Key takeaways:

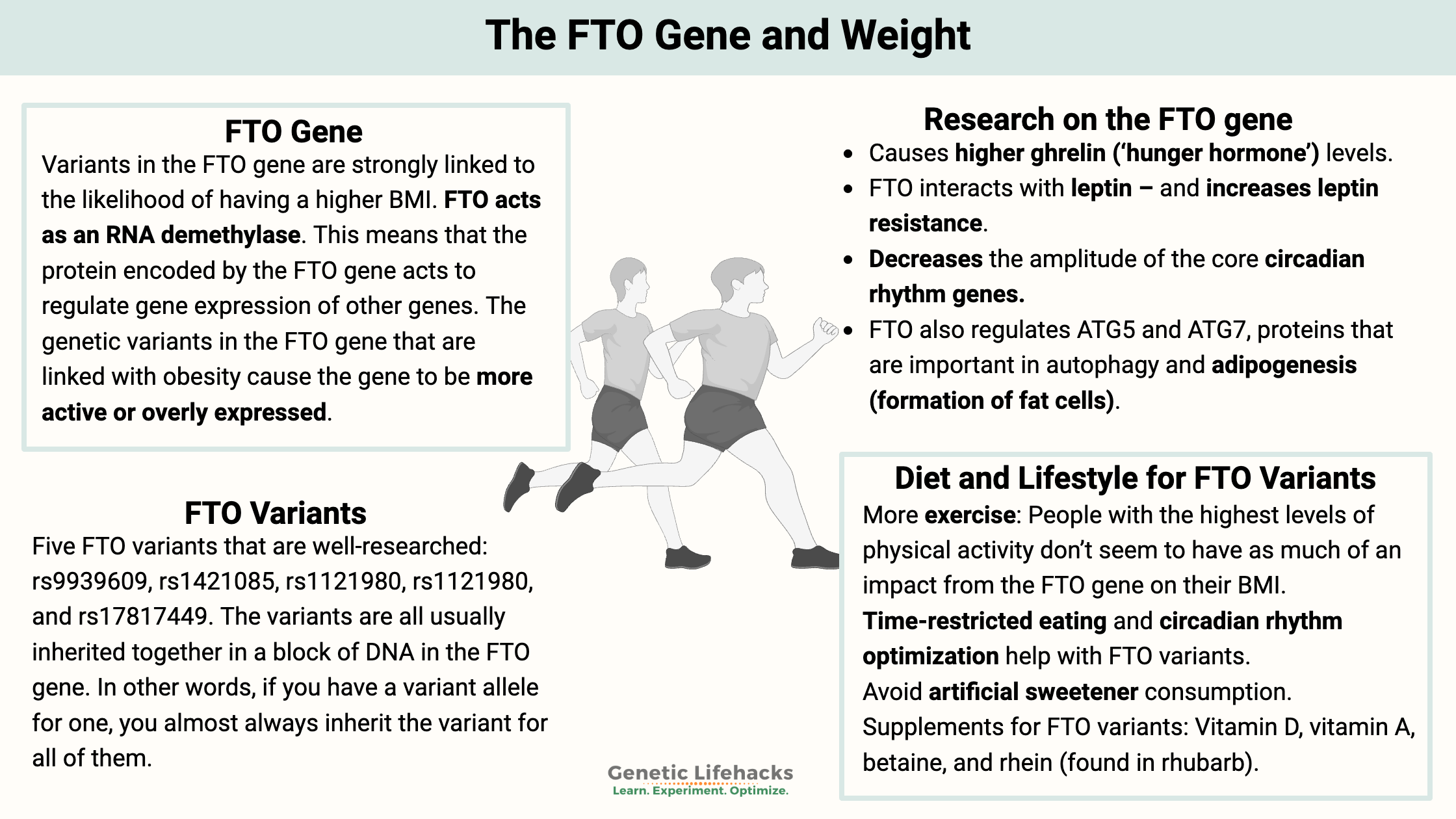

~Research shows that about 60% of obesity susceptibility is due to genetic differences, and the FTO gene is one of the key genes that has been consistently shown to impact weight.[ref]

~ The FTO gene is involved in turning on other genes related to metabolism and fat storage.

~ Genetic variants in FTO increase susceptibility to weighing more, but there are specific lifestyle factors that interact with the gene in obesity.

What is the FTO Gene?

The FTO gene was identified in 2007 in a genome-wide association study that looked at over 35,000 people to determine genes involved in obesity. Variants in the gene are strongly linked to the likelihood of having a higher BMI.[ref]

But… identifying the gene didn’t explain why it was so widely linked to higher BMI, as well as an increased risk of ADHD, depression, cancer, and dementia.

