Key takeaways:

~ Tyramine can build up and result in serious difficulties like heart palpitations, spiking blood pressure, stroke-like symptoms, nausea, gastrointestinal issues, migraines, and brain fog.

~ Genetic variants in three key pathways impact how well you break down and eliminate tyramine.

~ Medications, especially MAOIs, also impact tyramine metabolism.

What is tyramine intolerance? Symptoms, foods, and metabolism

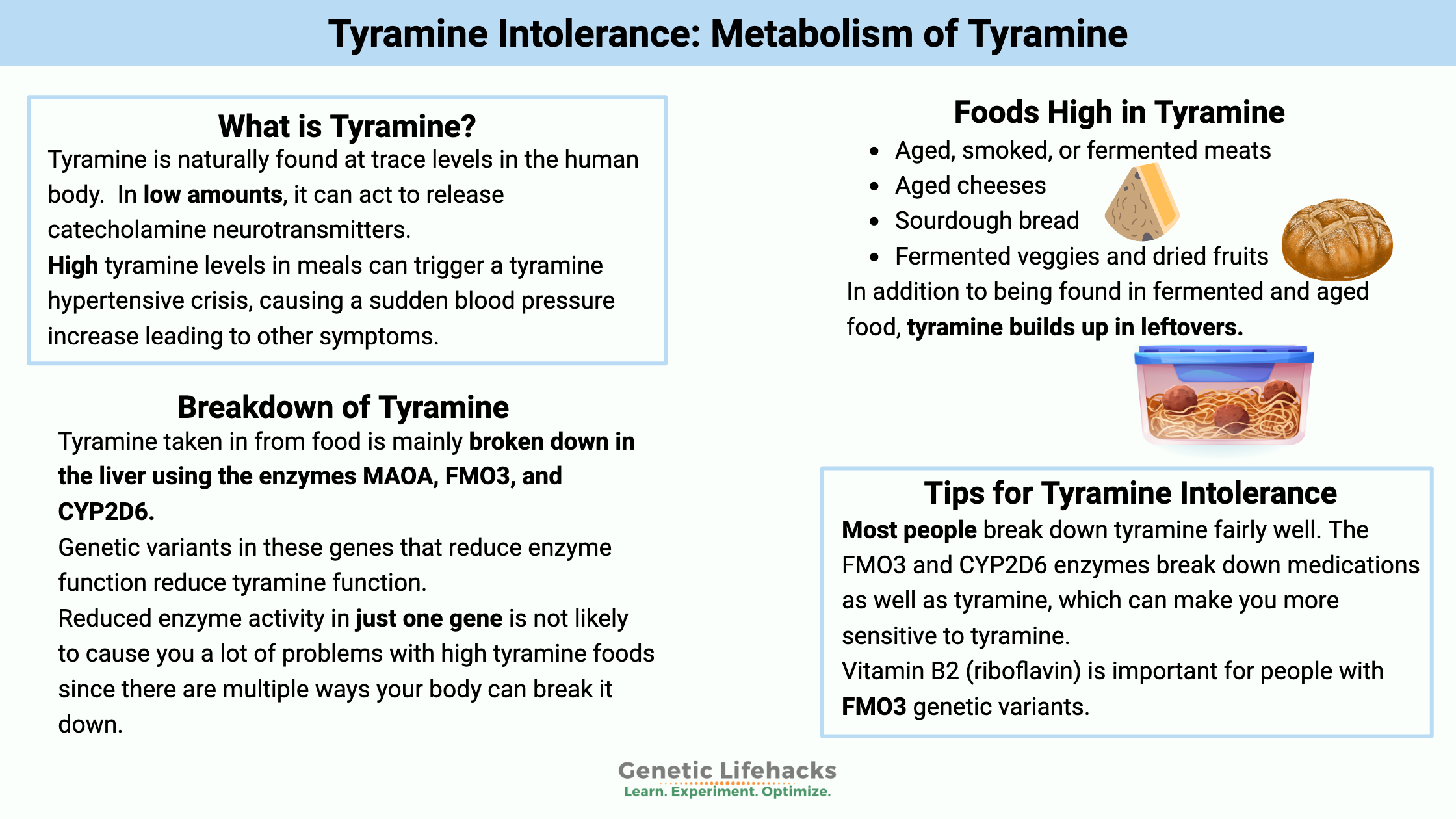

High tyramine levels in meals can trigger a tyramine hypertensive crisis, commonly known as the ‘cheese effect.’ This is usually associated with taking an MAO inhibitor, and people on an MAOI are cautioned by their doctor about the dietary interactions.

The hypertensive crisis is caused by too much tyramine, causing a sudden blood pressure increase leading to other symptoms.

