Key takeaways:

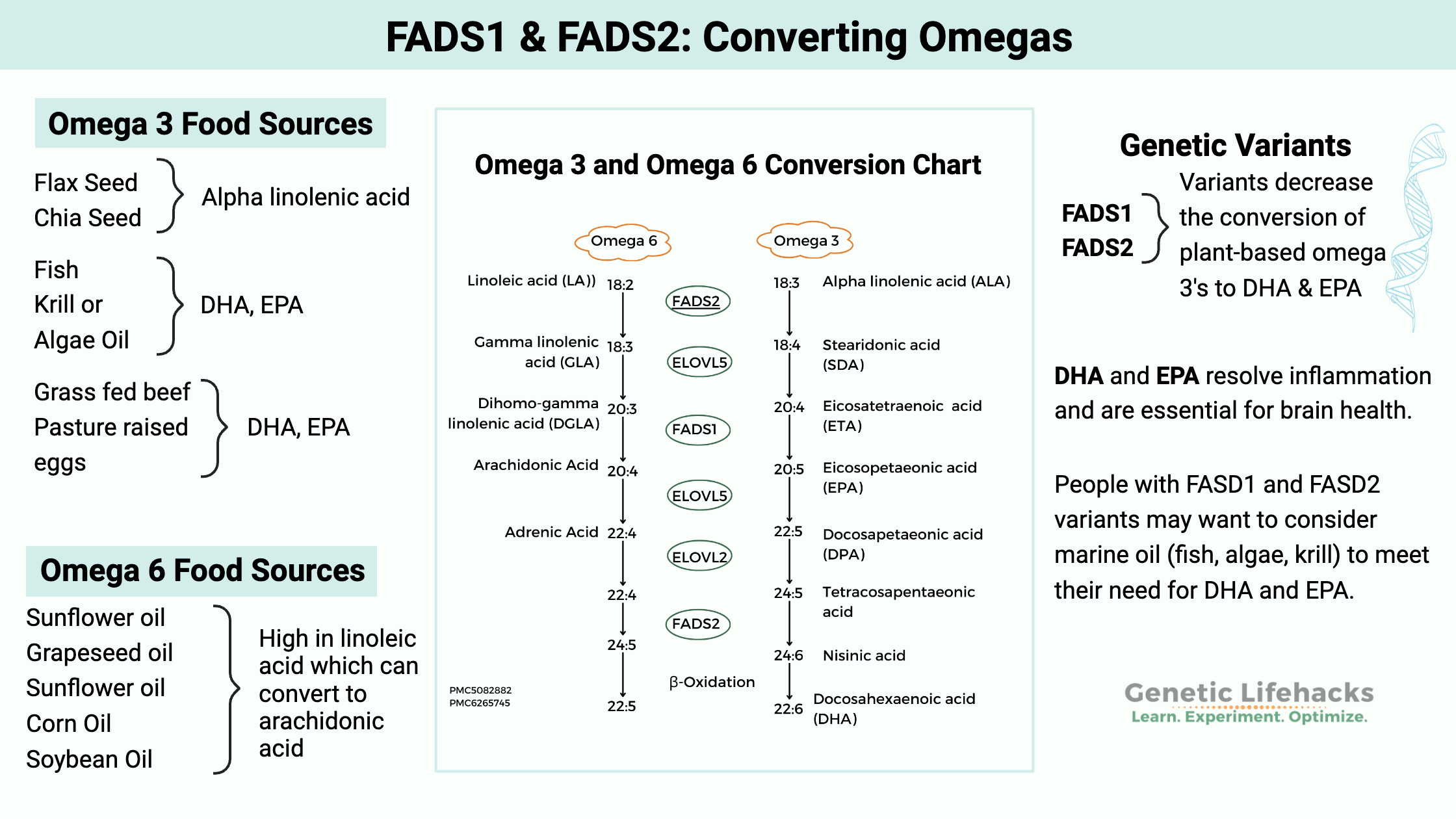

~ Polyunsaturated fats are transformed using the FADS1 and FADS2 enzymes.

~ Genetic variants impact how well you convert omega-3 fatty acids, such as from plants, into DHA and EPA. These variants also impact how likely you are to convert omega-6 oils into arachidonic acid, which can be proinflammatory.

~ Understanding your genetic variants can help you understand the best form of omega-3s for you.

Polyunsaturated Fats: Omega-3 and Omega-6

Fats are made up mainly of hydrogen and carbon molecules. They are categorized as saturated or unsaturated based on their carbon bonds.