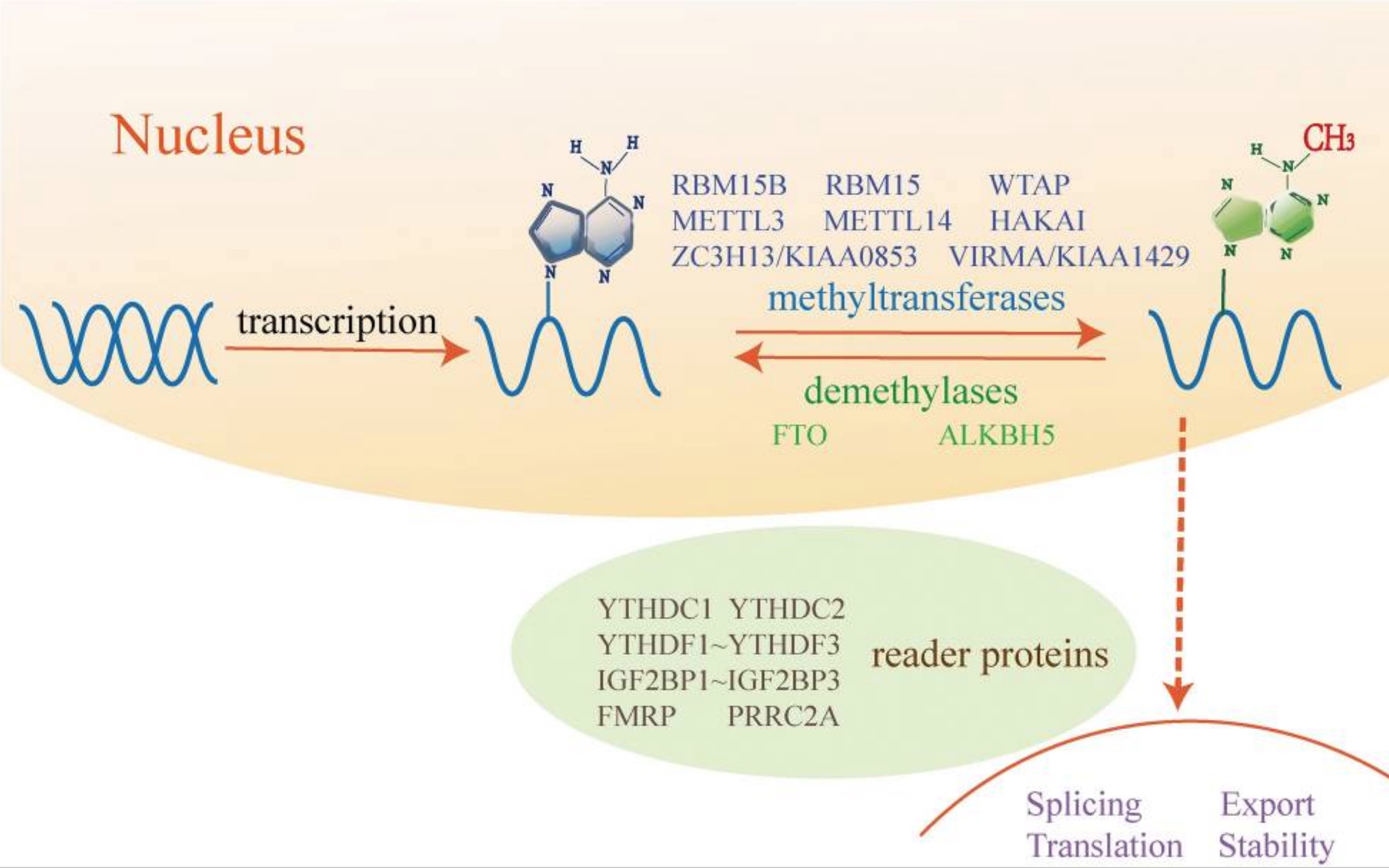

Recently, researchers discovered that FTO acts as an RNA demethylase. This means that the protein encoded by the FTO gene acts to regulate gene expression of other genes.[ref]

Quick background science:

I often explain that genes code for proteins, but that is an oversimplification that leaves out some key information. Genes are segments of DNA that are transcribed into mRNA (messenger RNA). The mRNA leaves the nucleus of the cell and is then translated by ribosomes into the amino acids that make up the protein.

Not all genes in the nuclear genome get translated into proteins, and the process of managing which proteins are made is called the regulation of gene expression.

There are several epigenetic ways that gene expression can be regulated in a cell:

- modification of the nuclear DNA, such as methylation, that turns off genes so that they aren’t transcribed into mRNA

– or – - post-translational regulation can prevent the transcribed mRNA from being translated into the protein

The FTO protein acts on specific mRNAs to control whether they are converted into their proteins. Specifically, FTO works like an eraser and takes away the markers, called m6A, on mRNA that stops it from being translated.