I’ll start with some background on tyramine and then explain the genetic implications.

What is tyramine?

Tyramine is a biogenic amine, which refers to its chemical structure with nitrogen at its base. It is naturally found at trace levels in the human body.

Histamine, spermidine, dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, and norepinephrine are all amines that we create naturally. Neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, adrenaline, and norepinephrine, as well as histamine, are known to cause allergic reactions.

Tyramine, in low amounts, can act to release catecholamine neurotransmitters. It can cross the blood-brain barrier and act as a neuromodulator in the brain.

Tyramine can also be found in foods – especially fermented foods or foods close to spoiling. This is where the ‘cheese effect‘ comes into play. (Read the background on how it was discovered as a reaction in people on MOAI drugs)

Which foods are high in tyramine?

A quick list of foods high in tyramine include:

- Aged, smoked, or fermented meats (salami, pepperoni, cured sausages, bacon, corned beef, beef jerky, etc.)

- Aged cheeses (cheddar, gouda, Swiss, parmesan, feta, Brie, etc.)

- Sourdough bread and some homemade yeast bread

- Marmite and other yeasty things

- Fermented veggies and dried fruits (sauerkraut, kimchi, tofu, soy sauce)

- Some beers and wines (especially unpasteurized beer such as homemade or tap)

- Medium sources include: olives, chocolate, snow peas, edamame, avocados, bananas, pineapple, eggplant, figs, yogurt, sour cream, peanuts, Brazil nuts, fava beans (broad beans)

Many foods that are high in tyramine are also high in histamine. You may find it difficult to know whether you’re reacting to histamine or tyramine in foods. Read this histamine intolerance article to learn about genetic susceptibility and symptom differences.

How does the body get rid of tyramine?

Tyramine is absorbed in the intestines from foods. Additionally, certain gut microbes can produce tyramine from tyrosine.

Tyramine is mainly broken down (metabolized) in the body using these three enzymes:

- MAO-A (monamine oxidase A)

- FMO3 (flavin-containing monooxygenase 3)

- CYP2D6 (a CYP450 family detoxification enzyme)

MAO-A is the enzyme that metabolizes several neurotransmitters, including dopamine.

Inhibiting or decreasing MAO-A is one way to increase dopamine levels. Thus, drugs that act as MAO-A inhibitors (MAOIs) can be used as antidepressants, although they usually aren’t the first choice due to the dietary interactions with tyramine.

Once tyramine is metabolized, utilizing one of the enzymes above in the reaction, it is eliminated from the body in the urine.[ref]

Tyramine reactions:

If you get too much tyramine due to eating foods high in tyramine and not breaking down the tyramine (e.g., when taking an MAO-A inhibitor), it can throw your body into a hypertensive crisis, raising systolic blood pressure by 30 mmHg or more.

This is called the ‘tyramine pressor response’.

Tyramine takes the place of other neurotransmitters, triggering the body to release a bunch of norepinephrine, constricting blood vessels and raising blood pressure.[ref]

Interestingly, some of the first studies on the pressor effect of raising blood pressure were done in the early 1900s using rotting horse meat.[ref]

You may wonder why we all aren’t dropping dead from a heart attack after eating a salami and cheese sandwich on sourdough bread…

There are a couple of reasons for this:

- First, most people break down tyramine fairly well. There are three different enzyme pathways to take care of it.

- Second, repeated exposure to tyramine will decrease the tyramine pressor response. The change from typically not eating foods high in tyramine to suddenly chowing down on them can cause a response. For instance, eating a healthy diet full of fresh foods — and then hitting the holiday buffet and having salami, cheese, and olives, chased with a glass of red wine.

Tyramine Sensitivity and Migraines

For people susceptible to migraines, the list of foods high in tyramine may correspond to your list of ‘triggers’.

- Many people with either cluster headaches or migraines don’t break down tyramine well.[ref]

- Researchers think that vasoconstriction triggered by tyramines initiates migraines.[ref][ref]

Fun fact:

Tyramine is chemically similar to amphetamine and methamphetamine, although it doesn’t produce the same effects. The state of Florida banned tyramine as a Schedule I drug in 2012.[ref]

Does this mean that selling chocolate and cheese is a felony in Florida?

Tyramine Metabolism Genotype Report

Lifehacks: Natural solutions for tyramine

Riboflavin for tyramine intolerance:

Related Articles and Topics:

Histamine Intolerance

Excess histamine can cause allergy-type reactions in some people.

Serotonin

Your genes play a role in how much serotonin is made, how it is broken down, and how cells receive the serotonin signal.

