Key takeaways:

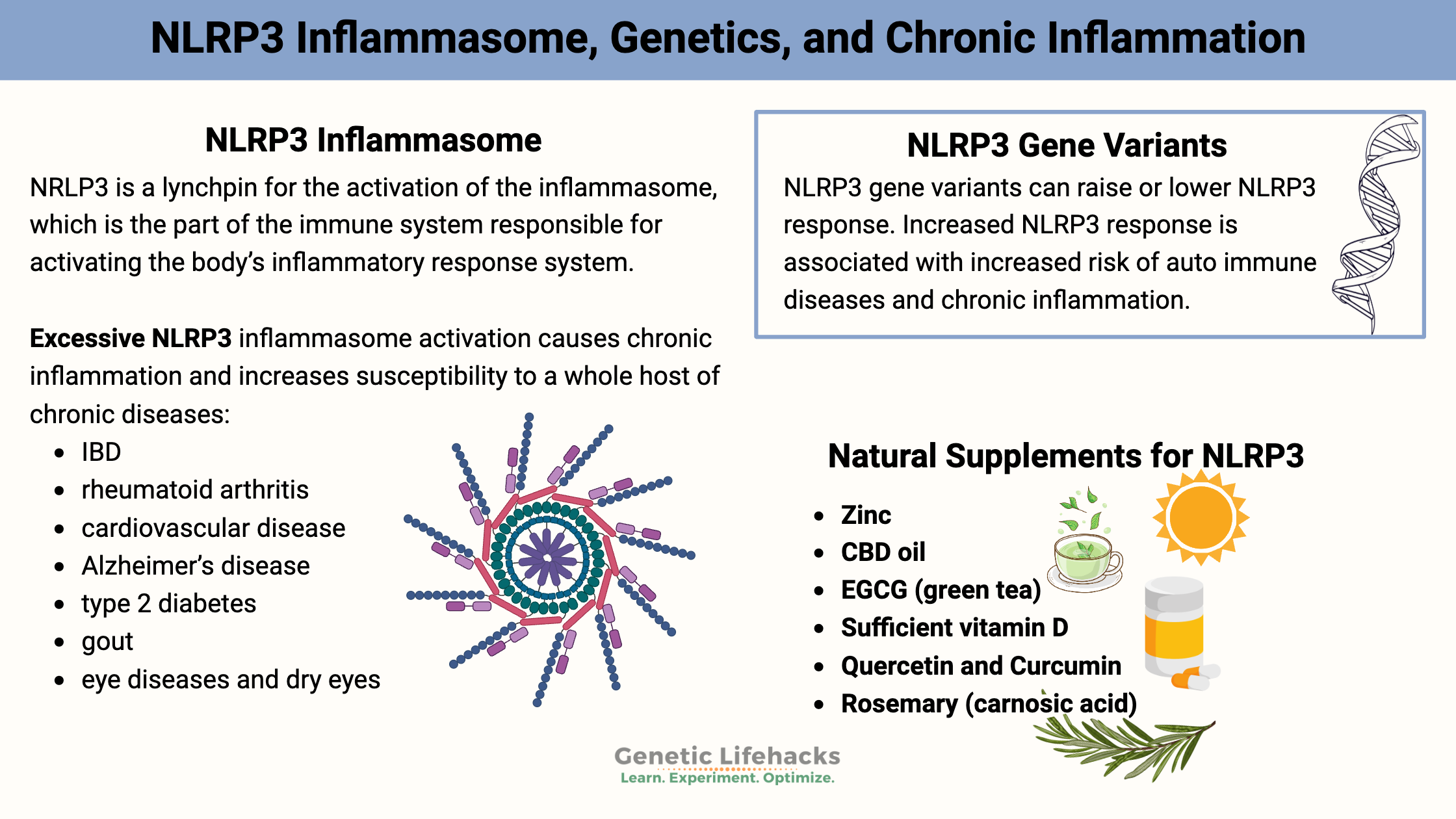

~ The NLRP3 inflammasome senses pathogens and cell damage and then increases and amplifies the inflammatory response.

~ Overactivation of NLRP3 is linked to chronic diseases like gout, Alzheimer’s, and type 2 diabetes.

~ Genetic variants in NLRP3 can cause the over-activation of inflammation in conjunction with diet and lifestyle, in turn causing chronic diseases.

