Key Takeaway:

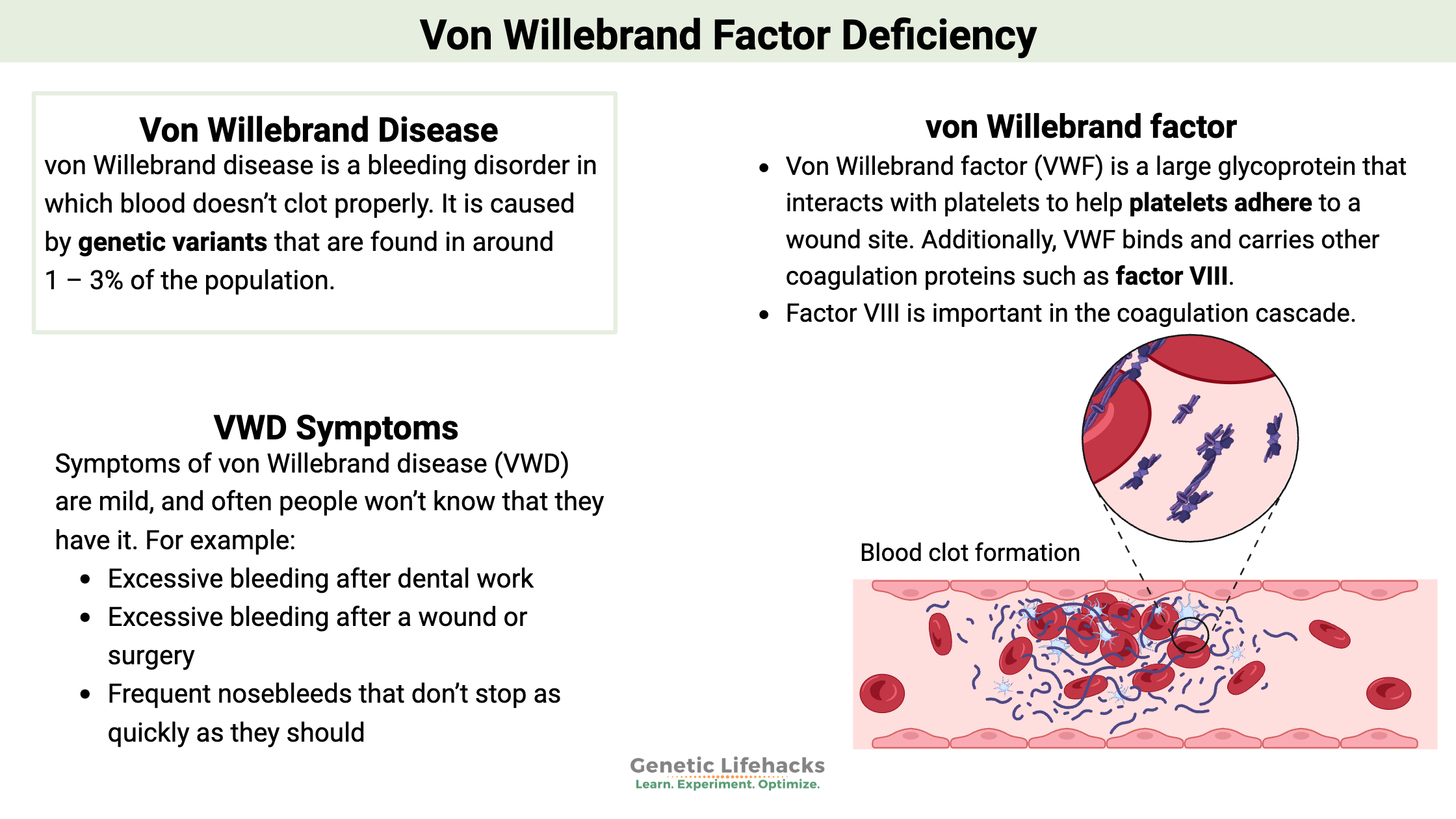

~ von Willebrand disease is a bleeding disorder in which blood doesn’t clot properly.

~ It is due to genetic mutations that cause the von Willebrand factor not to perform as it should.

~ Genetic variants in the VWF gene can cause easy bleeding due to decreased clotting.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Von Willebrand disease:

Symptoms of von Willebrand disease (VWD) are mild, and often people won’t know that they have it. The most commonly noted symptom is abnormal bleeding. For example:

- Excessive bleeding after dental work

- Excessive bleeding after a wound or surgery

- Frequent nosebleeds that don’t stop as quickly as they should

- Heavy or long menstrual bleeding

- Heavy bleeding when having a baby

- Easy bruising, such as bruises when you don’t remember getting injured

Let’s dive into a few of the details as to why a lack of von Willebrand factor causes easy bleeding (or decreased clotting).

