Key takeaways:

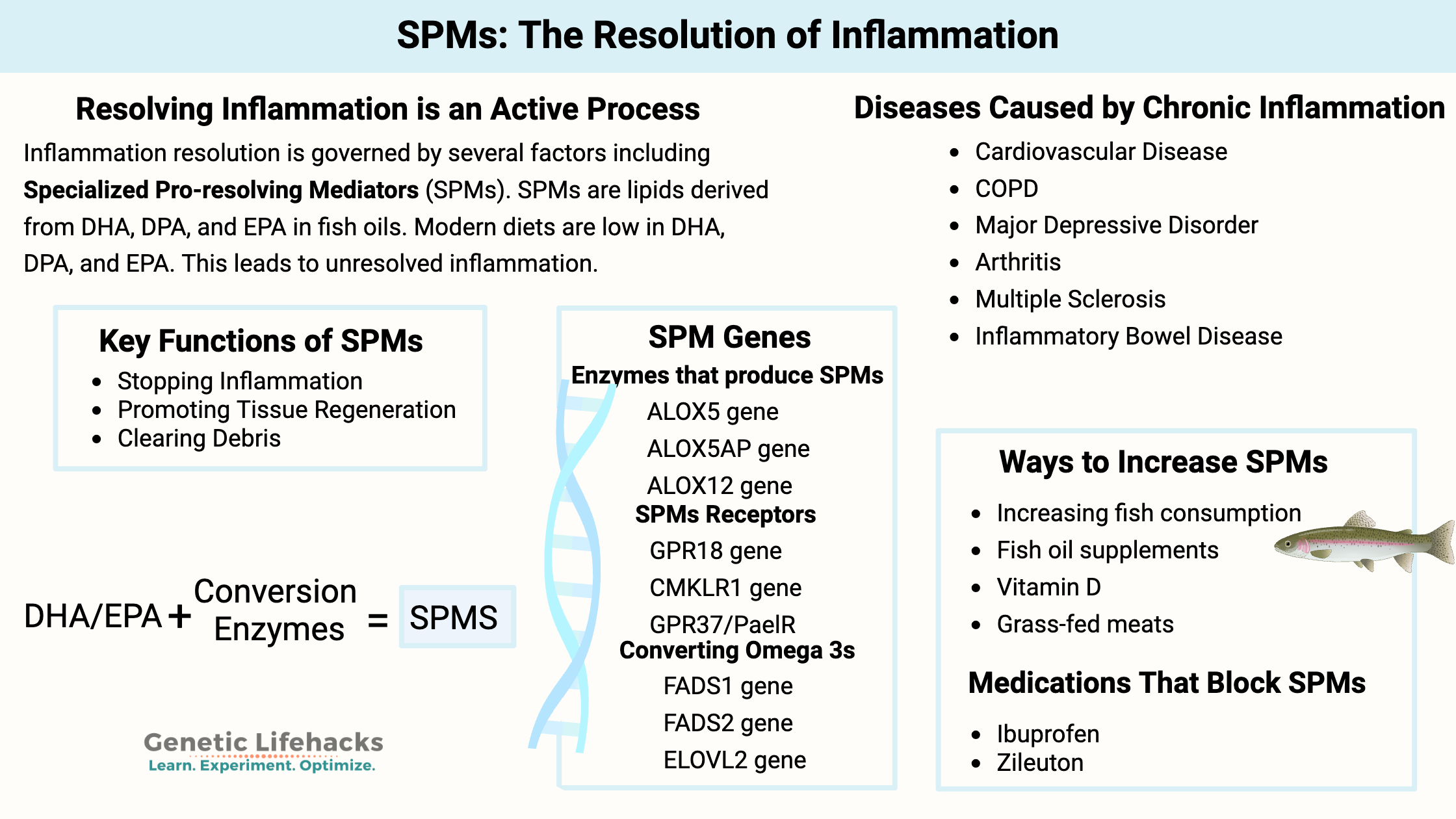

- Resolving inflammation is an active process: The body doesn’t just let inflammation fade away; it actively produces specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) to end inflammation and restore tissue health

- SPMs are lipid molecules synthesized from dietary omega-3s—mainly DHA and EPA—which are often lacking in modern diets.

- A lack of pro-resolving mediators can allow inflammation to continue, leading to many chronic diseases.

- Genetic variants can affect how efficiently your body converts dietary fats into SPMs, meaning some people may need more DHA/EPA or benefit from specific supplement forms.

Chronic disease, unresolved inflammation, and prevention

In the U.S., 60% of adults have been diagnosed with a chronic disease, and 40% have two or more conditions – that’s a lot of unhealthy people. Most chronic diseases have persistent, low-level inflammation as their underlying cause.[ref]

Diseases rooted in chronic inflammation include:[ref][ref]

| Disease/Condition | Connection to Inflammation/Resolution Deficit |

|---|---|

| Heart disease | Persistent inflammation, lack of SPMs |

| Alzheimer’s | Chronic inflammation, SPMs involved in clearance |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Elevated cytokines, insufficient resolution |

| Type 2 diabetes | Impaired SPM receptor function |

| Neuropathic pain | SPMs modulate pain pathways |

| Mood disorders | Inflammation, SPMs linked to symptom improvement |

| IBD (Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis) | Defective SPM biosynthesis |

| Obesity, fatty liver disease | Chronic inflammation, SPMs reduce adipose inflammation |