~ Diet and nutrients like zinc and vitamin D may help regulate NLRP3 activity. Supplements such as resveratrol, curcumin, urolithin A, and more can also regulate NLRP3.

~ Understanding your NLRP3 genetics can guide personalized strategies to reduce chronic inflammation.

What is NLRP3, and how is the inflammatory response system activated?

NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor, pyrin domain-containing 3 ) is a lynchpin for the activation of the inflammasome, which is the part of the immune system responsible for activating the body’s inflammatory response system.

Essentially, NLRP3 is a danger-sensing protein.

Inflammasomes are immune complexes that amplify the immune system response. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by:[ref]

- Pathogens (e.g., bacterial or viral infection)

- DNA replication errors in a cell (e.g., mutation that could cause cancer)

- Cellular damage, such as lysosomes breaking open, and mitochondrial dysfunction

The inflammasome calls up the troops, amplifying the immune system response so that it is more powerful and able to overwhelm the pathogens.

~ Balance is key with NLRP3~

Excessive, persistent NLRP3 inflammasome activation causes chronic inflammation and increases susceptibility to a whole host of chronic diseases:[ref][ref]

| Conditions associated with NLRP3 activation | |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s, UC) Rheumatoid arthritis Cardiovascular disease Atrial fibrillation Alzheimer’s disease |

Type 2 diabetes Gout Eye diseases and dry eyes Osteoarthritis Cancer |

What activates NLRP3?

