Key takeaways:

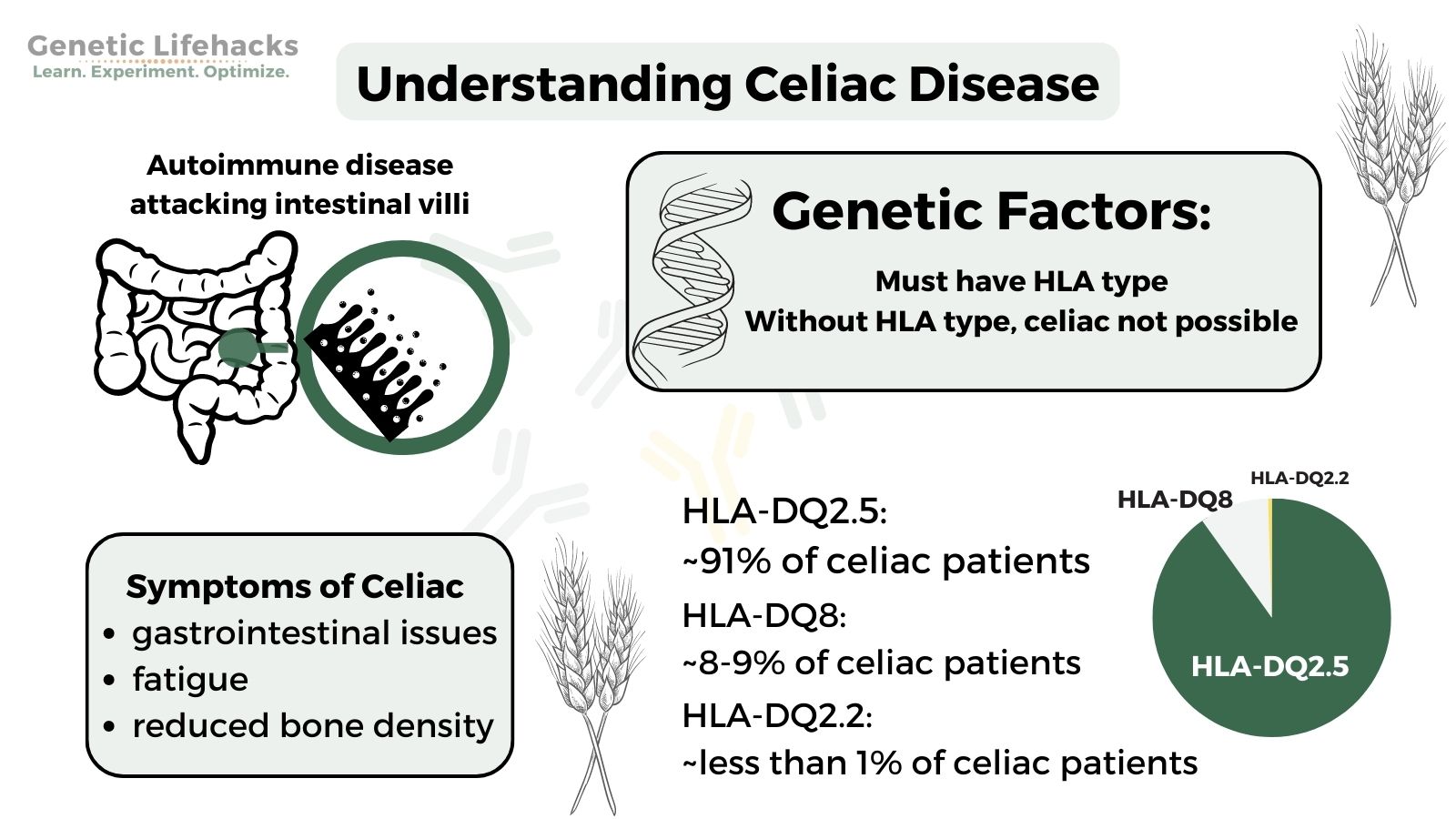

~ Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder in which gluten causes damage to the small intestines.

~ Celiac is only possible in people with specific HLA genotypes.