Background: Platelets and clotting

When you get a cut, platelets are an integral part of the body’s clotting system. Platelets jump into the break of tissue and release a bunch of different clotting factors, helping to bind to the site of the wound and create a clot to stop the blood flow.

Platelets also activate other coagulation factors. Essentially, they interact with the endothelial cells lining our blood vessels, attaching to cut endothelial cells or any abnormality on the blood vessel cell wall.

Here is an overview showing the injury to the blood vessel (A), the recruitment and activation of platelets (B and C), the aggregation of the platelets (D), and then a plug forming to stop blood loss.[ref]

What does von Willebrand factor do?

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a large glycoprotein that interacts with platelets to help platelets adhere to a wound site. Additionally, VWF binds and carries other coagulation proteins such as factor VIII.[ref]

Factor VIII is important in the coagulation cascade. When there is no need for clot formation, factor VIII is carried by VWF and is inactive. When thrombin is present (in the formation process of a clot), factor VIII is released by VWF.

When a blood vessel is damaged, collagen is exposed beneath the endothelial cells. von Willebrand factor binds to the collagen – and then also binds to platelets, essentially making the connection to anchor the platelet to the wound site.

Because von Willebrand factor is the linking factor to collagen, the lack of VWF causes easy bleeding in the skin and mucous membranes. This easy bleeding is why people with VWF deficiency notice that nosebleeds won’t clot easily – and menstrual bleeding can be excessive.

Von Willebrand disease classification:

There are three types of von Willebrand Disease:[ref]

VWD type 1 is the most common. It is defined by low levels (<50 IU/dL) of a functionally normal VWF, which is caused by inheriting a single VWF mutation.

VWD type 2 consists of the body creating the right amount of VWF, but the protein is malformed. There are four subtypes of VWD type 2:

- type 2A is defined by a decreased binding of VWF to platelet GPIb due to the size of the protein not being large enough.

- type 2M is characterized by the VWF not binding to platelets correctly.

- type 2B is defined by an increased binding of VWF to platelets — but at times when there is no injury. This increased binding causes the platelets to be removed by the body (thus decreasing platelets and VWF).

- type 2N VWD is defined by an impaired binding of VWF to FVIII.

VWD type 3 is defined by severe VWD, with undetectable (<1 IU/dL) plasma and platelet VWF levels. Two VWF mutations are needed for type 3 VWD.

People with type O blood naturally have lower levels of VWF. Thus, when testing for von Willebrand disease, the blood type needs to be considered.[ref]

Von Willebrand Genotype Report

There are quite a few mutations linked to von Willebrand disease. Below is just a partial list. Keep in mind, also, that 23andMe or AncestryDNA data are not guaranteed to be clinically accurate – meaning that false positives or false negatives are a possibility.

It is estimated that 1 – 3% of the population has von Willebrand disease.

Lifehacks

If you suspect you bleed longer than is normal, you should talk with your doctor. There are blood tests for bleeding times, and your doctor can likely help with any symptoms you have (nosebleeds, excessive menstrual bleeding, etc).

Medications such as desmopressin, a prescription medication, can increase von Willebrand factor. Other medication options may be available for situations such as delivery or surgery.[ref]

Related Articles and Genes

References:

Dwivedi, Rohini, and Vitor H. Pomin. “Marine Antithrombotics.” Marine Drugs, vol. 18, no. 10, Oct. 2020, p. 514. www.mdpi.com, https://doi.org/10.3390/md18100514.

Gill, JC, et al. “The Effect of ABO Blood Group on the Diagnosis of von Willebrand Disease.” Blood, vol. 69, no. 6, June 1987, pp. 1691–95. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V69.6.1691.1691.

Leebeek, Frank W. G., and Ferdows Atiq. “How I Manage Severe von Willebrand Disease.” British Journal of Haematology, vol. 187, no. 4, Nov. 2019, p. 418. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16186.

Veyradier, Agnès, et al. “A Laboratory Phenotype/Genotype Correlation of 1167 French Patients From 670 Families With von Willebrand Disease: A New Epidemiologic Picture.” Medicine, vol. 95, no. 11, Mar. 2016. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003038.