| Multiple sclerosis | Impaired SPM biosynthesis, disease progression |

| Chronic kidney disease | Low SPMs, persistent inflammation |

| Arthritis (other forms) | Low SPMs, pain, and inflammation |

| Cancer | Poor resolution, SPMs in tumor microenvironment |

| Asthma | Lower protectin D1, airway inflammation |

| Tissue fibrosis | SPMs promote tissue regeneration |

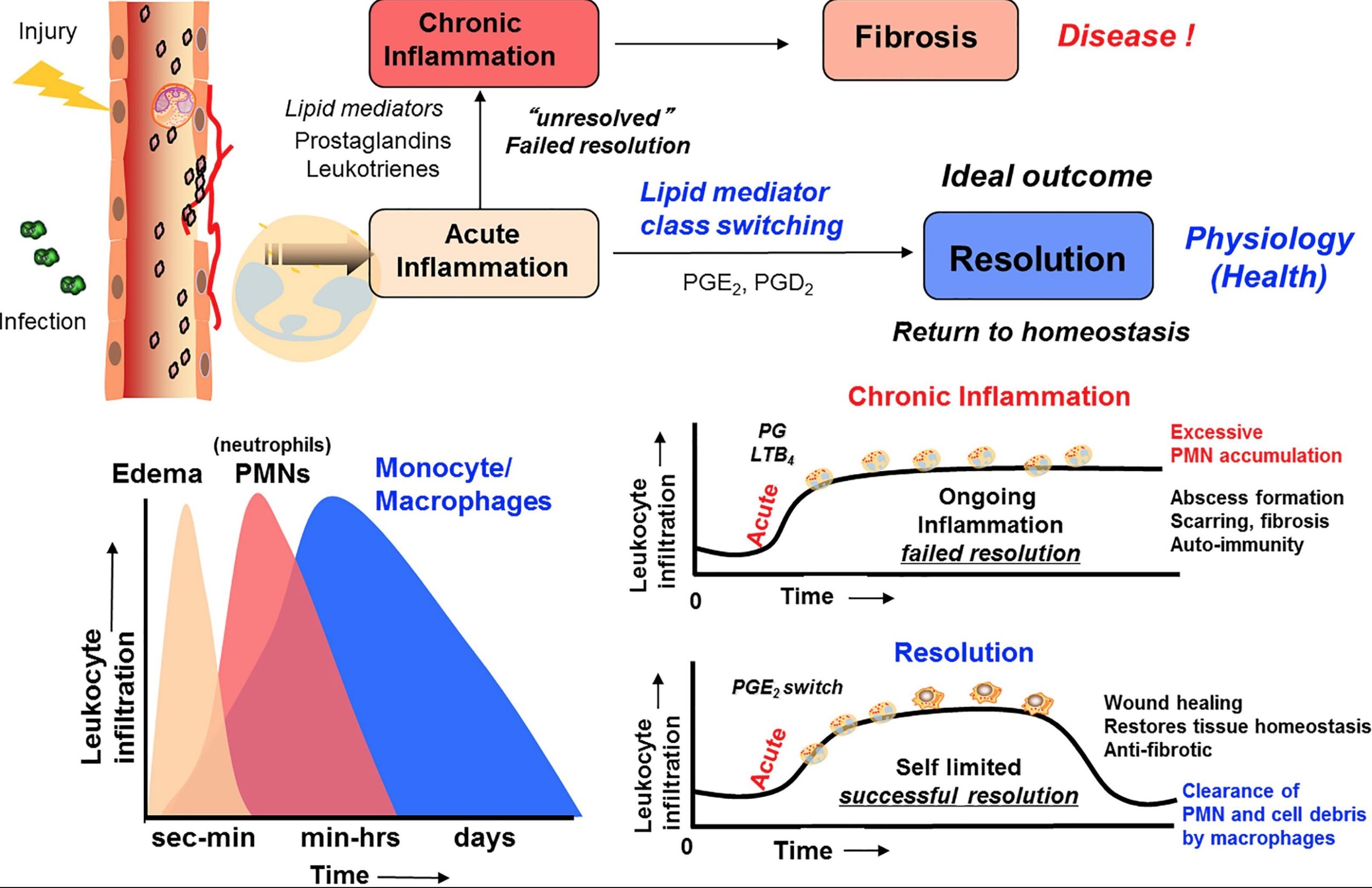

Chronic inflammation is a big problem, but… inflammation is only half the story. Over the past decade or so, researchers have discovered the mechanisms through which inflammation is resolved. This paradigm-shifting research can be summed up as:

The resolution of inflammation is an active process.

Inflammation doesn’t just fade away like doctors used to think. Instead, the resolution of inflammation is an active process. Pro-resolution molecules are produced to both halt the inflammatory processes and initiate a bunch of processes to clean up and return the tissue to homeostasis.