Saturated fats have all of their carbons bound to hydrogens, while unsaturated fats don’t have all of their carbon bonds filled with hydrogen, allowing for carbon-carbon bonds.

- Saturated fats form straight chains that are tightly packed together, resulting in solids at room temperature (e.g., coconut oil, butter).

- Unsaturated fats, with a bend at their carbon-carbon bond, pack less tightly together and become liquids at room temperature (e.g., olive oil).

Omega-6 fatty acids are named because the double carbon-carbon bond is the sixth bond, while omega-3 fatty acids have a double bond as the third bond. You will also find the omega-3 fatty acid written as ω−3 or n−3. Same for omega-6 (ω−6 or n−6).

Seed oils high in Omega-6 fatty acids include:

- corn

- safflower

- grapeseed

- sunflower

- cottonseed

- soybean

- walnut

Plant oils high in omega-3 include flaxseed oil and chia seeds. Fish oil, krill oil, and algae oil (marine oils) contain abundant longer-chain omega-3 fatty acids, EPA, and DHA.

Most people carry genetic variants enabling them to use plant-based polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). What is thought to be the ancestral genotype that doesn’t convert plant-based PUFAs now shows up in a minority of people. People with these FADS1 and FADS3 variants have a hard time if they rely on plant-based fats because they may lack the ability to convert the omega-3s to brain-healthy DHA and EPA.

Why do we need polyunsaturated fats?

Fatty acids, including both saturated and polyunsaturated fats, make up the membrane surrounding each cell in the body. The body also uses omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids to make eicosanoids (pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules), pro-resolving lipid mediators, endocannabinoids, and cellular signaling molecules.

While both omega 6 and omega 3 fats are essential, there has been a recent shift in how much omega 6 fats are in our diets.

Omega 6: Omega 3 ratio in Modern Diets

Most nutritionists agree that the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids is important to our health. Current thought suggests our ancestors ate a diet with a ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 of less than 4:1 and maybe even as low as 1:1.[ref]

Currently, an average Western diet has a ratio of 16:1 or higher of omega-6 to omega-3 consumption. Omega-6 fats can have both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties, and it is thought that the modern imbalance of omega-6 to 3 may be causing an increase in inflammatory diseases such as heart disease and diabetes.[ref]

You are what you eat, and a recent study makes it clear that most of us have a lot more omega-6 in our fat cells than people did fifty years ago. Our modern diet has led to a 136% increase in the amount of linoleic acid (an omega-6 fat) in our adipose tissue.[ref]

Going in-depth on Omega 6s:

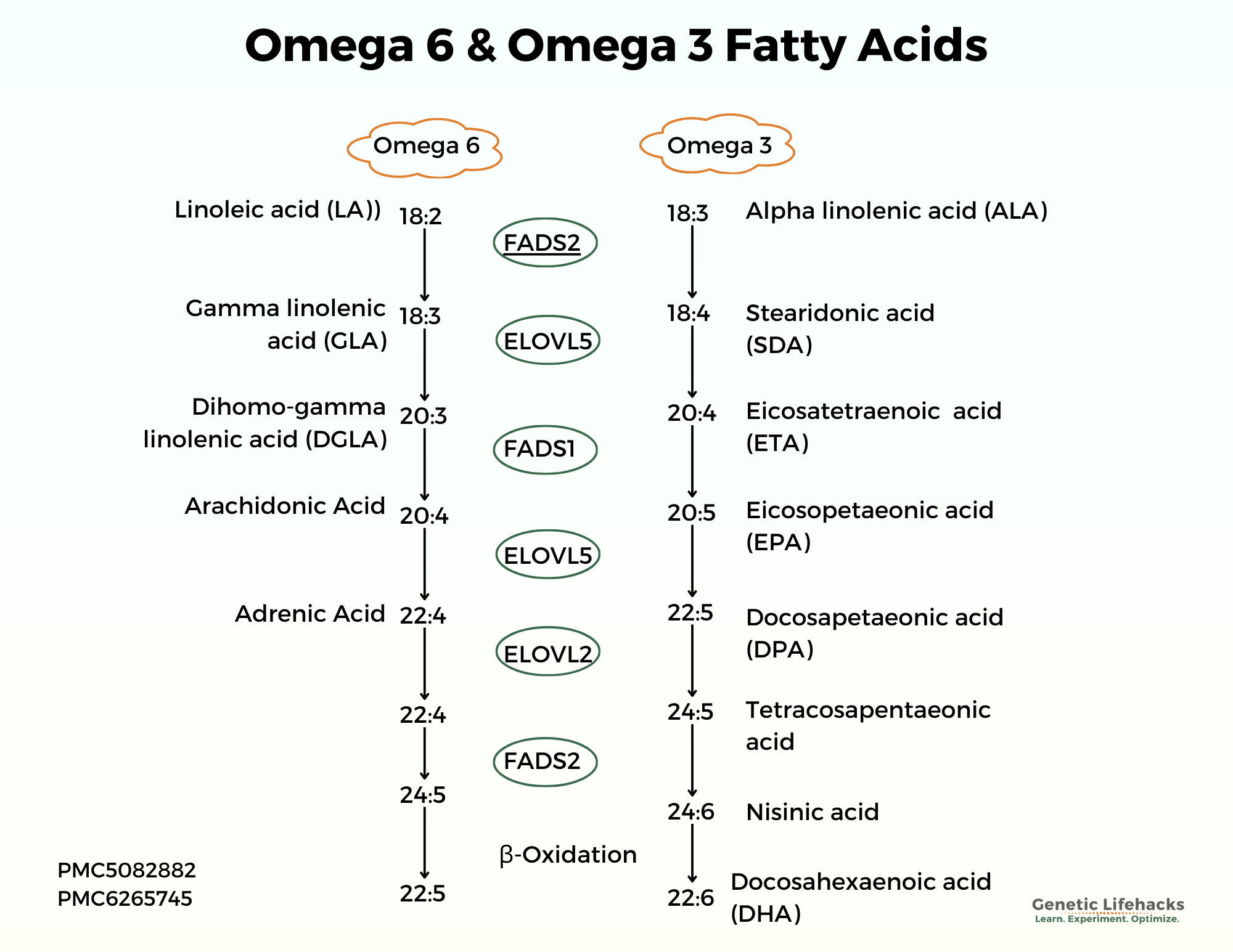

There isn’t just one “Omega-6” fat. The term applies to a series of different chains of fatty acids, defined by the length of the carbon-hydrogen chain.

The omega-6 fatty acids you eat in foods are generally linoleic or gamma-linolenic acid and our bodies change them into arachidonic acid, eicosatetraenoic acid, and docosapentaenoic acid. This conversion uses enzymes called fatty acid desaturase (coded for by the FADS1 and FADS2 genes).

For example, if you eat a plant-based oil high in omega-6 fats (sunflower, cottonseed, corn, etc.), you are consuming it in the form of linoleic acid. Linoleic acid can then be converted by FADS1 and FADS2 (in a couple of steps) to arachidonic acid.

Arachidonic acid can be pro-inflammatory under some conditions, but it can also be beneficial in building muscle mass for weight lifters.[ref] Arachidonic acid also leads to higher eicosanoids, which are important in allergic inflammation.[ref]

Here’s an overview of the genes involved in PUFA conversion.

Omega 3 transformations

Your body also transforms omega-3 fatty acids from the shorter-chained fatty acids found in plants (alpha-linolenic acid) into longer-chained fatty acids such as EPA and DHA.

Most plant sources of omega-3, such as flaxseed and chia seeds, are in the form of alpha-linolenic acid. A small percentage of alpha-linolenic acid changes via the enzymes produced by FADS1 and FADS2 genes into eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). More on this is in the genetics section.

To get EPA and DHA without converting alpha-linolenic acid, you must consume animal products such as fish oil, krill oil, or oily fish. Relatively new to the market are specially formulated algae oil supplements that also provide DHA and EPA.

Why are DHA and EPA so essential? In addition to their role in heart health and brain health, these marine oil-derived omega-3s are the foundational molecules forming pro-resolving lipid mediators. Recently, researchers have figured out that the resolution of inflammation is actually an active process that relies on specific pro-resolving lipid mediators derived from DHA and EPA.

Related article: Specialized Pro-resolving lipid mediators

Shared enzymes: FADS1 and 2 convert both Omega 6s and 3s.

The metabolism of both the omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids involves the same FADS1 and FADS2 enzymes.

This is where the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fats in your diet comes into play. With only a limited amount of these desaturase enzymes available, a high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 means more of the omega-6 will be metabolized into arachidonic acid, and less EPA and DHA will be produced.

The FADS1 (encodes delta-5 desaturase) and FADS2 (encodes delta-6 desaturase) genes have several different variants that slow down the production of the enzymes.