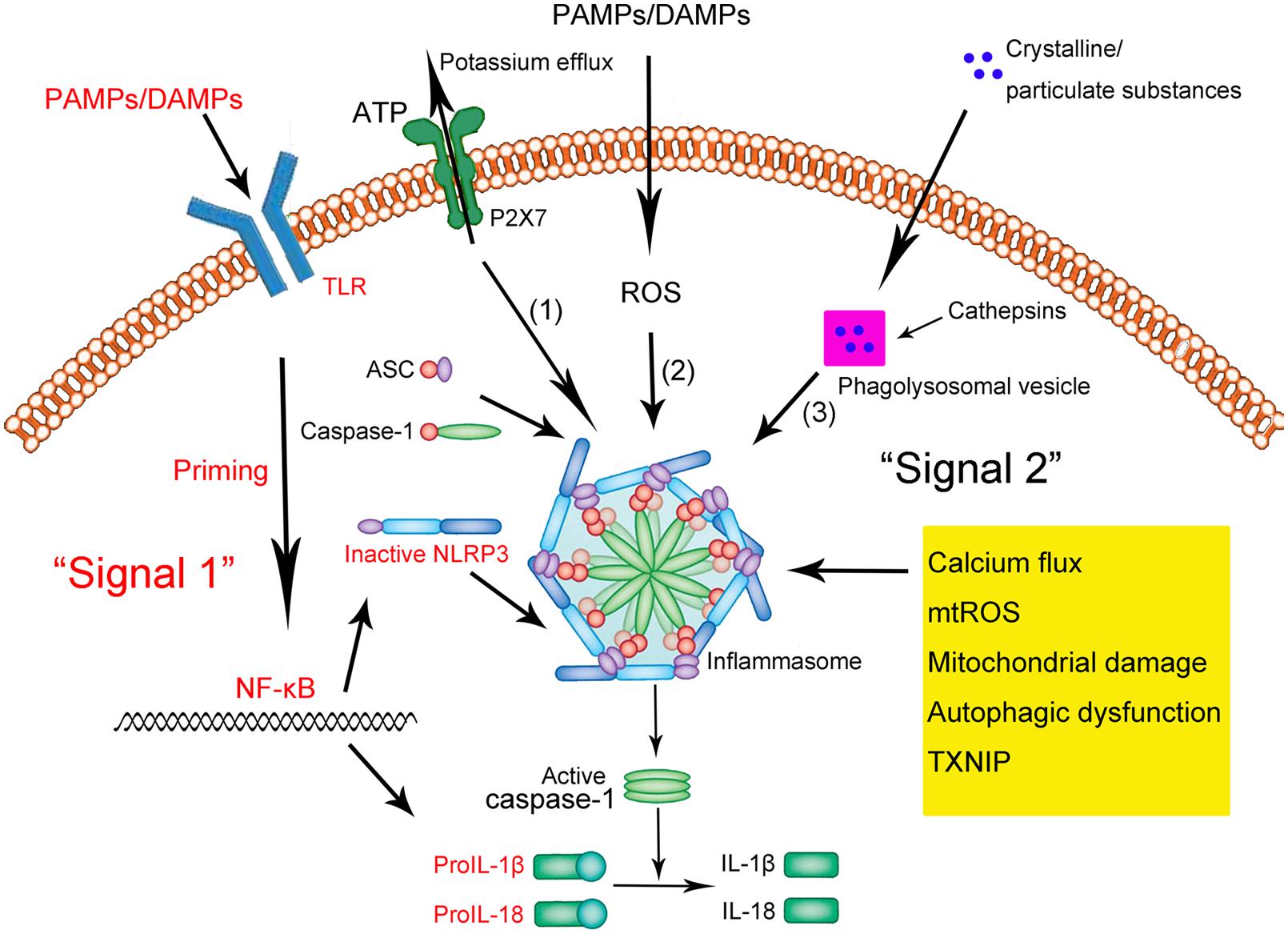

NLRP3 hangs out in the cytosol of immune cells in an inactive form. It is mainly found in macrophages and a few other types of immune cells.[ref] When activated, NLRP3 binds together to form a big complex with another protein called ASC to form the inflammasome complex.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is triggered by:[ref]

- Damage-associated factors in the body

- uric acid crystals

- amyloid-beta plaque (found in Alzheimer’s brains)

- tau tangles (found in Alzheimer’s brains)

- extracellular ATP (indicates cell damage)

- ROS (reactive oxygen species)

- Specific viruses (e.g., adenovirus, influenza, Sendai virus, coronaviruses, Covid)

- Specific fungi (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans)

- Bacterial RNA (e.g., Listeria, E. coli, M. tuberculosis, and Staphylococcus aureus)[ref]

- Certain parasites (e.g., Trichomonas vaginalis)[ref]

- Asbestos and Silica particles[ref], Heavy metals

- Microplastic and nanoplastic particles[ref]

NLRP3 primes for an inflammatory response:

When a pathogen or danger-associated factor triggers a receptor, such as a toll-like receptor or TNF receptor, it causes an increase in the production of NLRP3. This ‘primes’ a cell to be ready for the pathogen or damage-associated factor. When the primed cell then comes in contact with the pathogen/damage signal, a series of reactions take place with NLRP3 clustering together with ASC, resulting in the activation of caspase-1.

Let’s look at what happens when NLRP3 is activated in more detail:

What happens when the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated?

When activated by a pathogen (e.g., gram-negative bacteria) or a cellular danger signal (e.g., ROS, ATP efflux, calcium flux), the NLRP3 inflammasome increases the secretion of pro-IL1β and IL-18. These are precursors to the inflammatory cytokines.

NLRP3 activation causes Caspase-1 to be activated. Caspase-1 acts as an enzyme to turn on the active version IL-1B, a strong inflammatory cytokine. Another inflammatory cytokine, IL-18 is also activated by caspase-1 via NLRP3.

These two powerful pro-inflammatory cytokines then cause pyroptosis, an inflammatory form of cell death.[ref][ref]

This inflammatory cell death, pyroptosis, is a hard-core response to fight off pathogens inside a cell, such as certain bacteria and viruses. The abrupt cell death stops the microbes from replicating and allows the immune system to take care of them.

In cancer, NLRP3 is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, NLRP3 activation is important in destroying potential cancer cells by targeting DNA-damaged cells for pyroptosis. However, chronic NLRP3 activation can lead to inflammatory or autoimmune conditions that are more likely to cause cancer.[ref][ref]

With such a powerful response, activation of NLRP3 when it is not needed can cause a lot of chronic problems in the body.

Over-activation of NLRP3:

Again, balance is key in NLRP3 activation.

| Disease/Condition | Mechanism/Trigger | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gout | Monosodium urate crystals | Direct NLRP3 activation |

| Atherosclerosis | Oxidized cardiolipin | Chronic inflammatory response |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | Over-activation of microglia | NLRP3 inflammasome involvement |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid-beta deposits | NLRP3 activation, IL-1B increase |

| Type 2 diabetes | Mitochondrial ROS | Chronic low-grade inflammation |

| Rare autoinflammatory syndromes | Genetic NLRP3 mutations | CAPS, Muckle-Wells, familial cold syndrome |

Chronic diseases associated with NLRP3 over-activation and/or NLRP3 genetic variants:

- Gout is caused by monosodium urate crystals in the joint triggering inflammation. Monosodium urate is one trigger of NLRP3 activation of the inflammasome, and genetic variants in NLRP3 are associated with an increased risk of gout.[ref][ref] (Learn more about genetic links to high uric acid.)