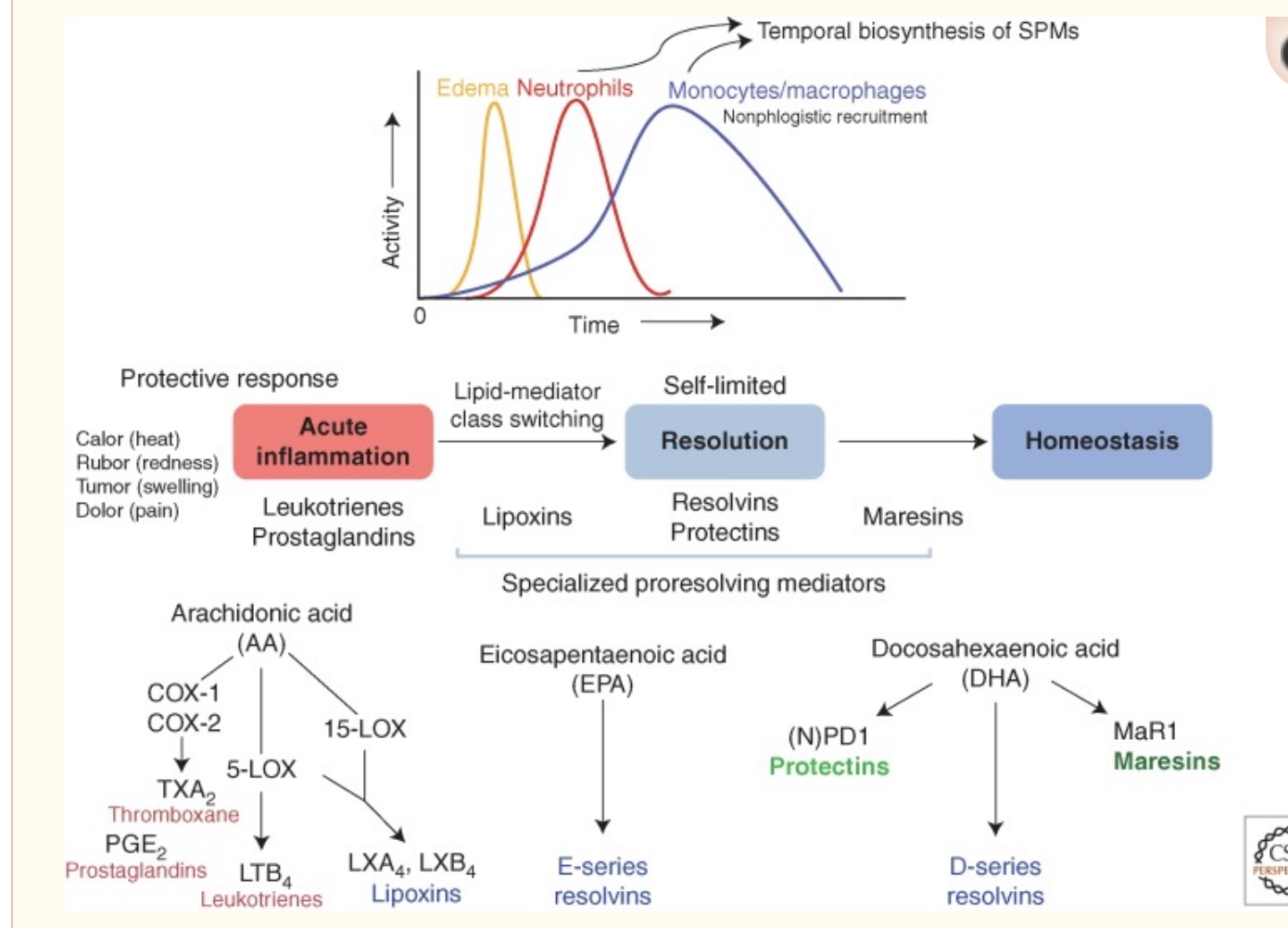

These molecules are called specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs). They are lipids (fatty acids) that signal for the resolution of inflammation.

Importantly, these SPMs are synthesized from the omega-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA, which are often lacking in modern diets.

To be clear: Specialized pro-resolving mediators and the active process of resolving inflammation are different from anti-inflammatory drugs or supplements that block inflammation. While antioxidants and anti-inflammatory supplements can be helpful, they only address the suppression of inflammation, not the complete resolution and return to health.

Before we get into the pro-resolving mediators, let’s take a quick trip through the basics of inflammation and talk about a few key players.

Inflammation: Quick Overview

The immune system is ready to respond when you get a cut, are infected by bad bacteria, or break a bone.

When an insult occurs – a cut, a pathogen, or an injury – a cascade of inflammatory events is set in motion.

White blood cells, also called leukocytes, are a type of immune cell that protects the body from invaders. White blood cells (leukocytes) originate in the bone marrow from hematopoietic stem cells. Leukocyte is a general term. There are specific subtypes of white blood cells, including neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes (which become macrophages). They all play a role in inflammation and in protecting your body from infection.

Inflammation is classically characterized by warmth, swelling, redness, and pain. (Calor, Dolor, Rubor, and Tumor, if you like it in Latin)[ref] These signs of inflammation are due to increased blood flow, capillary dilation (swelling), leukocyte infiltration, and the production of inflammatory cytokines.

Example:

You get a piece of wood stuck in your finger. It becomes swollen, painful, and red. Pus with lots of white blood cells may collect where the splinter was. You eventually get the tiny piece of wood out of your finger, and the next day your finger is back to normal-no more redness, swelling, or pain.

What happened? The foreign object (a sliver of wood), cell damage, and bacteria were detected. Neutrophils rushed in, and inflammatory cytokines were released, causing vasodilation and fluid to rush into the area. More inflammatory cytokines were recruited, mast cells released their mediators, macrophages engulfed the bacteria on the splinter, ROS were produced to kill the bacteria, and then… resolution. Back to normal.

Until recently, scientists didn’t realize that the resolution of inflammation was much more than just the cytokines passively slipping away and the immune system cells retreating.

Concurrent with acute inflammation is the onset of the resolution of inflammation. Pro-resolving mediators are produced by immune system cells to actively cause the resolution of inflammation and healing back to normal. It happens at the same time as inflammatory processes.

Chronic inflammation is due to a lack of resolution

Anti-inflammatory drugs are often prescribed for chronic diseases. For example, NSAIDs or leukotriene inhibitors block the production of inflammatory cytokines. Biologics that block TNF, such as anti-TNF antibodies, are used to reduce the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, side effects include a suppressed immune system that makes patients more susceptible to pathogens.

But why do inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha stay elevated in RA? One big part of the picture seems to be an inadequate or insufficient resolution of the inflammation.

One study explains: “While it was previously thought that passive disappearance of pro-inflammatory factors was sufficient for the cessation of inflammation, it is now known that the resolution of acute inflammation (or inflammation-resolution) is an active and highly coordinated process. Inflammation resolution is governed by a panoply of endogenous factors that include SPMs, protein/peptide mediators such as annexin A1 and interleukin 10, gases such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide, and nucleotides such as adenosine and inosine.”[ref]. (We’ll stick to talking about SPMs here, but keep in mind that, as in-depth as SPMs are, there’s more to the topic.)

SPMs (specialized pro-resolving mediators) are not only important in halting the inflammatory response, but they also “orchestrate the clearance of tissue pathogens, dying cells, and debris from the battlefield of infectious inflammation.”[ref]

This isn’t just about chronic disease. SPMs are also important in turning off the immune response and returning the body to normal after a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection. The lack of pro-resolving mediators is thought to be a cause of severe COVID-19 symptoms such as acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Macrophages in the Immune Response:

Macrophages are important players in inflammation. They are a specialized type of leukocyte (white blood cell) that can differentiate into two different forms.

- M1 form: pro-inflammatory, producing high levels of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1ß, IL-6, IL-12.

- M2 form: anti-inflammatory, and a big part of the resolution of inflammation.

The M2 form of the macrophage is programmed by the SPMs and cleans up the inflammation, engulfing and removing the remaining inflammatory debris.[ref]

In all, the resolution of inflammation by SPMs includes:[ref]

- Removal of microbes, dead cells, and debris

- Restoration of the integrity of blood vessels

- Regeneration of tissues

- Remission of fever

- Relief of pain

Low SPMs in Chronic Disease:

The final point to drive home here: people with chronic inflammatory diseases have lower pro-resolving mediator levels that are specific to the resolution of their chronic condition.[ref]

Chronic disease isn’t just the low levels of continuing inflammation; it is also the lack of clean-up and restoration. The house burned down (acute inflammation), and not only did the remains still smolder, but there was also no clean-up crew to remove the mess and rebuild.