So what does slowing the production of these enzymes mean for your body? It depends on how much omega-6 and omega-3 you consume.

If you eat a diet high in omega-6, having less linoleic acid (omega-6) turning into the sometimes inflammatory arachidonic acid due to having less of an enzyme can be good. However, on the omega-3 side, this situation also produces less EPA and DHA if your diet is heavy on omega-6 fatty acids. One way around this is to eat very little omega-6 fat; another way is to directly get EPA and DHA from fish or fish oil.

Less pro-resolving and more pro-inflammatory mediators:

As I mentioned above, keep in mind that the resolution of inflammation is an active process that depends on the availability of DHA and EPA. Similarly to the conversion of omega-6 and omega-3s to longer-chain fatty acids, the conversion of DHA and EPA to pro-resolving lipid mediators involves enzymes that are also used to convert omega-6 fatty acids to inflammatory mediators.

Quite a few studies have found that those with variants that slow down the conversion of linoleic acid to arachidonic acid affect disease risks. A 2008 study found that those with higher arachidonic acid to linoleic acid ratios had a higher risk of coronary artery disease.[ref] Conversely, those with variants slowing down the FADS enzymes can have a lower risk of heart disease.

FADS1 and FADS2 Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

As I mentioned above, the body uses the same enzymes to convert both omega-6 and 3 to the longer chain forms needed in the body. The ratio between omega-6 and omega-3 intake is important for everyone, but it may be significant for people carrying the FADS variant. In general, most people with the FADS1/2 variants probably need to shift their diets away from too much omega-6 and increase DHA/EPA (omega-3) from fish oil.

Limiting omega-6s and increasing omega-3s

Our modern diets tend to be high in omega-6 seed oils, which you may want to decrease if it is out of balance with the amount of omega-3 fats you consume. Oils that are high in omega-6 linoleic acid that you may want to avoid:

- safflower

- grapeseed

- sunflower

- corn

- walnut

- wheat germ

- cottonseed

- soybean

- sesame

- peanut

Foods high in these oils include most mayonnaises, salad dressings, margarine, walnuts, sunflower seeds, and peanut butter. Pretty much anything that is fried is high in omega-6 oils.[ref]

Foods and oils that are high in omega-3, which you may want to increase, include:

- fish oil (DHA, EPA)

- fatty fish

- seal oil

- flax seed (alpha-linolenic acid) (must be converted with FADS enzyme)

- chia seeds (must be converted with FADS enzyme)

- caviar

Ancestral Diets:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Do you carry the Hunter-Gatherer or the Farmer Genetic Variant

References:

AlSaleh, Aseel, et al. “Genetic Predisposition Scores for Dyslipidaemia Influence Plasma Lipid Concentrations at Baseline, but Not the Changes after Controlled Intake of n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids.” Genes & Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 4, July 2014, p. 412. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-014-0412-8.

Bokor, Szilvia, et al. “Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the FADS Gene Cluster Are Associated with Delta-5 and Delta-6 Desaturase Activities Estimated by Serum Fatty Acid Ratios.” Journal of Lipid Research, vol. 51, no. 8, Aug. 2010, pp. 2325–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M006205.

Braarud, Hanne Cecilie, et al. “Maternal DHA Status during Pregnancy Has a Positive Impact on Infant Problem Solving: A Norwegian Prospective Observation Study.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 5, Apr. 2018, p. 529. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10050529.

Carlson, Susan E., et al. “DHA Supplementation and Pregnancy Outcomes.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 97, no. 4, Apr. 2013, pp. 808–15. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.050021.

Dumont, Julie, Louisa Goumidi, et al. “Dietary Linoleic Acid Interacts with FADS1 Genetic Variability to Modulate HDL-Cholesterol and Obesity-Related Traits.” Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), vol. 37, no. 5, Oct. 2018, pp. 1683–89. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2017.07.012.

Dumont, Julie, Inge Huybrechts, et al. “FADS1 Genetic Variability Interacts with Dietary A-Linolenic Acid Intake to Affect Serum Non-HDL–Cholesterol Concentrations in European Adolescents12.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 141, no. 7, July 2011, pp. 1247–53. jn.nutrition.org, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.140392.

Forsyth, Stewart, et al. “The Importance of Dietary DHA and ARA in Early Life: A Public Health Perspective.” The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, vol. 76, no. 4, Nov. 2017, pp. 568–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665117000313.

