Key takeaways:

~Once thought to be a rare genetic disease, new research shows that hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) may be more common, especially in people of African ancestry.

~Several new drugs are in clinical trials for hATTR.

~Understanding your genetic risk can help you seek treatment earlier before the damage is irreversible.

What does the TTR protein do?

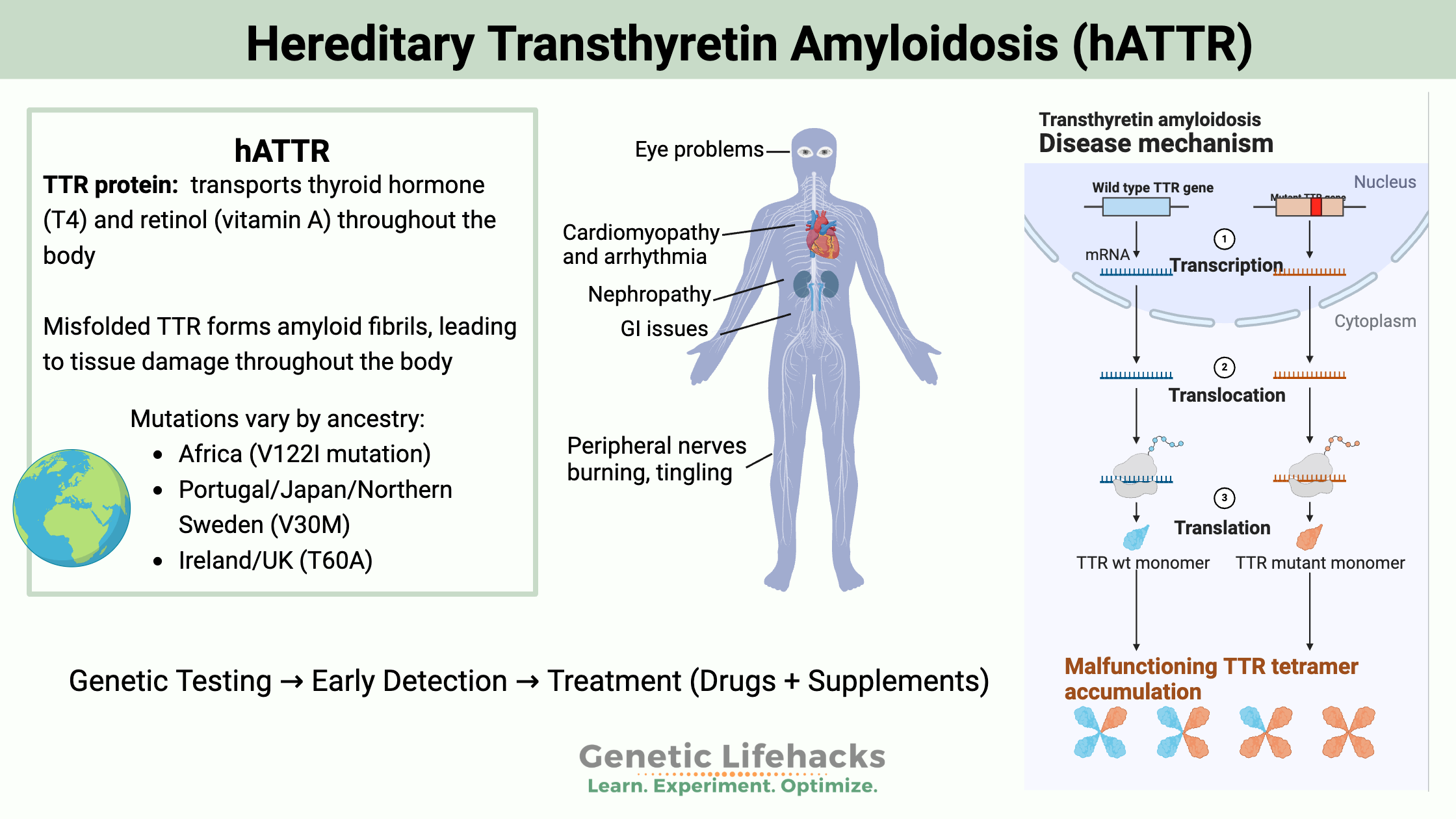

The transthyretin (TTR) protein transports both thyroid hormone (T4, thyroxine) and retinol (a form of vitamin A) to the liver.

The protein is named transthyretin because it transports thyroxine (thyroid hormone) and retinol (vitamin A).

The TTR protein is made in the liver and in the choroid plexus, which is the region where cerebrospinal fluid is produced. It circulates through the bloodstream and the cerebrospinal fluid.

The thyroid secretes several different thyroid hormones. T4, or thyroxine, circulates bound to a protein. T4 is either bound to thyroid hormone-binding protein – or – bound to TTR.