- Atherosclerosis, the build-up of plaque in the arteries, also involves NLRP3 activation and a chronic inflammatory response.[ref] Cardiolipin is a phospholipid that is part of the mitochondrial membrane. In atherosclerotic plaques, oxidized cardiolipin accumulates. Cardiolipin is one trigger of NLRP3 activation when it moves from the inner mitochondrial membrane to the outer membrane in mitochondrial dysfunction.[ref][ref][ref]

- Autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS). The over-activation of microglia and the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome are big parts of the problem in MS.[ref][ref]

- Alzheimer’s disease has links to amyloid-beta deposits in the brain. These amyloid-beta deposits activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, increasing IL-1β B in the brain.[ref] NLRP3 activation may be part (all?) of the cause of the tau tangles. Animal research is still ongoing here.[ref] (Learn about APOE and Alzheimer’s risk.)

- Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance have links to chronic low-grade inflammation due to NLRP3 activation. NLRP3 proteins, IL-1β, and IL-18 are upregulated in people with type 2 diabetes. One cause of this is mitochondrial ROS (reactive oxygen species).[ref][ref]

Rare mutations that cause a gain-of-function in NLRP3 can cause genetic autoinflammatory conditions. While uncommon, understanding these conditions gives us a picture of what overactivation of NLRP3 can lead to.

Rare auto-inflammatory diseases caused by NLRP3 mutations include:

- Cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome (CAPS) is a rare autoinflammatory syndrome that can be caused by mutations in NLRP3. Symptoms include fever, itchy rash, conjunctivitis, headaches, hearing loss, and joint pain.[ref] CAPS is caused by the NLRP3 inflammasome being overly sensitive to being primed and always active.[ref]

- Muckle-Wells syndrome is an auto-inflammatory syndrome caused by rare mutations in the NLRP3 gene. Researchers now consider this a type of CAPS.[ref] Symptoms include episodes of fever, chills, and painful joints. It is often exacerbated by cold. Additional symptoms of Muckle-Wells syndrome include recurrent conjunctivitis (pink eye), progressive hearing loss (later in life), and possibly amyloidosis.[ref]

- Familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome is another milder subset of CAPS.[ref] Also caused by rare mutations in the NLRP3 gene, familial cold auto-inflammatory (or urticaria) syndrome is triggered by exposure to cold. Symptoms include fever, joint pain, and an itchy rash.[ref]

Repetitive behaviors (stimming):

A 2025 study involving mice with an NLRP3 gain-of-function mutation similar to the one found in people with autoinflammatory syndromes showed an interesting connection to repetitive behaviors. The researchers stimulated the NLRP3 inflammasome with lipopolysaccharide (a component of bacteria that triggers inflammation). The researchers found that activating the NLRP3 inflammasome “induced anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors frequently found in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders”. It also increased NMDA receptor functions and increased glutamatergic (excitatory) signaling in the brain. Importantly, blocking NLRP3 activation completely reversed the repetitive behavior symptoms.[ref]

Covid and NLRP3:

The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus can cause COVID-19. Severe cases of COVID-19 have a strong inflammatory response going on in the body, causing damage that can lead to organ damage or death. Recent research shows the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in COVID-19 and may contribute to severity and mortality.[ref][ref]

MicroRNAs and NLRP3 gene expression: ME/CFS connection

ME/CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome) is characterized by physiological changes that cause extreme fatigue and an inability to handle mental or physical exertion. Animal studies have shown that NLRP3 inflammasome activation is part of what causes the normal feelings of fatigue after exertion.[ref]

MicroRNAs are short strands of RNA that can prevent a gene from being translated into its protein. MiR-22 directly targets NLRP3 and keeps it from being expressed.[ref] Interestingly, miR-22 is decreased in the cerebrospinal fluid of ME/CFS and Gulf War Illness patients post-exercise.[ref][ref]

Genetic variants that impact NLRP3 activation:

Variants that increase the function of the NLRP3 gene are linked to many different chronic diseases that are caused by excess inflammation.