Here is a screenshot from a great Frontiers in Immunology article that sums up the process of resolution of inflammation:

Let’s dig into the details of what is currently known about the resolution of inflammation.

Lipid mediators: What are they?

We often think of the fats (lipids) that we eat as just something that produces energy — or something that makes you fat when it comes to eating fried donuts.

Energy production or fat storage are just two of the many functions of fat in the body. For example, lipids (fats) also make up the cell membrane surrounding the trillions of cells in your body, and lipids are also essential for creating certain hormones.

Lipid is a general term for fats, including the fatty acids that we are familiar with eating (saturated, unsaturated, long chains and short). Fatty acids are chains of hydrogens and carbons. They are categorized by the bonds, such as all saturated bonds or with an unsaturated bond at a certain spot (e.g., omega-6 or omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids).

In addition to being used for creating cellular energy, certain lipids act as signaling molecules, which means that they can bind with a receptor and cause something to happen in a cell.

Specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) are lipids derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Creation of the specialized pro-resolving mediators

The SPMs are produced using polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) as the base molecules. Specifically, DHA and EPA are the precursors for many SPMs, and arachidonic acid (AA) is also a precursor. DHA and EPA are omega-3 PUFAs found in fish oil. Arachidonic acid is an omega-6 fatty acid found in meat and plant oils.

These precursors come from eating foods that contain the needed omega-3 and omega-6s. The precursor fatty acids are then converted by specific enzymes produced by certain cell types when triggered by acute inflammation.[ref]

There are five types of pro-resolving lipid mediators:

| SPM Type | Precursor Fatty Acid | Key Subtypes | Main Functions/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipoxins | Arachidonic acid | Lipoxin A4, B4 | Early resolution, heart/brain protection, lung repair |

| Resolvins | EPA, DHA, DPA | RvE1-4, RvD1-6, RvT1-4 | Atherosclerosis, neuroprotection, infection clearance, pain |

| Protectins | DHA, DPA | Protectin D1, D2 | Switch macrophages to M2, reduce Alzheimer’s plaques, asthma |

| Maresins | DHA | MaR1, MaR2, eMaR | Tissue regeneration, bone health, pain modulation |

| Cysteinyl SPMs | DHA | MCTR1-3, PCTR1-3, RCTR1-3 | Tissue regeneration, cardiovascular protection |

1) Lipoxins

Lipoxins are derived from arachidonic acid (omega-6 fatty acid) and are created at the onset of inflammation. The pro-resolution processes start almost as soon as acute inflammation begins.

While the majority of specialized pro-resolving mediators are derived from omega-3 fatty acids (DHA and EPA), lipoxin is the outlier and is formed from the conversion of an omega-6 fatty acid, arachidonic acid (AA). There are several lipoxin types, named lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4.

Here are a few examples of what lipoxins do:

- Lipoxins are important in preventing heart disease via the resolution of inflammation in atherosclerosis.[ref]

- Lipoxins are important in protecting the brain in neurodegeneration and glaucoma.[ref]

- After a stroke, lipoxins are important in resolving inflammation.[ref]

2) Resolvins

Resolvins derived from EPA are named RvE1 through RvE4 (resolvin E1, etc.). Resolvins derived from DHA are called the D-series. They are named RvD1 through RvD6.[ref] Resolvins derived from DPA, another omega-3 fatty acid, include RvT1, RvT2, RvT3, RvT4. The details aren’t important here – I’m just wanting to drive home the point that there are multiple resolvins derived from omega-3 fatty acids.

What do resolvins do?

- After a stroke, RevD1 is important in resolving inflammation.[ref]

- Resolvin E1 is important in protecting against atherosclerosis, carotid artery disease, and clearance of tumor cell debris. Resolvin D5 is important in clearing out bacterial pathogens.[ref][ref]

- Animal studies show the potential of resolvin E1 and D1 in neurodegenerative diseases.[ref]

- Resolvin D2 is important in periodontal disease in preventing bone loss.[ref]

3) Protectins

Protectin D1 is derived from DHA, while protectin D2 is synthesized from DPA (another omega-3 fatty acid).[ref] Protectins are important in switching macrophages from the proinflammatory to the anti-inflammatory type.[ref] As I mentioned above, macrophages can increase inflammation (M1 type), or they can clean up and stop inflammation (M2 type). Protectins can initiate the switch to M2 type.

- In animal studies, protectin D1 is important in reducing the amyloid-beta plaque, which causes Alzheimer’s disease.[ref]

- Protectin D1 is important in the cornea to protect from injury and in the retina.

- Protectins are also important in resolving inflammation in adipose (fat) tissue. Chronic inflammation goes hand-in-hand with obesity, and protectins have reversed the inflammation.[ref]

- Protectin D1 also dampens hyperactivity in the airways. People with asthma have lower levels of protectin D1.[ref]

4) Maresins (derived from DHA)

Maresins are also derived from DHA and abbreviated MaR1, MaR2, and eMaR. Maresins are important for:

- Tissue regeneration and bacterial infections.[ref]

- Pain sensitivity and bone regeneration.[ref]

- Bone health. Low maresin 1 is found in osteoporosis.[ref]

- Inhibiting the activation of NF-κB, improving Treg/Th17 imbalance, and alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress.[ref]

- Maresin 1 pretreatment (animal study) shows that it stops UVB damage.[ref]

- Maresin 1 helps ameliorate fibrosis and heal muscle loss from trauma/surgery.[ref]

5) Cysteinyl SPMs

Discovered within the past couple of years, cysteinyl SPMs are also derived from DHA and are peptides conjugated with the other lipid mediators. The family of cysteinyl SPMs includes MCTR1, MCTR2, MCTR3, PCTR1, PCTR2, PCTR3, RCTR1, RCTR2, RCTR3. They are involved in tissue regeneration and cardiovascular protection.[ref]

Conversion enzymes: Biosynthesis of SPMs

The precursor molecules for the lipid mediators are pretty straightforward and easy to understand: DHA, DPA, and EPA, which are omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids found in fish oil, and Arachidonic Acid (AA), which is an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid.