By erasing the methylation mark, the mRNA can be translated into the protein.

Keep in mind: The genetic variants in the FTO gene that are linked with obesity cause the gene to be more active or overly expressed.[ref] Thus, it is causing more of certain proteins to be created.

Let’s take a look at the research on the FTO gene – where it started and where it is today:

Overview of research on the FTO gene:

Prior to understanding the role of FTO as an RNA demethylase, a lot of research pointed towards the various pathways this gene touches upon.

- In 2013, a study found that those with variants in the FTO gene express more FTO, possibly altering ghrelin mRNA and causing higher ghrelin (‘hunger hormone’) levels.[ref]

Related article: Ghrelin Genes - A 2017 study points to FTO as important to the creation of muscle fiber and the creation of new mitochondria. Decreased FTO resulted in decreased muscle mass and decreased energy production by mitochondria.[ref]

- Animal models of increased FTO also show that it decreases the amplitude of the core circadian rhythm genes.[ref] Disruptions to the core circadian genes are tied to obesity in a lot of studies.

- A 2015 study showed that FTO polymorphisms disrupt ARID5B, which leads to increased IRX3 and IRX5. These two genes help to turn fat cells into white fat that stores lipids instead of the brown fat involved in thermogenesis. Other research points towards FTO interacting with mTOR, AMPK, and UCP2, which are central metabolic energy sensors.[ref]

- A mouse study showed that FTO interacts with leptin – and increases leptin resistance. The mouse study used a high-fat diet model to show leptin resistance.[ref]

- Children who carry the FTO variant associated with obesity are more likely to have greater energy consumption from fatty foods and also to have higher BMI. These children and adolescents also reported more ‘loss of control’ or binge eating episodes.[ref]

All of these initial studies make sense when you look at how the FTO protein regulates the formation of other proteins.

More recent studies elucidate the role of FTO and show that it is not only important in weight, but it also plays a regulatory role in many types of cancer. In cancer, FTO “regulates cancer stem cell function, and promotes the growth, self-renewal and metastasis of cancer cells.”[ref] (Perhaps this is one reason why obesity is a risk factor for cancer?)

FTO impacts a lot of genes:

To recap: FTO is a modifier and regulator of proteins, many of which have to do with growth — from embryonic development to the growth of fat cells or the growth of cancer cells.

Looking at the specific proteins that are impacted by FTO shows not only why it is associated with obesity, but perhaps explains why obesity is correlated with other diseases such as cancer, NAFLD, high blood pressure, heart disease, and more.[ref]

When it comes to metabolic regulation, FTO erases marks on the mRNA of FOXO1, G6PC, and DGAT2, increasing the expression of those proteins, which are all involved in glucose metabolism.[ref]

FTO also regulates ATG5 and ATG7, proteins that are important in autophagy and adipogenesis (formation of fat cells).[ref]

The FTO protein also regulates the expression of several important genes for heart health.[ref]

Trade-offs: FTO is necessary!

Please don’t get the idea that FTO is ‘bad’. The FTO protein is essential and shouldn’t be eliminated. In a mouse model, researchers have shown that deleting the FTO gene decreases weight — but it also activates the HPA axis and induces anxiety in the mice.[ref]

Instead of being completely negative, there are pros and cons of higher or lower levels of the FTO protein, with lifestyle factors coming into play.

FTO Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

What is the best diet for the FTO variants?

Studies on the FTO genetic variants are quite clear, linking them to a higher BMI.

However, research shows a lot of contradictions when it comes to the best diet.

Studies on diet and FTO show:

- A low-fat, low-calorie diet worked better for those carrying the risk variant.[ref]

- In another study, carriers of the risk variant had a 2.5x greater risk of obesity with high carb intake compared to those with the normal FTO version.[ref]

- However, the risk variant is linked to higher BMI only with high saturated fat intake.[ref]

- Thus, low fat, low carb, and low calorie… don’t eat anything?

Instead of having a clear picture of a single ‘best diet’ for the FTO variant, here are some specific nutrients and lifestyle factors that interact to impact weight gain…

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

MC4R- Growing Up Big Boned

There are several key players in our body’s regulation of hunger, satiety, and energy expenditure. Two pivotal hormones involved in our desire to eat are leptin and ghrelin. Within that leptin pathway, another key regulator of our body weight is MC4R.

Leptin Receptors

Do you wonder why other people don’t seem to struggle with wanting to eat more? Ever wished your body could just naturally know that it has had enough food — and turn off the desire to eat? You could be carrying a genetic variant in the leptin receptor gene, which is linked to not feeling as full or satisfied by your meal.

Ghrelin: The hunger Hormone

Learn how your genes impact your baseline ghrelin levels and how this impacts your weight.