Retinol, or vitamin A, is important in many biological functions, including regulating cell differentiation, neuron growth, and neuron survival. Retinol is transported in the bloodstream bound to retinol-binding protein and TTR. These two proteins together form a stable complex that keeps vitamin A from being broken down and excreted.[ref]

As you can see, the TTR protein has a couple of essential functions in the body. Unfortunately, the TTR protein can also cause significant problems for a few people…

What is hATTR polyneuropathy?

Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) is a genetic disease caused by mutations in the transthyretin (TTR) gene. These changes can impact the peripheral and autonomic nervous systems, as well as the cardiovascular system.

hATTR was formerly referred to as Transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP) or transthyretin familial amyloid cardiomyopathy.

Extracellular deposition of the misfolded proteins (amyloids) causes hATTR symptoms.

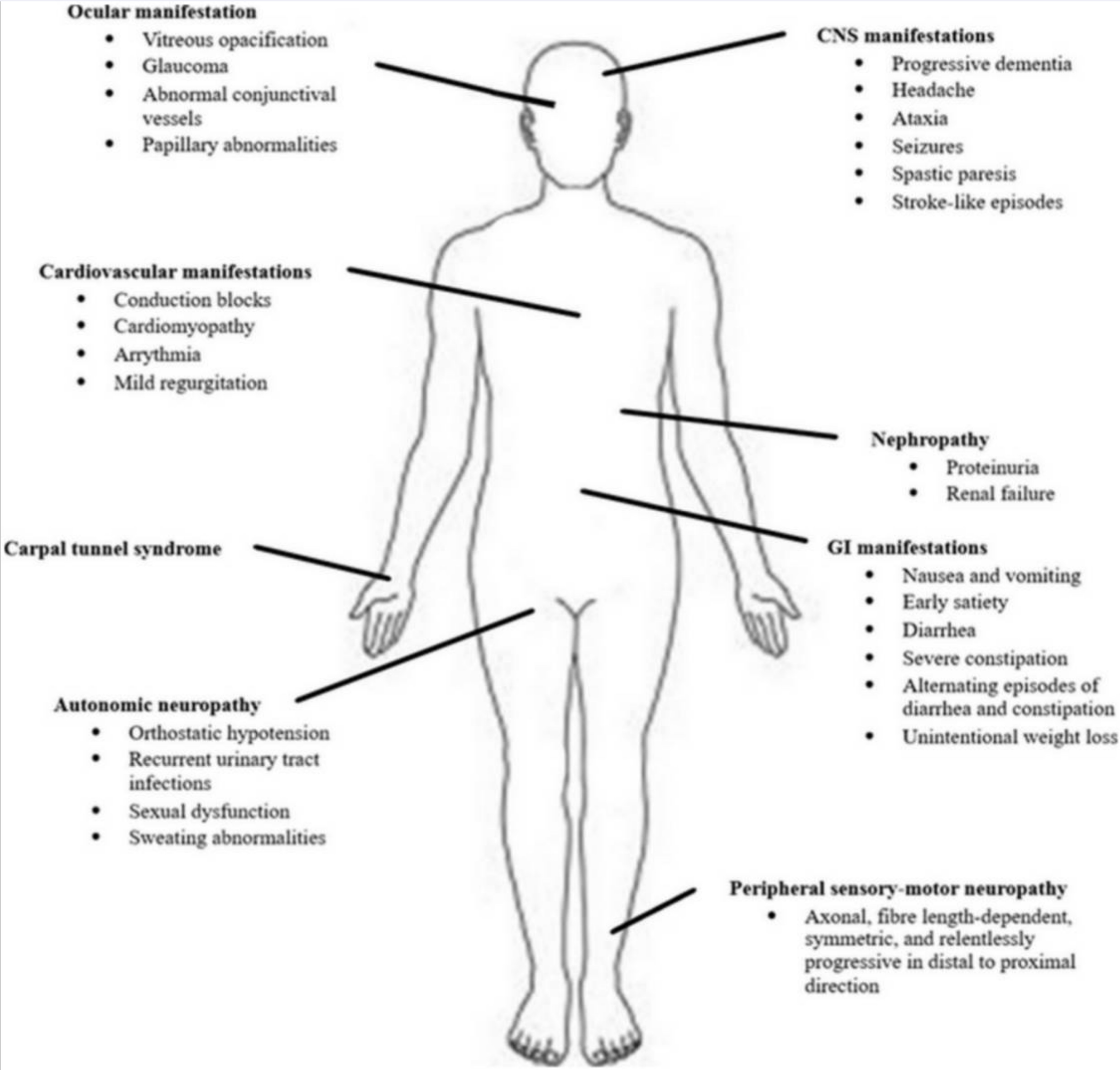

The misfolded TTR proteins combine to form amyloid fibrils, causing cytotoxicity and tissue damage. The deposition of the amyloid fibrils in various tissues (nerve, heart, eyes, kidney, gastrointestinal mucosa) causes cellular damage and the subsequent symptoms of hATTR.