You need enough of the precursor fatty acids to make the lipid mediators. If you never get any DHA/EPA in your diet, you are likely behind the 8-ball when it comes to producing pro-resolving lipid mediators. But what if you are eating fish daily? Getting enough arachidonic acid… Doing it right for the precursors?

The precursor fatty acids still need to be converted into the SPMs via enzymatic processes, and then they need the receptors available to bind to and complete their pro-resolution actions.

Here’s an overview of what is going on here:

| Step/Component | Details/Genes Involved | Notes/Variants Affecting SPMs |

|---|---|---|

| Omega-3/6 Intake | DHA, EPA, DPA, AA (from diet) | Modern diets often low in omega-3 |

| Conversion Enzymes | 5-LOX (ALOX5), 12-LOX (ALOX12), 15-LOX (ALOX15), COX2 | Genetic variants affect enzyme efficiency |

| Key Genes | FADS1, FADS2, ELOVL2, ALOX5, ALOX5AP, ALOX12, COX2 | Variants can reduce conversion or increase risk |

| Receptors | FPR2, GPR37, GPR18, CMKLR1, LGR6 | Variants affect SPM signaling and disease risk |

The enzymes that convert DHA, EPA, and DPA into the SPMs include 5-LOX, 12-LOX, and 15-LOX.

- The ALOX12 and ALOX15 genes encode 12-LOX and 15-LOX, which convert DHA and DPA into the D-series resolvins, protectins, and maresins.[ref]

- The ALOX5 gene encodes the 5-LOX enzyme that is also needed in the conversion of the D-series resolvins, as well as the E-series resolvins and DPA-derived resolvins.

Cell studies show that when lower amounts of these enzymes are produced, there is more chronic inflammation. One study looked at the role of SPMs in tendonitis, which is common in people with diabetes. The diabetic tendon samples showed chronic inflammation plus low levels of the enzymes needed to produce the pro-resolution lipid mediators.[ref]

Omega-6 to Omega-3 ratio and bioactive lipids:

I’ve mentioned several times that there’s been a shift in our modern diet to eating more omega-6 fatty acids (corn oil, soybean oil, etc) and less omega-3. Part of the problem is that we don’t get enough DHA and EPA in the diet, but the other half of the equation is an excessive amount of Omega-6s.

The enzymes that convert the omega-3 fatty acids into pro-resolving enzymes are the same enzymes that convert some of the omega-6 fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid, into pro-inflammatory lipids. For example, ALOX12 is essential in the conversion of DHA into maresin 1 (pro-resolving mediator), but it is also part of how arachidonic acid is converted into 12-HETE, which is a pro-inflammatory and is involved in inflammation and immune cell recruitment.[ref]

Thus, the type of fat you eat (omega-6 oils vs. omega-3) interacts with your ability to convert the lipids into both pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators.

Aspirin and the conversion of SPMs

Willowbark, which contains salicylic acid (the active ingredient in aspirin), has been used to stop inflammation since at least 4,000 BCE.[ref] It turns out that aspirin, though, doesn’t just stop inflammation by blocking the formation of inflammatory prostanoids. It also helps to form pro-resolving mediators.

In addition to the enzymes above, the COX2 enzyme is involved in converting the resolvins and lipoxin in a special way that involves aspirin. Aspirin is a COX-1 inhibitor at lower levels, and at higher levels, it also changes the enzyme function of COX-2 via acetylation.[ref]

Aspirin is unique among NSAIDs in that it acetylates COX2, which then triggers the formation of ‘aspirin-triggered specialized pro-resolving mediators‘ or AT-SPMs. These aspirin-triggered SPMs include AT-lipoxin A4, AT-resolvin D1, and AT-resolvin D3.[ref][ref] Aspirin-triggered SPMs have a prolonged half-life and act to resolve inflammation for longer.[ref] This is likely why aspirin, and not other NSAIDs, helps to prevent heart disease and reduces the risk of colon cancer (for some people).

Very recently, researchers discovered that an endogenous compound can also act to form the so-called aspirin-induced SPMs. “In addition to aspirin, N-acetyl sphingosine (N-AS), generated from acetyl-CoA and sphingosine via sphingosine kinase1 (SphK1), also acetylates COX2 and increases RvE1 and 17R-RvD1.”[ref]

Receptors for SPMs:

Pro-resolving lipid mediators resolve inflammation by binding to a cellular receptor and causing an action to take place. Some of the actions triggered include: blocking inflammatory cytokines, converting macrophages to anti-inflammatory, promoting stem cells for tissue regeneration, and cleaning up cellular debris.

The cell types receiving the SPM pro-resolution signals via these receptors include platelets, macrophages, eosinophils, dendritic cells, epithelial cells (skin, intestinal cells), regulatory T cells, neutrophils, mast cells, and endothelial cells (lining of blood vessels).

Receptors for SPMs include:[ref]

- ALX (encoded by the FPR2 gene) is an RvD1 receptor. In mice, a lack of this receptor causes endothelial dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, and obesity.

- Protectin D1 activates GPR37 “Mice lacking Gpr37 display defects in macrophage phagocytic activity and delayed resolution of inflammatory pain”

- RvD5n-3 DPA was shown to bind to an orphan receptor GPR101 with high selectivity and stereospecificity.

- ERV1/ChemR23 is the receptor for several SPMs

- DRV1/GPR32

- DRV2/GPR18

- LGR6 (maresin 1 receptor on phagocytes)[ref]

The different SPMs bind with receptors on the cells to inhibit inflammation, stimulate the clearance of cellular debris, or promote tissue regeneration.

Let me give you some examples to illustrate how the different SPMs binding to receptors can cause a plethora of reactions that resolve inflammation as well as promote healing.