~ You can use your genetic raw data (23andMe, AncestryDNA, etc) to find out if you have the HLA type that makes you susceptible to celiac.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

What is celiac disease?

Celiac disease (spelled coeliac in Britain) is an autoimmune disorder in which gluten, a protein found in wheat and other grains, leads to your body attacking its own cells.

Inside the small intestines, there are little projections called villi. In celiac disease, the body attacks those cells, causing the villi to shorten and not absorb nutrients very well.

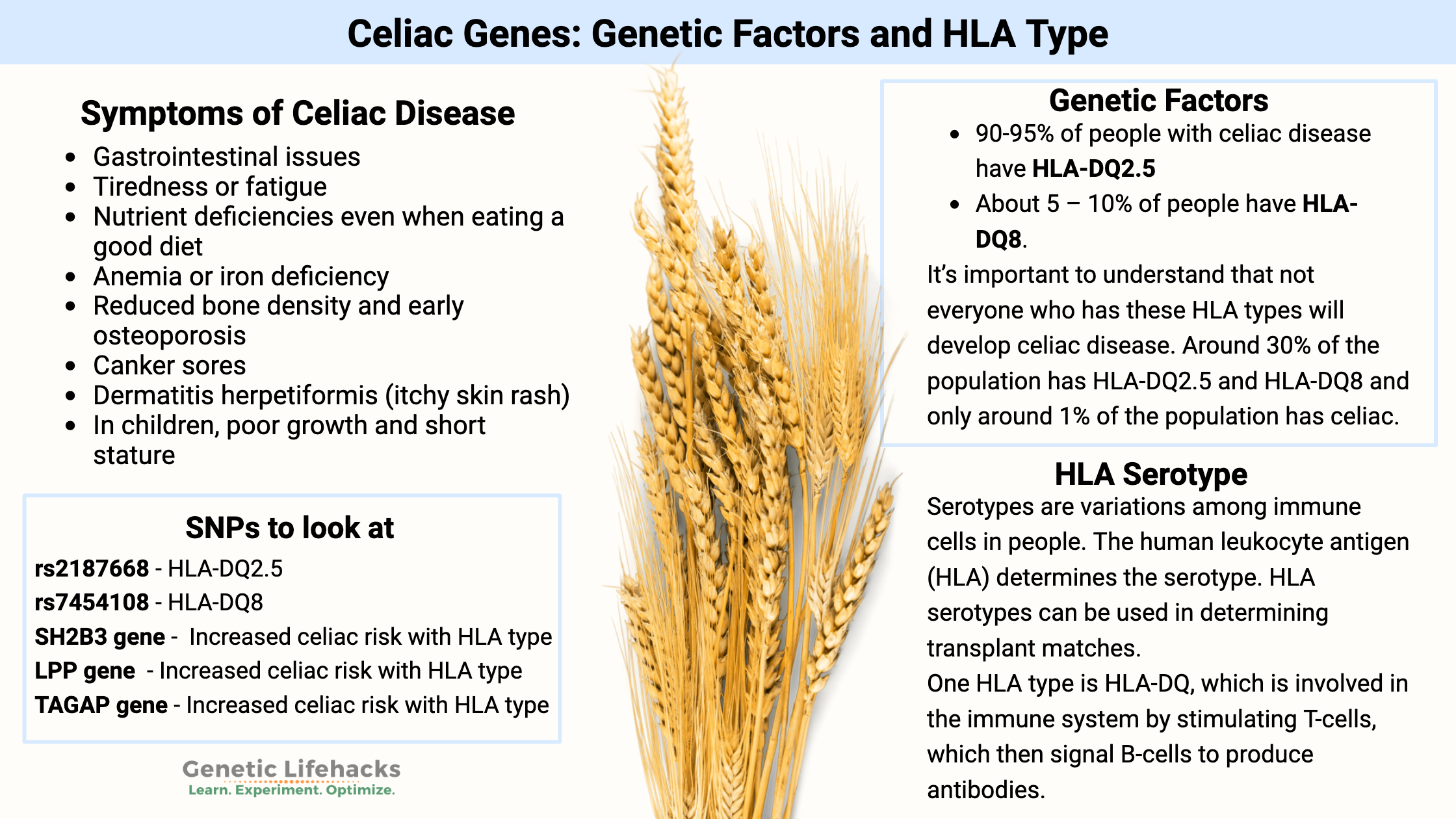

Symptoms of celiac disease:

