Your telomeres are the region at the end of each chromosome that keeps your DNA intact when your cells divide. Telomeres that get too short cause cells to stop dividing, leading to some of the diseases of aging.