- Protectin D1 binds to receptors on neutrophils, inhibiting the release of TNF-alpha and interferon-gamma.[ref]

- Resolvin D2 binds to receptors on muscle stem cells and promotes an increase in muscle cell creation (important in muscular dystrophy).[ref]

- Pain is part of inflammation, and SPMs specifically target and reverse pain. Through inhibiting TRPV1, maresin R1 blocks neuropathic pain. Resolvin E1, resolvin D1, and aspirin-triggered resolvins reduce pain by knocking down TRPV3.[ref]

- The interaction of resolvin D1 with the FPR2 receptor causes an increase in PPARγ, which stops the migration of NF-ᴋB into the nucleus.[ref]

- In type 2 diabetes, it has been shown that upregulating the SPM receptors – especially the receptor for resolvin E1, potently regulates blood glucose levels.[ref]

- Resolvin D1 and D2 counteract histamine when it comes to watery eyes in allergic reactions. Resolvin D1 blocks histamine action via the H1 receptor (acted on by β-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 and protein kinase C phosphorylation).[ref]

- Resolvin D1, D2, and E1 prevent histamine-induced TRPV1 sensitisation. It may be important for stopping gut irritability in IBS.[ref]

- In periodontal disease, maresin R1 and resolvin E1 increase periodontal ligament stem cells, which regenerate lost tissue in gum disease.[ref]

Receptor agonist drugs:

In addition to natural SPMs binding to the receptors, pharmaceutical companies are working on drugs to promote these same pathways of the resolution of inflammation.[ref][ref][ref] Phase I clinical trials are underway.[ref]

Making connections: Chronic diseases and resolution of inflammation:

I want to tie together the resolution of inflammation with chronic diseases and genetics.

Most chronic diseases are due to a combination of genetic susceptibility, combined with diet/lifestyle/environmental factors. Click through to the related article to check your genetic susceptibility and then consider how SPMs also interact with your diet/lifestyle/environment.

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD):

In cardiovascular disease, ALOX5, an enzyme involved in SPM synthesis, was identified in an early genetics study. In addition to SPM synthesis in the presence of EPA, the ALOX5 enzyme can also synthesize inflammatory lipid mediators. The discovery that the gene was linked to CVD was the first signal that there was something wrong with resolving inflammation in heart disease. Currently, researchers point the finger squarely at the lack of resolution of inflammation as causal in heart disease. One recent study explains: “Atherosclerosis is a major human killer and non-resolving inflammation is a prime suspect” [ref]

Related article: Coronary Artery Disease: Genetic Susceptibility to Heart Disease

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease:

COPD includes inflammatory lung diseases such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis. The anti-inflammatory and resolution effects of lipoxin are very important in the lungs. In the lungs, lipoxin A4 triggers the migration of epithelial cells to repair injured bronchial tissue. Lipoxin B4 inhibits the migration of excess neutrophils into the area. Aspirin-triggered lipoxins also play a role in resolving inflammation in the lungs. Resolvin D1 is also important in lung immune system modulation and in the response to cigarette smoke. COPD patients generally have both lower levels of lipoxins and lower levels of the receptors for lipoxin in the lungs, which could cause the persistence of inflammation in the lungs via the lack of resolution.[ref]

Major Depressive Disorder:

A placebo-controlled clinical trial of multiple dosing levels of EPA and DHA showed a good response rate for major depressive disorder at high doses. The results showed that 4 g/d of EPA and 1.2 g of DHA for 12 weeks decreased inflammatory levels, increased pro-resolving mediators, and decreased depression. Importantly, the 1 to 2g/day of EPA/DHA wasn’t enough to make a difference compared to placebo.[ref][ref]

Related article: Depression, genetics, and inflammation

Chronic back pain:

Lower back pain is due to neuroinflammation. Animal models of herniated lumbar disc pain show that protectin D1 (from DHA) decreases inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and IL-6), facilitates healing, and attenuates the pain.[ref]

Related article: Back Pain and Genetics

Autoimmune diseases:

Reduced SPM levels are found in several types of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, Still’s disease, and Sjögren’s. Dysregulation in SPMs biosynthesis alters the adaptive immune response and may play a foundational role in autoimmune disease.[ref]

Related articles: Lupus and Sjögren’s

Arthritis:

From RA to osteoarthritis to gouty arthritis, inflammation is at the heart of this painful condition. Studies show that patients with arthritis have lower levels of specific SPMs, depending on the type and aggressiveness of the disease. Treatment with resolvin D1 or MaresinR1 acts as an analgesic for days to weeks. Supplementation with DHA and EPA also has some effectiveness in helping reduce inflammation in arthritis.[ref]

Related articles: Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

Multiple sclerosis:

SPM biosynthesis is impaired in people with multiple sclerosis, and low levels of SPMs correlate with disease progression in MS.[ref] This may be a key to the chronic inflammation involved in MS, which eventually causes demyelination of the neurons.

Related article: Multiple sclerosis and genetic variants

Inflammatory bowel disease:

Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis are caused by chronic intestinal inflammation. The lack of resolution of inflammation is thought to be a strong contributing factor: “…defective expression of pro-resolution mediators may contribute to the chronic inflammatory response associated with IBD. Notably, colonic mucosa from UC patients demonstrates defective LXA4 [lipoxin A4] biosynthesis, which may contribute to the inability of these patients to resolve persistent colonic inflammation.”[ref]

Related article: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Diabetes:

In type 2 diabetes, research shows that the BLT1 receptor for resolvin E1 is impaired. Interestingly, higher levels of resolvin E1 were able to overcome some of the inflammatory dysregulations.[ref]

Related article: Type 2 Diabetes Genes

Neuropathic pain:

Damage to the central nervous system can cause peripheral neuropathy, mechanical allodynia, MS, or other pain syndromes. While it makes sense that the resolution of inflammation would stop pain, researchers have discovered that the role of the SPMs may be more in-depth when it comes to neuropathic pain. Research points to the role of SPMs in both opioid receptors and TRP channels, which may signal to stop pain through the central nervous system.[ref]

Research on neuropathic pain and supplemental SPMs shows an array of positive results (mostly in animal studies). Lipoxin A4 reduces inflammatory hyperalgesia, inhibits NF-kB, and reduces IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. Resolvins blunt pain perception, downregulate NF-kB in the lower back, prevent inflammatory hypersensitivity, and act as an analgesic.