Your need for riboflavin (B2): MTHFR and other genetic variants

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) is a water-soluble vitamin that is a cofactor for many enzymes in the body.

Detoxification: Phase I and Phase II Metabolism

Our body has an amazing capacity to rid itself of harmful substances. We take in toxins daily by eating natural plant toxins. We are exposed to toxicants (man-made toxins) through pesticide residue, air pollution, skincare products, and medications.

Trimethylaminuria: Genetic variants that cause a malodorous body odor

Often referred to as ‘fish odor disease’, trimethylaminuria causes a strong odor in sweat, urine, and breath. It is caused by mutations in the FMO3 gene.

References:

“Avoid the Combination of High-Tyramine Foods and MAOIs.” Mayo Clinic, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/expert-answers/maois/faq-20058035. Accessed 16 Nov. 2022.

Barger, G., and G. S. Walpole. “Isolation of the Pressor Principles of Putrid Meat.” The Journal of Physiology, vol. 38, no. 4, Mar. 1909, pp. 343–52. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1533642/.

Bushueva, Olga, et al. “The Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 Gene and Essential Hypertension: The Joint Effect of Polymorphism E158K and Cigarette Smoking on Disease Susceptibility.” International Journal of Hypertension, vol. 2014, Aug. 2014, p. e712169. www.hindawi.com, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/712169.

Cronometer: Eat Smarter. Live Better. https://cronometer.com/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2022.

D’Andrea, G., et al. “Biochemistry of Neuromodulation in Primary Headaches: Focus on Anomalies of Tyrosine Metabolism.” Neurological Sciences, vol. 28, no. 2, May 2007, pp. S94–96. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-007-0758-4.

Hotamisligil, G. S., and X. O. Breakefield. “Human Monoamine Oxidase A Gene Determines Levels of Enzyme Activity.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 49, no. 2, Aug. 1991, pp. 383–92.

How a Migraine Happens. 26 Nov. 2019, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/headache/how-a-migraine-happens.

Kashyap, A. S., and Surekha Kashyap. “Fish Odour Syndrome.” Postgraduate Medical Journal, vol. 76, no. 895, May 2000, pp. 318–318. pmj.bmj.com, https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.76.895.318a.

Koukouritaki, Sevasti B., et al. “Discovery of Novel Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Functional Analysis of Upstream Haplotype Variants.” Molecular Pharmacology, vol. 68, no. 2, Aug. 2005, pp. 383–92. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.105.012062.

Manning, Nigel J., et al. “Riboflavin-Responsive Trimethylaminuria in a Patient with Homocystinuria on Betaine Therapy.” JIMD Reports, vol. 5, 2012, pp. 71–75. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/8904_2011_99.

Niwa, Toshiro, et al. “Human Liver Enzymes Responsible for Metabolic Elimination of Tyramine; a Vasopressor Agent from Daily Food.” Drug Metabolism Letters, vol. 5, no. 3, Aug. 2011, pp. 216–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/187231211796905026.

NM_006894.5(FMO3):C.913G>T (p.Glu305Ter) AND Trimethylaminuria – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000017697.30/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2022.

NM_001002294.3(FMO3):C.589_590TG[1] (p.Cys197_Asp198delinsTer) AND Trimethylaminuria – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000490504.1/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2022.

Rafehi, Muhammad, et al. “Highly Variable Pharmacokinetics of Tyramine in Humans and Polymorphisms in OCT1, CYP2D6, and MAO-A.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 10, Oct. 2019, p. 1297. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01297.

Sathyanarayana Rao, T. S., and Vikram K. Yeragani. “Hypertensive Crisis and Cheese.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 51, no. 1, 2009, pp. 65–66. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.44910.

tammy-lrome. “Low-Tyramine Diet Essentials.” Migraine.Com, https://migraine.com/blog/low-tyramine-diet-essentials. Accessed 16 Nov. 2022.

Walker, S. E., et al. “Tyramine Content of Previously Restricted Foods in Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor Diets.” Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, vol. 16, no. 5, Oct. 1996, pp. 383–88. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/00004714-199610000-00007.

Xu, Meijuan, et al. “Genetic and Nongenetic Factors Associated with Protein Abundance of Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 in Human Liver.” The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, vol. 363, no. 2, Nov. 2017, pp. 265–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.117.243113.

Xu, Xiaohui, et al. “Association Study between the Monoamine Oxidase A Gene and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Taiwanese Samples.” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 7, Feb. 2007, p. 10. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-7-10.

Zubiaur, Pablo, et al. “SLCO1B1 Phenotype and CYP3A5 Polymorphism Significantly Affect Atorvastatin Bioavailability.” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 11, no. 3, Mar. 2021, p. 204. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11030204.