Key takeaways:

~ The MTR and MTRR genes encode enzymes essential in the methylation cycle.

~ Genetic variations in the MTR and MTRR genes can alter enzyme activity, increasing risks for schizophrenia, cognitive impairment, and heart disease due to disrupted homocysteine and methionine levels.

~ Getting plenty of vitamin B12 and folate is important for people with MTR and MTRR variants.

This article explains where the MTR and MTRR genes fit within the methylation cycle. I’ll show you how to check your 23andMe or AncestryDNA raw data for the MTR and MTRR SNPs and then explain how to optimize your diet for these variants.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.MTR & MTRR Gene: Methionine and Vitamin B12

Methionine is an essential amino acid used in the production of proteins. It is literally the starting amino acid for every protein your body makes.

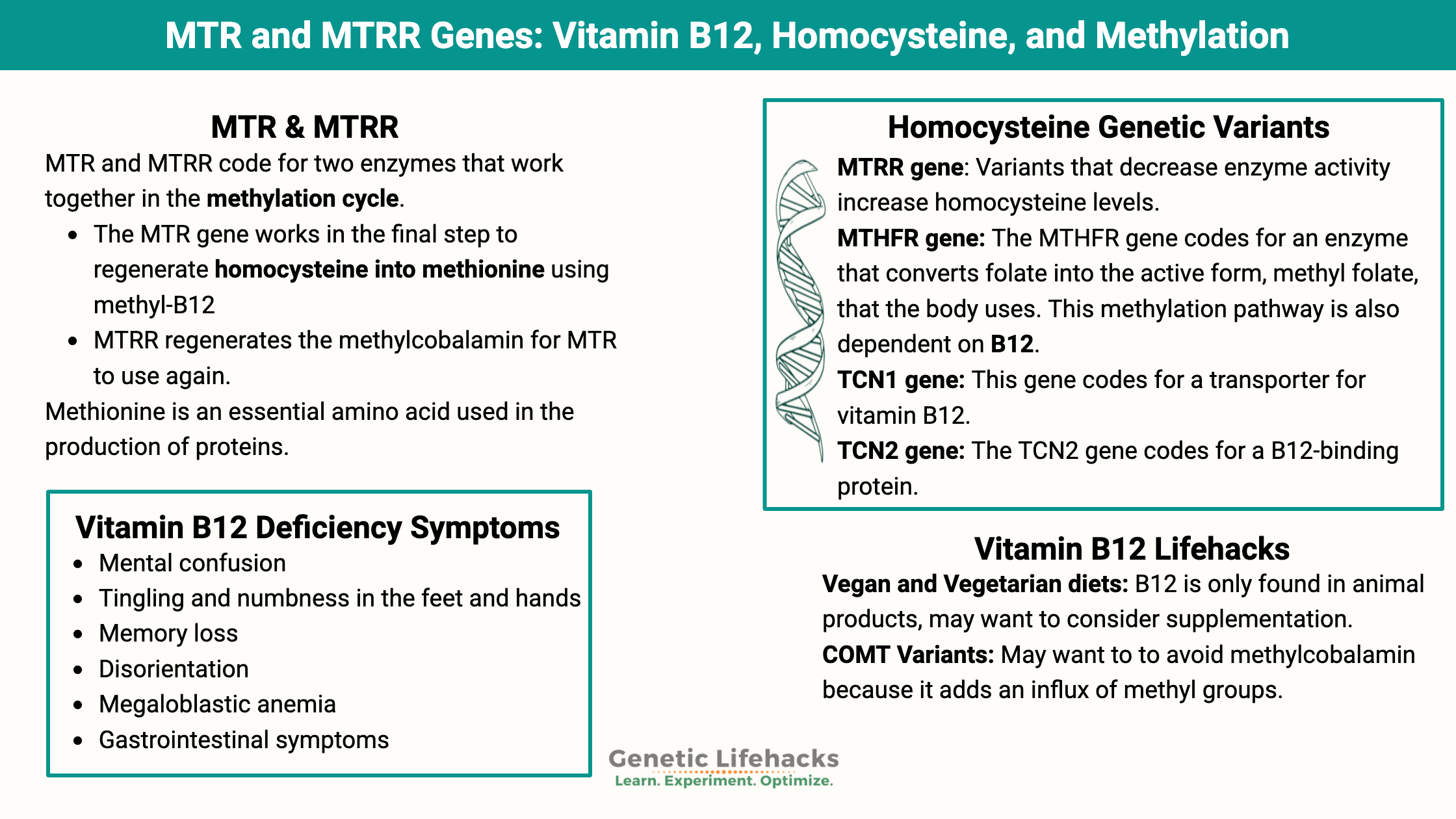

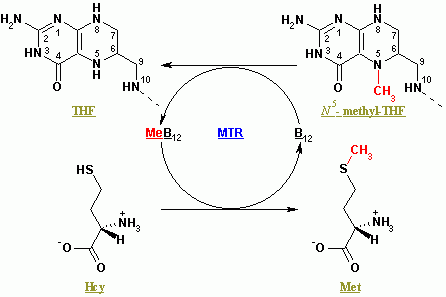

MTR (methionine synthase) and MTRR (methionine synthase reductase) code for two enzymes that work together in the methylation cycle.

- The MTR gene works in the final step to regenerate homocysteine into methionine using methyl-B12 (methylcobalamin)

- MTRR regenerates the methylcobalamin for MTR to use again.[ref]

Both are a vital part of the methylation cycle.

Methyl groups – in a nutshell:

Your body is made up of a bunch of organic molecules, a lot of which contain carbons bonded to hydrogen.

Adding in a methyl group (one carbon plus three hydrogens) is like adding a building block to the molecule.