Getting a little more specific: Resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 can directly inhibit TRP channels on the surface of sensory neurons. TRPV1, TRPV3, TRPV4, and TRPA1 are inhibited by these resolvins, and this reduces sensitivity to heat-induced pain as well as agonist-induced pain. Additionally, maresin R1 acts on the TRPV receptors. These receptors are also activated by capsaicin in hot chili peppers.[ref]

Related article: TRPV1 receptor variants

Infections:

Sepsis is an out-of-control inflammatory reaction, usually in response to a bacterial infection. SPMs, in addition to all their anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving properties, also enhance the clearance of bacterial and viral pathogens while at the same time limiting collateral tissue damage.[ref]

Specialized pro-resolving mediators also play a role in host defense against viruses such as influenza A, RSV, and HIV. Clearance of bacterial pathogens also involves SPMs. For example, animal studies show that the absence of lipoxins in Lyme disease causes chronic disease symptoms such as joint pain.[ref]

Related articles: chronic Lyme disease

Atrial Fibrillation:

A-fib persistence increases inflammation through excessive ROS production in the endothelium. Researchers now think that resolvin D1 may inhibit the increase in inflammation.[ref]

Related article: Atrial fibrillation genes

Traumatic brain injury:

Resolving inflammation is very important in the brain after a concussion. A diet high in omega-3 and low in omega-6 has been shown to reduce headaches after traumatic brain injury. Animal studies show that resolvin D1 is the key SPM involved in healing brain injury.[ref][ref]

Cancer: Inflammation and SPMs

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Conclusion:

Targeting the resolution of inflammation rather than just blocking the formation of proinflammatory cytokines is likely to help prevent and reverse chronic diseases.

While this whole article has focused on the resolution of inflammation, the other half of the picture is to stop the source of inflammation.

Modern sources of inflammation include cigarette smoke, air pollution exposure, a crappy diet, poor sleep, chronic infections (e.g., gum disease), or stress.

Your source of chronic inflammation is likely not the same as mine.

Not everyone reacts to inflammatory substances in the same way. One person may be able to eliminate a little arsenic with no problem, but they may not be able to handle organophosphate pesticides.

Start by looking at your genetic variants that increase inflammatory cytokines. Also, look at your detoxification genetic variants. If you see a lot of risk alleles highlighted, go and read the article. For example, some people should be careful to avoid BPA or phthalates, while others should focus on certain pesticides. Arsenic in your well water may be a problem when combined with certain genetic variants. If air quality is poor in your area, an indoor air filtration system may be a good investment.

Consider ways to limit inflammatory conditions in the body, and then couple that with ways to boost the resolution of inflammation.

Related Articles and Topics:

TNF-alpha: Inflammation, Chronic Diseases, and Genetic Susceptibility

Underlying Cause(s) of Depression: Leveraging Your Genetic Data

References:

Albuquerque-Souza, Emmanuel, et al. “Maresin-1 and Resolvin E1 Promote Regenerative Properties of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells Under Inflammatory Conditions.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 11, 2020, p. 585530. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.585530.

AlSaleh, Aseel, et al. “Genetic Predisposition Scores for Dyslipidaemia Influence Plasma Lipid Concentrations at Baseline, but Not the Changes after Controlled Intake of n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids.” Genes & Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 4, July 2014, p. 412. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-014-0412-8.

Asahina, Yoshikazu, et al. “Discovery of BMS-986235/LAR-1219: A Potent Formyl Peptide Receptor 2 (FPR2) Selective Agonist for the Prevention of Heart Failure.” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 63, no. 17, Sept. 2020, pp. 9003–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02101.

Basil, Maria C., and Bruce D. Levy. “Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators: Endogenous Regulators of Infection and Inflammation.” Nature Reviews Immunology, vol. 16, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 51–67. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2015.4.

Bokor, Szilvia, et al. “Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the FADS Gene Cluster Are Associated with Delta-5 and Delta-6 Desaturase Activities Estimated by Serum Fatty Acid Ratios.” Journal of Lipid Research, vol. 51, no. 8, Aug. 2010, pp. 2325–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M006205.

Botting, Regina. “COX-1 and COX-3 Inhibitors.” Thrombosis Research, vol. 110, no. 5–6, June 2003, pp. 269–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00411-0.

Cezar, Talita L. C., et al. “Treatment with Maresin 1, a Docosahexaenoic Acid-Derived pro-Resolution Lipid, Protects Skin from Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Caused by UVB Irradiation.” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, 2019. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39584-6.

Chiang, Nan, and Charles N. Serhan. “Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediator Network: An Update on Production and Actions.” Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 64, no. 3, Sept. 2020, p. 443. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20200018.

Chronic Diseases in America | CDC. 27 Jan. 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm.

Ciaccia, Laura. “Fundamentals of Inflammation.” The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, vol. 84, no. 1, Mar. 2011, pp. 64–65. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3064252/.

Colas, Romain A., et al. “Impaired Production and Diurnal Regulation of Vascular RvDn-3 DPA Increases Systemic Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease.” Circulation Research, vol. 122, no. 6, Mar. 2018, p. 855. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312472.

Dort, Junio, et al. “Resolvin-D2 Targets Myogenic Cells and Improves Muscle Regeneration in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, Oct. 2021, p. 6264. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26516-0.

Elajami, Tarec K., et al. “Specialized Proresolving Lipid Mediators in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Their Potential for Clot Remodeling.” The FASEB Journal, vol. 30, no. 8, Aug. 2016, p. 2792. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201500155R.

Fishbein, Anna, et al. “Carcinogenesis: Failure of Resolution of Inflammation?” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 218, Feb. 2021, p. 107670. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107670.

Fredman, Gabrielle, and Katherine C. MacNamara. “Atherosclerosis Is a Major Human Killer and Non-Resolving Inflammation Is a Prime Suspect.” Cardiovascular Research, vol. 117, no. 13, Nov. 2021, p. 2563. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvab309.

Fredman, Gabrielle, and Ira Tabas. “Boosting Inflammation Resolution in Atherosclerosis: The Next Frontier for Therapy.” The American Journal of Pathology, vol. 187, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 1211–21. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.01.018.

Freire, Marcelo O., et al. “Neutrophil Resolvin E1 Receptor Expression and Function in Type 2 Diabetes.” Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), vol. 198, no. 2, Jan. 2017, pp. 718–28. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1601543.

Gilligan, Molly M., et al. “Aspirin-Triggered Proresolving Mediators Stimulate Resolution in Cancer.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 116, no. 13, Mar. 2019, pp. 6292–97. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804000116.

Hansen, Trond Vidar, et al. “The Protectin Family of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators: Potent Immunoresolvents Enabling Innovative Approaches to Target Obesity and Diabetes.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 9, 2019. Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2018.01582.

Kantarci, Alpdogan, et al. “Combined Administration of Resolvin E1 and Lipoxin A4 Resolves Inflammation in a Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Experimental Neurology, vol. 300, Feb. 2018, pp. 111–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.11.005.