Overactivation of NLRP3 can also cause someone to have a more severe reaction to a viral or bacterial illness. For example, the rs35829419 A allele increases NLRP3 activation in response to acute infection. People with the variant had a 13-fold increased risk of having ‘Fatigue’, ‘Musculoskeletal pain’, ‘Mood disturbance’, and ‘Acute sickness’ while sick with Epstein-Barr virus (e.g. mono), Q fever, or a mosquito-born infection.[ref]

Variants that increase NLRP3 activation can also be a problem in transplant recipients. For example, a study showed that variants increasing NLRP3 are associated with acute rejection of kidney transplantation, while a loss-of-function NLRP3 mutation decreased the risk of rejection.[ref]

Tradeoffs: Keep in mind that a strong inflammatory response may be of benefit in fighting off certain infectious diseases. It is likely that the NLRP3 variants are found in the human population because they gave our ancestors an advantage in surviving a pathogen. It’s a balance, though, with too much of an inflammatory response to a pathogen being detrimental, especially in the elderly.

NLRP3 Genotype Report

Lifehacks:

If you have genetic variants that increase NLRP3 activation, consider whether tamping down the overactivation would be helpful for you. In general, you don’t want an overactive immune response, but if you are on immunosuppressant drugs, it may not be a good idea to further suppress NLRP3 activation. As always, check with your doctor or make sure that a supplement or diet change is right for you before implementing any of these ‘lifehacks’.

Dietary considerations for decreasing NLRP3 activation:

| Diet/Nutrient | Mechanism/Effect on NLRP3 | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Reduces NLRP3 activation | Increase dietary zinc, supplement if deficient |

| Vitamin D | Modulates NLRP3 activation | Vitamin D receptor regulates NLRP3 |

| Mediterranean diet | Improves insulin sensitivity in non-diabetics | Specific to NLRP3 variant carriers |

Get enough zinc:

A recent animal study showed that zinc deficiency accelerated memory loss in a model of Alzheimer’s disease via increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation.[ref] Foods that are high in zinc include oysters, beef, crab, lobster, chicken, pork, and pumpkin seeds.[ref] Zinc supplements are also available if you don’t get enough via your diet.

Related article: Genetic variants impact your need for zinc

Sufficient vitamin D levels:

Vitamin D is important in modulating the body’s inflammatory response. The vitamin D receptor is a regulator of NLRP3 activation.[ref][ref] Animal studies show that vitamin D3 is important in inhibiting excessive NLRP3 activation.[ref][ref]

Related article: Vitamin D genetic variants in the immune response

Healthy diet:

NLRP3 activation plays a role in insulin resistance. The Mediterranean diet increased insulin sensitivity in non-diabetic NLRP3 variant carriers. Unfortunately, no benefit was seen for diabetic patients.[ref]

Natural supplements that decrease inflammation via NLRP3:

Related Articles and Topics:

TNF-alpha: Inflammation and Your Genes

Do you feel like you are always dealing with inflammation? Joint pain, food sensitivity, etc? Perhaps you are genetically geared towards a higher inflammatory response. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is an inflammatory cytokine that acts as a signaling molecule in our immune system.

Immune System and Inflammation Topic Summary Report

The Topic Summary Reports are a handy way to see which articles may be most relevant to you. These summaries are attempting to distill the complex information down into just a few words. Please see the linked articles for details and complete references. (Member’s article)

Chronic Inflammation & Autoimmune Risk – IL17

Inflammation can be blamed for everything from heart disease to mood disorders to obesity. Yet, how does this somewhat nebulous idea of too much inflammation tie into our genes? It seems that some people have a more sensitive immune system and are more prone to inflammatory reactions. (Member’s article)

Mast cells: MCAS, genetics, and solutions

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, or MCAS, is a recently recognized disease involving mast cells that are misbehaving in various ways. Symptoms of MCAS can include abdominal pain, nausea, itching, flushing, hives, headaches, heart palpitations, anxiety, brain fog, and anaphylaxis.

References:

Ahn, Huijeong, et al. “Methylene Blue Inhibits NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2, and Non-Canonical Inflammasome Activation.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, Sept. 2017, p. 12409. PubMed Central, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12635-6.