Gieger, Christian, et al. “Genetics Meets Metabolomics: A Genome-Wide Association Study of Metabolite Profiles in Human Serum.” PLOS Genetics, vol. 4, no. 11, Nov. 2008, p. e1000282. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000282.

Guyenet, Stephan J., and Susan E. Carlson. “Increase in Adipose Tissue Linoleic Acid of US Adults in the Last Half Century.” Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), vol. 6, no. 6, Nov. 2015, pp. 660–64. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.009944.

He, Zhen, et al. “FADS1-FADS2 Genetic Polymorphisms Are Associated with Fatty Acid Metabolism through Changes in DNA Methylation and Gene Expression.” Clinical Epigenetics, vol. 10, no. 1, Aug. 2018, p. 113. BioMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-018-0545-5.

Hellstrand, S., et al. “Intake Levels of Dietary Long-Chain PUFAs Modify the Association between

genetic Variation in FADS and LDL-C.” Journal of Lipid Research, vol. 53, no. 6, June 2012, pp. 1183–89. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.P023721.

Juan, Juan, et al. “Joint Effects of Fatty Acid Desaturase 1 Polymorphisms and Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intake on Circulating Fatty Acid Proportions.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 107, no. 5, May 2018, pp. 826–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy025.

Kwong, Raymond Y., et al. “Genetic Profiling of Fatty Acid Desaturase Polymorphisms Identifies Patients Who May Benefit from High-Dose Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Cardiac Remodeling after Acute Myocardial Infarction—Post-Hoc Analysis from the OMEGA-REMODEL Randomized Controlled Trial.” PLOS ONE, vol. 14, no. 9, Sept. 2019, p. e0222061. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222061.

Lager, Susanne, et al. “Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation in Pregnancy Modulates Placental Cellular Signaling and Nutrient Transport Capacity in Obese Women.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 12, Dec. 2017, pp. 4557–67. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01384.

Lemaitre, Rozenn N., et al. “Genetic Loci Associated with Plasma Phospholipid N-3 Fatty Acids: A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies from the CHARGE Consortium.” PLoS Genetics, vol. 7, no. 7, July 2011, p. e1002193. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002193.

Li, Si-Wei, et al. “Polymorphisms in FADS1 and FADS2 Alter Plasma Fatty Acids and Desaturase Levels in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Coronary Artery Disease.” Journal of Translational Medicine, vol. 14, Mar. 2016, p. 79. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-0834-8.

Markworth, James F., et al. “Arachidonic Acid Supplementation Modulates Blood and Skeletal Muscle Lipid Profile with No Effect on Basal Inflammation in Resistance Exercise Trained Men.” Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids, vol. 128, Jan. 2018, pp. 74–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2017.12.003.

Martinelli, Nicola, et al. “FADS Genotypes and Desaturase Activity Estimated by the Ratio of Arachidonic Acid to Linoleic Acid Are Associated with Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 88, no. 4, Oct. 2008, pp. 941–49. ajcn.nutrition.org, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/88.4.941.

Mychaleckyj, Josyf C., et al. “Multiplex Genomewide Association Analysis of Breast Milk Fatty Acid Composition Extends the Phenotypic Association and Potential Selection of FADS1 Variants to Arachidonic Acid, a Critical Infant Micronutrient.” Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 55, no. 7, July 2018, pp. 459–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105134.

Park, Sunmin, et al. “Carrying Minor Allele of FADS1 and Haplotype of FADS1 and FADS2 Increased the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Moderate but Not Low Fat Diets Lowered the Risk in Two Korean Cohorts.” European Journal of Nutrition, vol. 58, no. 2, Mar. 2019, pp. 831–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1719-9.

Scholtz, SA, et al. “Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Supplementation in Pregnancy Differentially Modulates Arachidonic Acid and DHA Status across FADS Genotypes in Pregnancy–.” Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids, vol. 94, Mar. 2015, pp. 29–33. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2014.10.008.

Simopoulos, A. P. “The Importance of the Ratio of Omega-6/Omega-3 Essential Fatty Acids.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie, vol. 56, no. 8, Oct. 2002, pp. 365–79. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0753-3322(02)00253-6.

Tanaka, Toshiko, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Plasma Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the InCHIANTI Study.” PLoS Genetics, vol. 5, no. 1, Jan. 2009, p. e1000338. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000338.

Trebatická, J., et al. “Cardiovascular Diseases, Depression Disorders and Potential Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids.” Physiological Research, vol. 66, no. 3, July 2017, pp. 363–82. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.933430.