Quick terminology time-out:

Amyloid is a general term applied to misfolded proteins that create a certain type of structural change. The overarching term for diseases caused by amyloids is amyloidosis. There are about three dozen different amyloidosis diseases, each due to a different protein that misfolds and causes fibrils to form. The most well-known is amyloid-beta (misfolded APP protein) which is implicated in causing Alzheimer’s disease.[ref]

TTR polyneuropathy symptoms often begin before age 50.

hATTR symptoms include:

- paresthesia (pins and needles or numbness in the skin)

- burning sensations or numbness, usually starting in the feet

- dysautonomic nervous system problems (bowel issues, impotence,

- dysesthesia (weird, unpleasant touch sensations, kind of like pain)

hATTR CM – Heart Symptoms and other symptoms

TTR cardiac symptoms can include cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia.[ref]

Other symptoms can include problems in the eyes, and kidneys, carpal tunnel syndrome, and gastrointestinal issues.

What causes hATTR?

Mutations in the TTR gene cause the hereditary form of TTR amyloidosis. Currently, over 120 known mutations in the gene are linked to hATTR. Some mutations are more likely to result in heart issues, while others usually present with nerve problems first.[ref]

Certain mutations are more commonly found in ancestry groups and locations:

- rs76992529, or VI122I, is most common in African Americans and people of West African descent

- rs28933979, or V30M, is most common in people of Portuguese, Northern Swedish, and Japanese descent

- rs121918070, or T60A, is most common in people of Irish and British descent.

- rs267607161, or A117S, is found in Chinese Malaysians.[ref]

In addition to the hereditary form of amyloid TTR, some people without mutations in the gene can also end up with proteins that misfold and aggregate. It is known as wild-type ATTR or wild-type transthyretin amyloid and mainly affects the heart. Wild-type ATTR is more likely in the elderly.

TTR Genotype Report:

Lifehacks:

If your genetic data shows a TTR mutation, talk with your doctor about testing to confirm.

Your doctor can also help with medications in clinical trials or recently approved for hATTR. You can read more about pharmaceutical treatments here: https://www.hattrguide.com/hattr-amyloidosis-treatment/

Supplement research for hATTR:

Several natural supplements may also interact with the TTR gene.

Related Articles and Topics:

Luteolin Benefits: Anti-inflammatory and Neuroprotective

New research suggests the benefits of luteolin (a flavonoid found in fruits, vegetables, and herbs) may include anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties.

Small Fiber Neuropathy: Genetics, Causes, and Possible Solutions

Small Fiber Neuropathy (SFN) results in burning pain, numbness, odd sensations, or autonomic nervous system issues. Learn more about the possible causes and potential solutions to this debilitating disorder.

NLRP3 Inflammasome, Genetics, and Chronic Inflammation

What makes people more susceptible to chronic inflammatory diseases? The root of the over-activation of inflammation for some people could be the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Serotonin 2A receptor variants: psychedelics, brain aging, and Alzheimer’s disease

Learn how new research on brain aging and dementia connects the serotonin 2A receptor with psychedelics, brain aging, and Alzheimer’s.

References:

Amyloidosis: Definition of Amyloid and Amyloidosis, Classification Systems, Systemic Amyloidoses. June 2022. eMedicine, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/335414-overview.

Bemporad, Francesco, et al. “The Transthyretin/Oleuropein Aglycone Complex: A New Tool against TTR Amyloidosis.” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 15, no. 3, Feb. 2022, p. 277. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15030277.

Ferreira, Nelson, et al. “Curcumin: A Multi-Target Disease-Modifying Agent for Late-Stage Transthyretin Amyloidosis.” Scientific Reports, vol. 6, May 2016, p. 26623. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26623.

Liu, Yo‐Tsen, et al. “Biophysical Characterization and Modulation of Transthyretin Ala97Ser.” Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, vol. 6, no. 10, Sept. 2019, pp. 1961–70. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.50887.

Low, Soon Chai, et al. “Ala97Ser Mutation Is Common among Ethnic Chinese Malaysians with Transthyretin Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy.” Amyloid: The International Journal of Experimental and Clinical Investigation: The Official Journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis, vol. 26, no. sup1, 2019, pp. 7–8. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/13506129.2019.1582479.

Luigetti, Marco, et al. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (HATTR) Polyneuropathy: Current Perspectives on Improving Patient Care.” Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, vol. 16, Feb. 2020, pp. 109–23. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S219979.

Vieira, Marta, and Maria João Saraiva. “Transthyretin: A Multifaceted Protein.” BioMolecular Concepts, vol. 5, no. 1, Mar. 2014, pp. 45–54. www.degruyter.com, https://doi.org/10.1515/bmc-2013-0038.