Day, T. G., et al. “Autoinflammatory Genes and Susceptibility to Psoriatic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis.” Arthritis and Rheumatism, vol. 58, no. 7, July 2008, pp. 2142–46. PubMed, doi:10.1002/art.23604.

Dostert, Catherine, et al. “Innate Immune Activation through Nalp3 Inflammasome Sensing of Asbestos and Silica.” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 320, no. 5876, May 2008, pp. 674–77. PubMed, doi:10.1126/science.1156995.

Estfanous, Shady Z. K., et al. “Inflammasome Genes’ Polymorphisms in Egyptian Chronic Hepatitis C Patients: Influence on Vulnerability to Infection and Response to Treatment.” Mediators of Inflammation, vol. 2019, 2019, p. 3273645. PubMed, doi:10.1155/2019/3273645.

Gu, Na-Yeong, et al. “Trichomonas Vaginalis Induces IL-1β Production in a Human Prostate Epithelial Cell Line by Activating the NLRP3 Inflammasome via Reactive Oxygen Species and Potassium Ion Efflux.” The Prostate, vol. 76, no. 10, July 2016, pp. 885–96. PubMed, doi:10.1002/pros.23178.

Hanaei, S., et al. “Association of NLRP3 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Ulcerative Colitis: A Case-Control Study.” Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology, vol. 42, no. 3, June 2018, pp. 269–75. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.clinre.2017.09.003.

Heneka, Michael T., et al. “NLRP3 Is Activated in Alzheimer´s Disease and Contributes to Pathology in APP/PS1 Mice.” Nature, vol. 493, no. 7434, Jan. 2013, pp. 674–78. PubMed Central, doi:10.1038/nature11729.

Herman, Rok, et al. “Genetic Variability in Antioxidative and Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Risk for PCOS and Influences Metabolic Profile of the Syndrome.” Metabolites, vol. 10, no. 11, Oct. 2020, p. 439. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/metabo10110439.

Imani, Danyal, et al. “Association of Nod-like Receptor Protein-3 Single Nucleotide Gene Polymorphisms and Expression with the Susceptibility to Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis.” International Journal of Immunogenetics, vol. 45, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 329–36. PubMed, doi:10.1111/iji.12401.

—. “Association of Nod-like Receptor Protein-3 Single Nucleotide Gene Polymorphisms and Expression with the Susceptibility to Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis.” International Journal of Immunogenetics, vol. 45, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 329–36. PubMed, doi:10.1111/iji.12401.

Ising, Christina, et al. “NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Drives Tau Pathology.” Nature, vol. 575, no. 7784, Nov. 2019, pp. 669–73. PubMed Central, doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1769-z.

Iyer, Shankar S., et al. “Mitochondrial Cardiolipin Is Required for Nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation.” Immunity, vol. 39, no. 2, Aug. 2013, pp. 311–23. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.001.

Jenko, Barbara, et al. “NLRP3 and CARD8 Polymorphisms Influence Higher Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis.” Journal of Medical Biochemistry, vol. 35, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 319–23. PubMed, doi:10.1515/jomb-2016-0008.

Keddie, Stephen, et al. “Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Fever Syndrome and the Nervous System.” Current Treatment Options in Neurology, vol. 20, no. 10, Sept. 2018, p. 43. PubMed, doi:10.1007/s11940-018-0526-1.

Lee, Hye Eun, et al. “Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Prevents Acute Gout by Suppressing NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Mitochondrial DNA Synthesis.” Molecules, vol. 24, no. 11, June 2019, p. 2138. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/molecules24112138.

—. “Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Prevents Acute Gout by Suppressing NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Mitochondrial DNA Synthesis.” Molecules, vol. 24, no. 11, June 2019, p. 2138. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/molecules24112138.

Lee, Hye-Mi, et al. “Upregulated NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes.” Diabetes, vol. 62, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 194–204. PubMed Central, doi:10.2337/db12-0420.

Lin, Zhi-Hang, et al. “Methylene Blue Mitigates Acute Neuroinflammation after Spinal Cord Injury through Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Microglia.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, vol. 11, Dec. 2017, p. 391. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fncel.2017.00391.

Malhotra, Sunny, et al. “NLRP3 Inflammasome as Prognostic Factor and Therapeutic Target in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Patients.” Brain: A Journal of Neurology, vol. 143, no. 5, May 2020, pp. 1414–30. PubMed, doi:10.1093/brain/awaa084.

