Key takeaways:

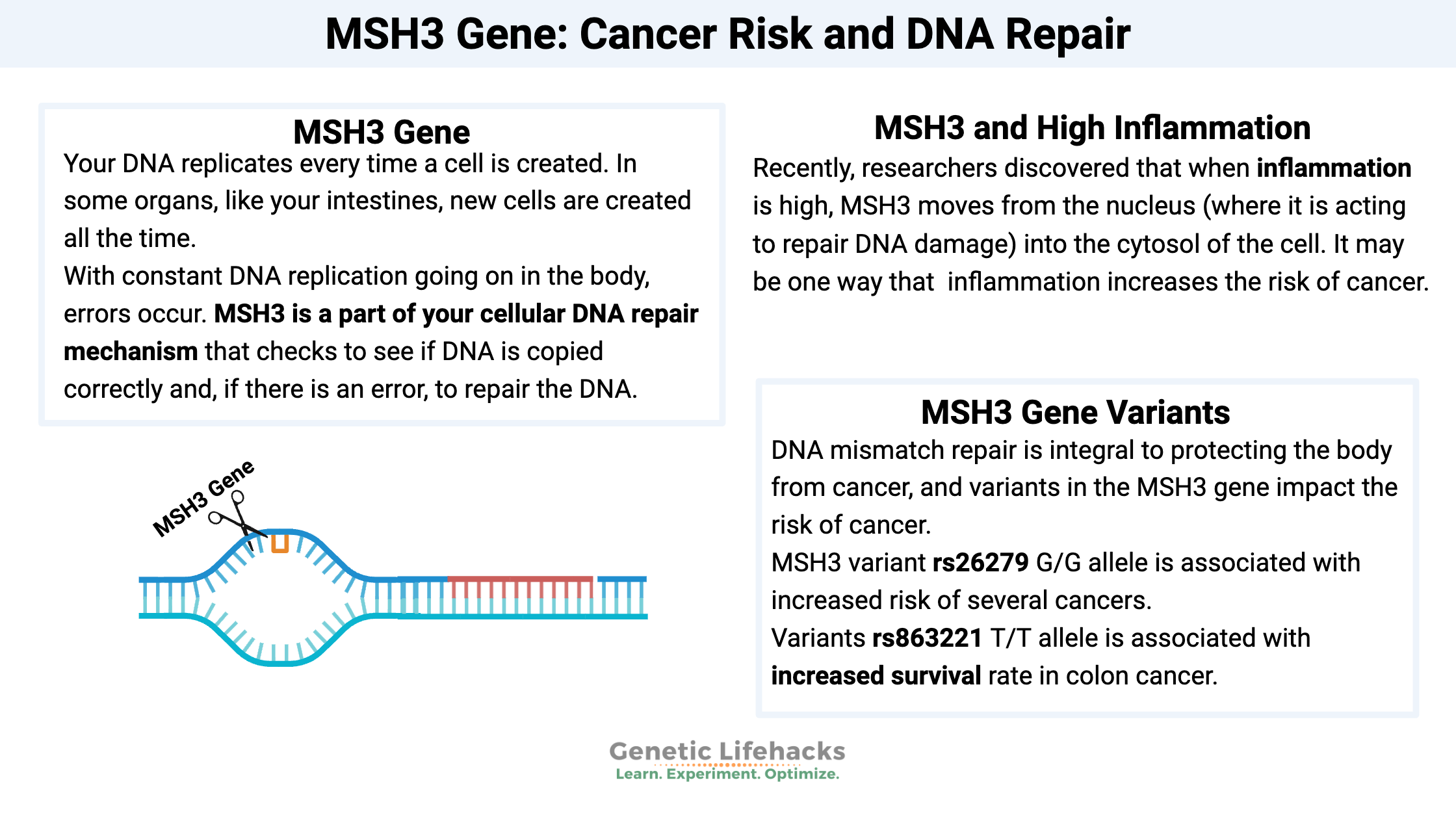

~ MSH3 is a DNA mismatch repair gene.

~ DNA mismatch repair is integral to protecting the body from cancer.

What does MSH3 do?

Your DNA replicates every time a cell is created. In some organs, like your intestines, new cells are created all the time. Cellular turnover is high, with the lifespan of intestinal epithelial cells being a short 3 to 5 days.[ref] In other organs, like the brain and heart, cells can stick around for a lifetime with limited cellular turnover.

With constant DNA replication going on in the body, errors occur. These errors in DNA replication are mutations in the DNA, which isn’t good. But cells have mechanisms in place to check that the DNA is copied correctly and, if there is an error, to repair the DNA.

MSH3 is part of this DNA repair mechanism.

MSH3 stands for MutS Homolog 3, which refers to its initial discovery as being similar to a bacterial mismatch repair protein.

Why is this important? In a word – cancer. DNA mismatch repair is integral to protecting the body from cancer. Mutations in growth-promoting genes (oncogenes) cause cancer, so the DNA mismatch repair process protects us from cancerous (and other) mutations.

Several different MSH proteins repair DNA mistakes. MSH3, specifically, acts to recognize the type of DNA replication mistakes that result in multiple nucleotides being messed up.[ref]

Additionally, MSH3 helps to repair double-stranded breaks. This is important in preventing cancer and because double-stranded breaks can sometimes cause cell death.[ref]

Recently, researchers discovered that when inflammation is high, MSH3 moves from the nucleus (where it is acting to repair DNA damage) into the cytosol of the cell. It may be one way that inflammation increases the risk of cancer.[ref]

MSH3 Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Learn more:

DNA replication and repair:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

References:

Asombang, Akwi W., et al. “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Esophageal Cancer in Africa: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Management and Outcomes.” World Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 25, no. 31, Aug. 2019, pp. 4512–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i31.4512.

Koessler, Thibaud, et al. “Common Germline Variation in Mismatch Repair Genes and Survival after a Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer.” International Journal of Cancer, vol. 124, no. 8, Apr. 2009, pp. 1887–91. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24120.

Liu, Jingwei, et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms of DNA Repair Pathways in Sporadic Colorectal Carcinogenesis.” Journal of Cancer, vol. 10, no. 6, 2019, pp. 1417–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.28406.

Miao, Hui-Kai, et al. “MSH3 Rs26279 Polymorphism Increases Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology, vol. 8, no. 9, 2015, pp. 11060–67.

Oers, Johanna M. M. van, et al. “The MutSβ Complex Is a Modulator of P53-Driven Tumorigenesis through Its Functions in Both DNA Double Strand Break Repair and Mismatch Repair.” Oncogene, vol. 33, no. 30, July 2014, p. 3939. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.365.

Park, Jung-Ha, et al. “Promotion of Intestinal Epithelial Cell Turnover by Commensal Bacteria: Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids.” PloS One, vol. 11, no. 5, 2016, p. e0156334. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156334.

Tseng-Rogenski, Stephanie S., et al. “The Human DNA Mismatch Repair Protein MSH3 Contains Nuclear Localization and Export Signals That Enable Nuclear-Cytosolic Shuttling in Response to Inflammation.” Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 40, no. 13, July 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00029-20.