The methylation cycle is your body’s way of recycling certain molecules to ensure that there are enough methyl groups (carbon plus three hydrogens) available for cellular processes. When it comes to the functioning of your cells, methyl groups are used in methylation reactions.[ref]

Examples of methylation reactions include:

- synthesis of some of the nucleic acid (DNA) bases

- turning off genes so that they aren’t transcribed (DNA methylation)

- converting serotonin into melatonin

- methylating arsenic so that it can be excreted

- breaking down neurotransmitters

- metabolizing estrogen

- regenerating methionine from homocysteine

Methylation in the right amount:

Goldilocks comes to mind here… You want to have the right amount of methylation reactions going on. Your cells work to keep this all in balance.

For example, you need enough folate (vitamin B9) and methylcobalamin (vitamin B12) for the methionine synthase reaction to occur. Methylfolate is the source of the methyl group that methionine synthase uses for converting homocysteine to methionine. (Read more about your MTHFR genes and methyl folate)

Not enough B12 or methyl folate?

MTR won’t convert as much homocysteine to methionine, leading to a buildup of homocysteine and limiting methionine. Too much homocysteine is strongly associated with increased risk of heart disease.[ref]

The other side of the picture, though, is that there may be times when limiting methionine is helpful, such as in fighting the proliferation of cancer cells.

Methotrexate, a chemotherapy drug, works by inhibiting the production of methyl folate, thus limiting methionine and DNA synthesis for cell growth.

MTR and MTRR Genotype Report:

Lifehacks: Optimizing B12 with Diet or the Right Supplement

Dietary Folate and B12:

A healthy diet high in folate and B12 seems to be essential for overcoming any deficits created by these two polymorphisms.

Foods high in folate include:

- leafy greens

- chicken liver

- beef liver

- asparagus

- broccoli

- legumes

Vegan and Vegetarian diets:

Vitamin B12 is only found in animal-based foods, so vegans and vegetarians are often deficient or marginal in their B12 status.[ref] B12 is often added to breakfast cereals and other refined products, so eating a vegetarian diet that includes packaged and refined foods may actually result in higher B12 levels (although probably not in better health…).

It takes several years to completely deplete your liver’s store of B12, so people who have recently started a vegan or vegetarian diet may still have moderate vitamin B12 levels.[ref]

Supplemental B12:

Related Articles and Topics:

Top 10 Genes to Check in Your Genetic Raw Data

These are 10 genes with important variants that can have a big impact on health. So check them out, cross them off your list if you don’t have them — and read the articles to learn more if you do carry the variant.

Folate & MTHFR

The MTHFR gene codes for a key enzyme in the folate cycle. MTHFR variants can decrease the conversion to methyl folate.

CBS variants and low sulfur

This article digs into the high-quality research on the common CBS genetic variants to determine if there is any evidence suggesting everyone should be on a low-sulfur diet. Read through the research and check your genetic data.

References:

Ankar, Alex, and Anil Kumar. “Vitamin B12 Deficiency.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2022. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/.

Deng, Changfei, et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms in MTR Are Associated with Non-Syndromic Congenital Heart Disease from a Family-Based Case-Control Study in the Chinese Population.” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, Mar. 2019, p. 5065. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41641-z.

Ducker, Gregory S., and Joshua D. Rabinowitz. “One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease.” Cell Metabolism, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 27–42. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.009.

Gallego-Narbón, Angélica, et al. “Vitamin B12 and Folate Status in Spanish Lacto-Ovo Vegetarians and Vegans.” Journal of Nutritional Science, vol. 8, Feb. 2019, p. e7. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2019.2.

Homocysteine Studies Collaboration. “Homocysteine and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease and Stroke: A Meta-Analysis.” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 16, Oct. 2002, pp. 2015–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.16.2015.

Luo, Mei, et al. “Correlation of Homocysteine Metabolic Enzymes Gene Polymorphism and Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Xinjiang Uygur Population.” Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, vol. 21, Jan. 2015, pp. 326–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.893226.

“Methionine Synthase.” Wikipedia, 30 Sept. 2022. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Methionine_synthase&oldid=1113220848.

Pardini, Barbara, et al. “MTHFR and MTRR Genotype and Haplotype Analysis and Colorectal Cancer Susceptibility in a Case-Control Study from the Czech Republic.” Mutation Research, vol. 721, no. 1, Mar. 2011, pp. 74–80. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.12.008.

Raffield, Laura M., et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Homocysteine in African Americans from the Jackson Heart Study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, and the Coronary Artery Risk in Young Adults Study.” Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 63, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 327–37. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-017-0384-9.

Roffman, Joshua L., et al. “Genetic Variation Throughout the Folate Metabolic Pathway Influences Negative Symptom Severity in Schizophrenia.” Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 39, no. 2, Mar. 2013, pp. 330–38. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr150.

Sangrajrang, Suleeporn, et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms in Folate and Alcohol Metabolism and Breast Cancer Risk: A Case-Control Study in Thai Women.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, vol. 123, no. 3, Oct. 2010, pp. 885–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-0804-4.

Wang, Ping, et al. “Association of MTRR A66G Polymorphism with Cancer Susceptibility: Evidence from 85 Studies.” Journal of Cancer, vol. 8, no. 2, 2017, pp. 266–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.17379.

Weiner, Alexandra S., et al. “Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase C677T and Methionine Synthase A2756G Polymorphisms Influence on Leukocyte Genomic DNA Methylation Level.” Gene, vol. 533, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 168–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.098.

Xu, Weihai, et al. “Association between Methionine Synthase Reductase A66G Polymorphism and Male Infertility: A Meta-Analysis.” Critical Reviews in Eukaryotic Gene Expression, vol. 27, no. 1, 2017, pp. 37–46. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2017018680.