Meyers, Allison K., and Xuewei Zhu. “The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Metabolic Regulation and Contribution to Inflammaging.” Cells, vol. 9, no. 8, July 2020, p. 1808. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/cells9081808.

—. “The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Metabolic Regulation and Contribution to Inflammaging.” Cells, vol. 9, no. 8, July 2020, p. 1808. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/cells9081808.

Moossavi, Maryam, et al. “Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Cancer.” Molecular Cancer, vol. 17, Nov. 2018, p. 158. PubMed Central, doi:10.1186/s12943-018-0900-3.

—. “Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Cancer.” Molecular Cancer, vol. 17, Nov. 2018, p. 158. PubMed Central, doi:10.1186/s12943-018-0900-3.

Office of Dietary Supplements – Zinc. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Zinc-HealthProfessional/. Accessed 15 July 2021.

Olcum, Melis, et al. “Microglial NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Multiple Sclerosis.” Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology, vol. 119, 2020, pp. 247–308. PubMed, doi:10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.08.007.

Paramel Varghese, Geena, et al. “NLRP3 Inflammasome Expression and Activation in Human Atherosclerosis.” Journal of the American Heart Association, vol. 5, no. 5, May 2016, p. e003031. PubMed, doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.003031.

Rheinheimer, Jakeline, et al. “Current Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome on Obesity and Insulin Resistance: A Systematic Review.” Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, vol. 74, Sept. 2017, pp. 1–9. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2017.06.002.

Rivers-Auty, Jack, et al. “Zinc Status Alters Alzheimer’s Disease Progression through NLRP3-Dependent Inflammation.” Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 41, no. 13, Mar. 2021, pp. 3025–38.

Rodrigues, Tamara S., et al. “Inflammasomes Are Activated in Response to SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Are Associated with COVID-19 Severity in Patients.” The Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 218, no. 3, Nov. 2020, p. e20201707. PubMed Central, doi:10.1084/jem.20201707.

Roncero-Ramos, Irene, et al. “Mediterranean Diet, Glucose Homeostasis, and Inflammasome Genetic Variants: The CORDIOPREV Study.” Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, vol. 62, no. 9, May 2018, p. e1700960. PubMed, doi:10.1002/mnfr.201700960.

Santos, Juliana Carvalho, et al. “The Impact of Polyphenols-Based Diet on the Inflammatory Profile in COVID-19 Elderly and Obese Patients.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 11, Jan. 2021, p. 612268. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.612268.

Shao, Bo-Zong, et al. “NLRP3 Inflammasome and Its Inhibitors: A Review.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 0, 2015. Frontiers, doi:10.3389/fphar.2015.00262.

Shen, Zheni, et al. “The Role of Cardiolipin in Cardiovascular Health.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2015, Aug. 2015, p. e891707. www.hindawi.com, doi:10.1155/2015/891707.

Suryavanshi, Santosh V., et al. “Cannabinoids as Key Regulators of Inflammasome Signaling: A Current Perspective.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 11, Jan. 2021, p. 613613. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.613613.

—. “Cannabinoids as Key Regulators of Inflammasome Signaling: A Current Perspective.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 11, Jan. 2021, p. 613613. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.613613.

Xia, Xiaojing, et al. “The Role of Pyroptosis in Cancer: Pro-Cancer or pro-‘Host’?” Cell Death & Disease, vol. 10, no. 9, Sept. 2019, pp. 1–13. www.nature.com, doi:10.1038/s41419-019-1883-8.

Yerramothu, P., et al. “Inflammasomes, the Eye and Anti-Inflammasome Therapy.” Eye, vol. 32, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 491–505. PubMed Central, doi:10.1038/eye.2017.241.

Zhang, An-Qiang, et al. “Clinical Relevance of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms within the Entire NLRP3 Gene in Patients with Major Blunt Trauma.” Critical Care, vol. 15, no. 6, 2011, p. R280. PubMed Central, doi:10.1186/cc10564.

Zhang, Q., et al. “NLRP3 Rs35829419 Polymorphism Is Associated with Increased Susceptibility to Multiple Diseases in Humans.” Genetics and Molecular Research: GMR, vol. 14, no. 4, Oct. 2015, pp. 13968–80. PubMed, doi:10.4238/2015.October.29.17.