Symptoms of celiac disease can vary from person to person, but some common ones include: [ref]

- Gastrointestinal issues

- Tiredness or fatigue

- Nutrient deficiencies even when eating a good diet

- Anemia or iron deficiency

- Reduced bone density and early osteoporosis

- Canker sores

- Dermatitis herpetiformis (itchy skin rash)

- In children, poor growth and short stature

It’s also worth noting that not everyone with celiac disease will have all of these symptoms.

Genetics and celiac:

In order for a person to be susceptible to celiac disease, certain genetic variants must be present. If these specific variants, called HLA alleles, are not present, it is highly unlikely that a person has celiac disease.

Almost everyone with Celiac disease has either the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 alleles.

- 90-95% of people with celiac disease have HLA-DQ2.5

- About 5 – 10% of people have HLA-DQ8.

- Some studies also list HLA-DQ2.2 as a possibility for celiac, with about 1% of celiac patients carrying HLA-DQ2.2.

It’s important to understand that not everyone who has these HLA types will develop celiac disease.

In fact, almost 25% of the population has HLA-DQ2.5, and that percentage grows to ~30% when adding in HLA-DQ8 alleles.[ref] With only ~1% of the population having celiac disease, you can see that just having the HLA type doesn’t mean that you will get celiac disease.

Genetics to rule it out:

Thus, looking at your genetic variants can help you rule out celiac disease, but it cannot tell you if you have it.

What is an HLA serotype?

Serotypes, discovered in 1933 by Rebecca Lancefield, are variations within species (bacteria and viruses) or variations among immune cells in people. The typing is based on their cell surface antigens. In humans, the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) determines the serotype. HLA serotypes can be used in determining transplant matches.

One HLA type is HLA-DQ, which is a protein found on antigen-presenting cells. DQ is involved in the immune system by stimulating T-cells, which then signal B-cells to produce antibodies.

HLA-DQ recognizes foreign antigens from pathogens, but it also recognizes common self-antigens. This is where the problem begins when the HLA-DQ loses its tolerance to self-proteins, triggering autoimmune diseases such as celiac, lupus, and type 1 diabetes.

Beyond the HLA types:

While the HLA-DQ types (DQ2.5, DQ8, and possibly DQ2.2) are necessary for celiac disease susceptibility, they are not sufficient on their own to cause celiac disease. Researchers have also found other genetic variants that add to HLA to increase the risk of celiac disease occurring. These variants are generally related to autoimmune risk and inflammatory response.[ref]

Gut microbiome:

In addition, the type of bacteria hosted in the intestines may play a role in celiac. This can be due to your genes (e.g. FUT2 non-secretor) or to early developmental influence on the gut microbiome. [ref] The HLA-DQ2 serotypes also influence the species and abundance of bacteria in the gut microbiome. A recent study found that several bacteria in the Firmicutes phylum are causally linked to celiac disease through the HLA-DQ2 serotypes.[ref]

Diagnosing Celiac Disease:

There are blood tests that can show whether you carry antibodies against gluten. The test is not 100% accurate, and some people may have false-negative results (e.g., a blood test shows that you don’t have celiac when you do).

Genetics can help you rule out celiac disease. If you don’t carry the HLA type (below) and also have a negative antibody test, then celiac is highly unlikely.

The ‘gold standard’ is an intestinal biopsy, where a gastroenterologist takes a small snip out of your intestines to see if there is damage to the villi.

Celiac Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

With celiac disease, a strict gluten-free diet is recommended as the treatment to prevent further damage to the intestines. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, triticale, and barley. It is also found as an ingredient in many processed foods, such as sauces, spice mixes, and soups. Barley is found in malt, beer, and some food coloring.[ref]

Testing for celiac disease:

After learning about the genetic variants linked with celiac disease, a lot of people immediately decide to try out a gluten-free diet. This can be a mistake!