Kooij, Gijs, et al. “Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Are Differentially Altered in Peripheral Blood of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Attenuate Monocyte and Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction.” Haematologica, vol. 105, no. 8, Aug. 2020, pp. 2056–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.219519.

Kotlyarov, Stanislav, and Anna Kotlyarova. “Anti-Inflammatory Function of Fatty Acids and Involvement of Their Metabolites in the Resolution of Inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 23, Dec. 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312803.

Kwan, Cheuk-Kin, et al. “A High Glucose Level Stimulate Inflammation and Weaken Pro-Resolving Response in Tendon Cells – A Possible Factor Contributing to Tendinopathy in Diabetic Patients.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation and Technology, vol. 19, Jan. 2020, pp. 1–6. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2019.10.002.

Leuti, Alessandro, et al. “Role of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Neuropathic Pain.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 12, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.717993.

Levy, Bruce D., et al. “Protectin D1 Is Generated in Asthma and Dampens Airway Inflammation and Hyperresponsiveness.” Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), vol. 178, no. 1, Jan. 2007, pp. 496–502. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.496.

Livne-Bar, Izhar, et al. “Astrocyte-Derived Lipoxins A4 and B4 Promote Neuroprotection from Acute and Chronic Injury.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 127, no. 12, pp. 4403–14. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI77398. Accessed 2 Mar. 2022.

Mansara, Prakash P., et al. “Differential Ratios of Omega Fatty Acids (AA/EPA+DHA) Modulate Growth, Lipid Peroxidation and Expression of Tumor Regulatory MARBPs in Breast Cancer Cell Lines MCF7 and MDA-MB-231.” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 9, 2015. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136542.

Mizraji, Gabriel, et al. “Resolvin D2 Restrains Th1 Immunity and Prevents Alveolar Bone Loss in Murine Periodontitis.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 9, Apr. 2018, p. 785. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00785.

Molaei, Emad, et al. “Resolvin D1, Therapeutic Target in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.” European Journal of Pharmacology, vol. 911, Nov. 2021, p. 174527. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174527.

Panigrahy, Dipak, et al. “Preoperative Stimulation of Resolution and Inflammation Blockade Eradicates Micrometastases.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 129, no. 7, June 2019, p. 2964. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI127282.

Perna, Eluisa, et al. “Effect of Resolvins on Sensitisation of TRPV1 and Visceral Hypersensitivity in IBS.” Gut, vol. 70, no. 7, July 2021, pp. 1275–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321530.

Serhan, Charles N. “Discovery of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators Marks the Dawn of Resolution Physiology and Pharmacology.” Molecular Aspects of Medicine, vol. 58, Dec. 2017, p. 1. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2017.03.001.

Serhan, Charles N., Nan Chiang, et al. “Lipid Mediators in the Resolution of Inflammation.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 7, no. 2, Feb. 2015, p. a016311. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a016311.

Serhan, Charles N., Jesmond Dalli, et al. “Protectins and Maresins: New Pro-Resolving Families of Mediators in Acute Inflammation and Resolution Bioactive Metabolome.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, vol. 1851, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. 397–413. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.006.

Shan, Kai, et al. “Resolvin D1 and D2 Inhibit Tumour Growth and Inflammation via Modulating Macrophage Polarization.” Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, vol. 24, no. 14, July 2020, pp. 8045–56. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.15436.

Sima, Corneliu, et al. “Function of Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediator Resolvin E1 in Type 2 Diabetes.” Critical Reviews in Immunology, vol. 38, no. 5, 2018, pp. 343–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2018026750.

Stalder, Anna K., et al. “Biomarker-Guided Clinical Development of the First-in-Class Anti-Inflammatory FPR2/ALX Agonist ACT-389949.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 83, no. 3, Mar. 2017, pp. 476–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13149.

Sugimoto, Michelle A., et al. “Resolution of Inflammation: What Controls Its Onset?” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 7, 2016. Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00160.

Szczuko, Małgorzata, et al. “Lipoxins, RevD1 and 9, 13 HODE as the Most Important Derivatives after an Early Incident of Ischemic Stroke.” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, July 2020, p. 12849. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69831-0.

Trojan, Ewa, et al. “The N-Formyl Peptide Receptor 2 (FPR2) Agonist MR-39 Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Activity in LPS-Stimulated Organotypic Hippocampal Cultures.” Cells, vol. 10, no. 6, June 2021, p. 1524. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10061524.

Wang, C. W., et al. “Maresin 1 Promotes Wound Healing and Socket Bone Regeneration for Alveolar Ridge Preservation.” Journal of Dental Research, vol. 99, no. 8, July 2020, pp. 930–37. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520917903.

Xia, Haifa, et al. “Protectin DX Increases Survival in a Mouse Model of Sepsis by Ameliorating Inflammation and Modulating Macrophage Phenotype.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, Mar. 2017, p. 99. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00103-0.

Yang, Menglu, et al. “Resolvin D2 and Resolvin D1 Differentially Activate Protein Kinases to Counter-Regulate Histamine-Induced [Ca2+]i Increase and Mucin Secretion in Conjunctival Goblet Cells.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2021, p. 141. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010141.

Yarmohammadi, Fatemeh, et al. “Possible Protective Effect of Resolvin D1 on Inflammation in Atrial Fibrillation: Involvement of ER Stress Mediated the NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway.” Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, vol. 394, no. 8, Aug. 2021, pp. 1613–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-021-02115-0.

Zhao, Qing-xiang, et al. “Protectin DX Attenuates Lumbar Radicular Pain of Non-Compressive Disc Herniation by Autophagy Flux Stimulation via Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 12, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.784653.

Zhao, Yuhai, et al. “Docosahexaenoic Acid-Derived Neuroprotectin D1 Induces Neuronal Survival via Secretase- and PPARγ-Mediated Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease Models.” PLOS ONE, vol. 6, no. 1, Jan. 2011, p. e15816. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015816.

https://academic.oup.com/HTTPHandlers/Sigma/LoginHandler.ashx?error=login_required&state=178926e4-6e35-4c5a-8944-5566db5f3171redirecturl%3Dhttpszazjzjacademiczwoupzwcomzjjnzjarticlezj141zj7zj1247zj4743365. Accessed 2 Mar. 2022.