For example, if you go on a gluten-free diet and feel great, you still don’t know if you have celiac disease or if you are just gluten intolerant.

For a person who has celiac disease, being 100% gluten-free is essential. This is an important difference from some people with gluten intolerance who may be able to handle small amounts of gluten.

Instead of jumping into a gluten-free diet, get tested first for celiac disease.

Your doctor is the place to start, and he/she can order testing for you. If your doctor won’t order the test – or you don’t have a doctor – you can order the blood tests yourself online (UltaLab Tests – Celiac is one option).

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Thyroid Hormones: Genes, Hypothyroidism, and T4/T3 Conversion

Graphical Abstract:

References:

Canova, Cristina, et al. “Celiac Disease and Risk of Autoimmune Disorders: A Population-Based Matched Birth Cohort Study.” The Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 174, July 2016, pp. 146-152.e1. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.058.

Huang, Shi-Qi, et al. “Association of LPP and TAGAP Polymorphisms with Celiac Disease Risk: A Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 14, no. 2, Feb. 2017, p. 171. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020171.

Hunt, Karen A., et al. “Newly Identified Genetic Risk Variants for Celiac Disease Related to the Immune Response.” Nature Genetics, vol. 40, no. 4, Apr. 2008, pp. 395–402. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.102.

Izzo, Valentina, et al. “Improving the Estimation of Celiac Disease Sibling Risk by Non-HLA Genes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 11, Nov. 2011, p. e26920. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026920.

—. “Improving the Estimation of Celiac Disease Sibling Risk by Non-HLA Genes.” PloS One, vol. 6, no. 11, 2011, p. e26920. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026920.

—. “Improving the Estimation of Celiac Disease Sibling Risk by Non-HLA Genes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 11, Nov. 2011, p. e26920. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026920.

—. “Improving the Estimation of Celiac Disease Sibling Risk by Non-HLA Genes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 11, Nov. 2011, p. e26920. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026920.

Leccioli, Valentina, et al. “A New Proposal for the Pathogenic Mechanism of Non-Coeliac/Non-Allergic Gluten/Wheat Sensitivity: Piecing Together the Puzzle of Recent Scientific Evidence.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 11, Nov. 2017, p. 1203. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111203.

Megiorni, Francesca, and Antonio Pizzuti. “HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 in Celiac Disease Predisposition: Practical Implications of the HLA Molecular Typing.” Journal of Biomedical Science, vol. 19, no. 1, Oct. 2012, p. 88. BioMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/1423-0127-19-88.

Monsuur, Alienke J., et al. “Effective Detection of Human Leukocyte Antigen Risk Alleles in Celiac Disease Using Tag Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms.” PLoS ONE, vol. 3, no. 5, May 2008, p. e2270. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002270.

Parmar, A. S., et al. “Association Study of FUT2 (Rs601338) with Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Finnish Population.” Tissue Antigens, vol. 80, no. 6, Dec. 2012, pp. 488–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/tan.12016.

“Symptoms of Celiac Disease.” Celiac Disease Foundation, https://celiac.org/about-celiac-disease/symptoms-of-celiac-disease/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2021.

Ting, Yi Tian, et al. “A Molecular Basis for the T Cell Response in HLA-DQ2.2 Mediated Celiac Disease.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 117, no. 6, Feb. 2020, pp. 3063–73. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914308117.

Trynka, Gosia, et al. “Dense Genotyping Identifies and Localizes Multiple Common and Rare Variant Association Signals in Celiac Disease.” Nature Genetics, vol. 43, no. 12, Nov. 2011, pp. 1193–201. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.998.

Tye-Din, J. A., et al. “Appropriate Clinical Use of Human Leukocyte Antigen Typing for Coeliac Disease: An Australasian Perspective.” Internal Medicine Journal, vol. 45, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. 441–50. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12716.

Yang, Guang, et al. “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between IL18RAP Rs917997 and CCR3 Rs6441961 Polymorphisms with Celiac Disease Risks.” Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 9, no. 10, 2015, pp. 1327–38. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1586/17474124.2015.1075880.